Massachusetts leads the nation once again, this time with Phase II of health reform.

A 350-page bill filed five minutes before a legislative deadline for the year sets the first statewide target for health care spending in the U.S. Massachusetts would aim to hold health care cost increases to same rate as the state’s economy through 2017. A vote on the bill is expected Tuesday.

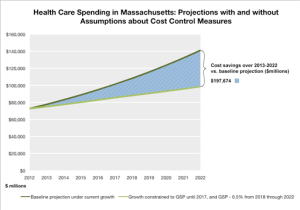

Specifically, health care costs could not rise faster than the Gross State Product from 2013 to 2017. The target would go lower (GSP minus 0.5) from 2018 to 2022. From 2023 on, it would return to even with GSP, but would be open to revision by the new oversight agency created in the bill. (The bill refers to the “potential” growth rate of the state’s GSP. The “potential” growth rate of the state’s GSP is, according to a helpful staffer, “an economic term used for reducing the fluctuations in business cycles to establish long-term average growth, smoothing out the highs and lows.”) The bill summary is here and the AP coverage here.

That agency will be under the governor’s Secretary of Administration and Finance. Legislators say it will look like the current Division of Health Care Finance and Policy (DHCFP), but with two separate missions: collecting unbiased data and establishing health care policy (setting ACO requirements, deciding whether the state has hit the GSP goal, tracking the move to global payments, for instance). The cost of getting this expanded agency up and running is expected to be $31 million, that’s $11 million more than the state spends on DHCFP now. The legislature plans to file a funding bill for the agency next year.

What to do about hospitals that use their market clout to demand higher prices was one of the most contentious issues in the bill. A House surcharge on hospitals that could not justify their higher price is gone. So is a plan to require separate hospital contracting (breaking up the powerful networks). Instead, this new House/Senate agreement would let DHCFP investigate hospitals suspected of anti-competitive pricing practices. DHCFP would refer findings that suggest a violation to the state Attorney General, but that office would not be required to follow-up on the findings.

There’s a wide range of reaction to this plan. Some health policy experts say it won’t lead to any change because the state can already conduct such investigations (but doesn’t). Some low-priced hospitals and consumer groups are relieved the state will have something in the bill that deals with market clout. And critics say this section makes hospitals vulnerable to investigations that have no merit.

Members of the committee that negotiated the final compromise bill say they will boost underpaid hospitals. A $225 million surcharge on insurers would be divided three ways with $135 million going into a fund for community hospitals. The bill also increases Medicaid reimbursements by 2 percent. “We have to make a commitment to our community hospitals,” says House Majority Leader Ron Mariano. “If we’re serious about providing low-cost, quality care, we have to shore up our community hospitals.”

The balance of the surcharge would be used to create a Prevention and Wellness Trust Fund ($60 million) and a fund to help small providers buy and start using electronic health records ($30 million). Critics, including Josh Archambault at the Pioneer Institute, point out that this surcharge will add to health costs.

There are dozens of other small and large items that we’ll dig in on in the coming days on WBUR’s Commonhealth blog as we look at this effort to control costs and improve care in Massachusetts. Many groups wanted to make sure their issue has a place in this legislation, which may become another template for national health care reform.

This story is part of a reporting partnership that includes WBUR, NPR and Kaiser Health News.