The accident happened 10 years ago when Chris Young was 35. He owned a salvage yard in Maui, Hawaii, and his employee had hoisted a junker on a machine called an excavator when the hydraulics gave out. The car fell on him from above his head, smashing his spine.

“He was crushed accordion-style,” says his wife Lesley.

The accident left Young with a condition known as “partial paraplegia.” He can’t walk and he needs a wheelchair, but he does have some sensation in his legs. Unfortunately for Young, that sensation is often excruciating pain.

Lesley Young testified that she has driven 100 miles to try to find a pharmacy that would fill painkiller prescriptions for her husband Chris. (Photo by Jessica Palombo/For KHN)

“It feels like electric shocks, like lightning bolts going down my legs. And when it gets down to the bottom, it feels like someone is driving a big metal spike up my legs,” says Young.

To control the pain, Young, who has since moved to Florida, needs high doses of narcotic painkillers, but he can’t always fill his doctor’s prescription. He is not alone. In what may be an unintended side effect of a crackdown on prescription drug abuse, Young and other legitimate chronic pain patients are having increasing trouble getting the medicine that allows them to function on a daily basis.

Young’s pharmacy runs out every month.

“They just do not have the medications because they have run out of their allocation within the first week,” he says. “It’s just that bad, where I know I am going to end up in the E.R. because of not having my medications. We don’t know what to do. We’ve tried everything.”

Young’s pharmacist is Bill Napier, who owns the small, independent Panama Pharmacy in Jacksonville. Napier says he can’t serve customers who legitimately need painkillers because the wholesalers who supply his store will no longer distribute the amount of medications he needs.

“I turn away sometimes 20 people a day,” says Napier.

Last year Napier says federal Drug Enforcement Administration agents visited him to discuss the narcotics he dispensed.

“They showed me a number, and they said that if I wasn’t closer to the state average, they would come back. So I got pretty close to the state average,” Napier says. He says he made the adjustment “based on no science, but knowing where the number needed to be. We had to dismiss some patients in order to get to that number.”

According to Napier, DEA agents took all of his opioid prescriptions and held on to them for seven months. Napier hired a lawyer and paid for criminal background checks on his patients taking narcotics to help him decide which ones to drop.

“We’re being asked to act as quasi-law enforcement people to ration medications,” says Napier. “I have not had training in the rationing of medications.”

Until a few years ago, Florida was considered the epicenter for the trafficking of illegal prescription narcotics. The DEA and local law enforcement shut down more than 250 so-called “pill mills” — clinics where doctors could sell narcotics directly to people for cash. Now Florida doctors can no longer dispense narcotics directly to patients. Wholesalers, who paid to settle claims for failing to report suspicious orders of drugs, now limit the amount they sell to pharmacies, Napier says.

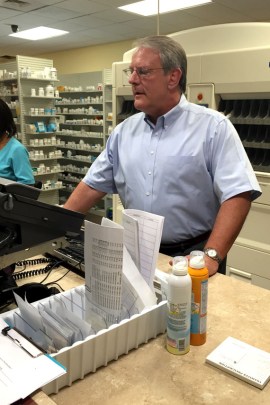

Pharmacist Bill Napier hired a lawyer to do criminal background checks on his patients who take painkillers to help him decide who to dismiss. (Photo by Jessica Palombo/For KHN)

Jack Riley, who is acting deputy administrator of the DEA, credits a decline in opioid overdose deaths in Florida with an upsurge in law enforcement activity. The problem of addiction and the drug trade is dire, he says.

“A hundred and twenty people a day die of drug abuse in this country,” Riley said. “If that doesn’t get your attention, I don’t think anything can.”

Riley also says law enforcement efforts cannot be blamed for any claim of rationing of painkillers.

“I’m not a doctor. We do not practice medicine. We’re not pharmacists. We obviously don’t get involved in that,” said Riley. “What we do do is make sure the people that have the licenses are as educated as possible as to what we’re seeing, and that they can make informed decisions as they do dispense.”

Doctors, too, say DEA enforcement actions have made it harder for them to prescribe narcotics. Last year, hydrocodone products, such as Vicodin, were changed to Schedule II status, meaning they have a high potential for abuse and cannot be prescribed in large quantities.

“What we’ve seen is dramatic reductions in our ability to provide appropriate care for our patients in pain,” says Dr. R. Sean Morrison, director of the palliative care program at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York.

Morrison’s patient Ora Chaikin has been taking high levels of narcotics for years to control her pain. She has had multiple surgeries because her bones and ligaments disintegrate, a problem caused by rheumatoid arthritis and other autoimmune diseases. But Chaikin, who lives in Riverdale, N.Y., says her mail order pharmacy, CVS/caremark, has been denying her medications.

“Every month there’s a reason they won’t give me my medication,” says Chaikin. “Sometimes it’s ‘Well, why are you taking this dose?’ ‘My doctor prescribed it.’ ‘Well, why did your doctor prescribe so much?’ ‘Ask my doctor,’” she recounts. “That’s the dose that works for me and you’re made to feel like a drug addict.”

The DEA investigated both CVS and Walgreens, and both pharmacy chains settled civil suits in 2013 for record-keeping violations of the Controlled Substances Act. Walgreens paid an $80 million civil penalty, and CVS paid an $11 million penalty.

Riley, of the DEA, says it would be wrong to draw a line between these actions and problems like those Chaikin is experiencing. “If there is a chilling effect, it’s clearly not at our direction,” Riley said. “We’re simply enforcing the law, taking bad people off the street and really trying to interrupt the supply of illegal prescriptions.”

In a statement, CVS/caremark said that the dosage of pain medication prescribed to Chaikin “exceeded the recommended manufacturer dosing.” It also said that she “continued to receive her controlled substance prescriptions from CVS/caremark without interruption.”

CVS/caremark said it has a legal obligation to make sure controlled substance prescriptions are for legitimate ailments and “that patients are receiving safe medication therapy, including appropriate dosing.”

Ora Chaikin’s wife, Roseanne Leipzig, who is a geriatrician and palliative care physician, says when it comes to narcotics, there is nothing in medical literature that says a dose is too high.

“There is no maximum dose for narcotics,” she says. “It’s the dose you need to take care of the pain.”

The Florida Board of Pharmacy, which is responsible for licensing pharmacists and educating them on safe practice, has heard enough complaints from pain patients that it is addressing the issue in public meetings. In June, Lesley Young testified before the board on behalf of her husband. She said she has driven more than 100 miles trying to find a pharmacy that would fill her husband’s prescriptions for painkillers.

“I’ve had to do the pharmacy crawl like many of us here,” Lesley told the board. “I’ve been the one who had to go in and beg, crying, with stacks of his medical records, with stacks of imaging, only to get turned away, often rudely, saying ‘We don’t deal with those kinds of patients.’”

The next Florida Board of Pharmacy hearing is set for Monday. A representative of the DEA has been invited to attend.

This story was produced in a collaboration between NPR’s Here & Now and Kaiser Health News.