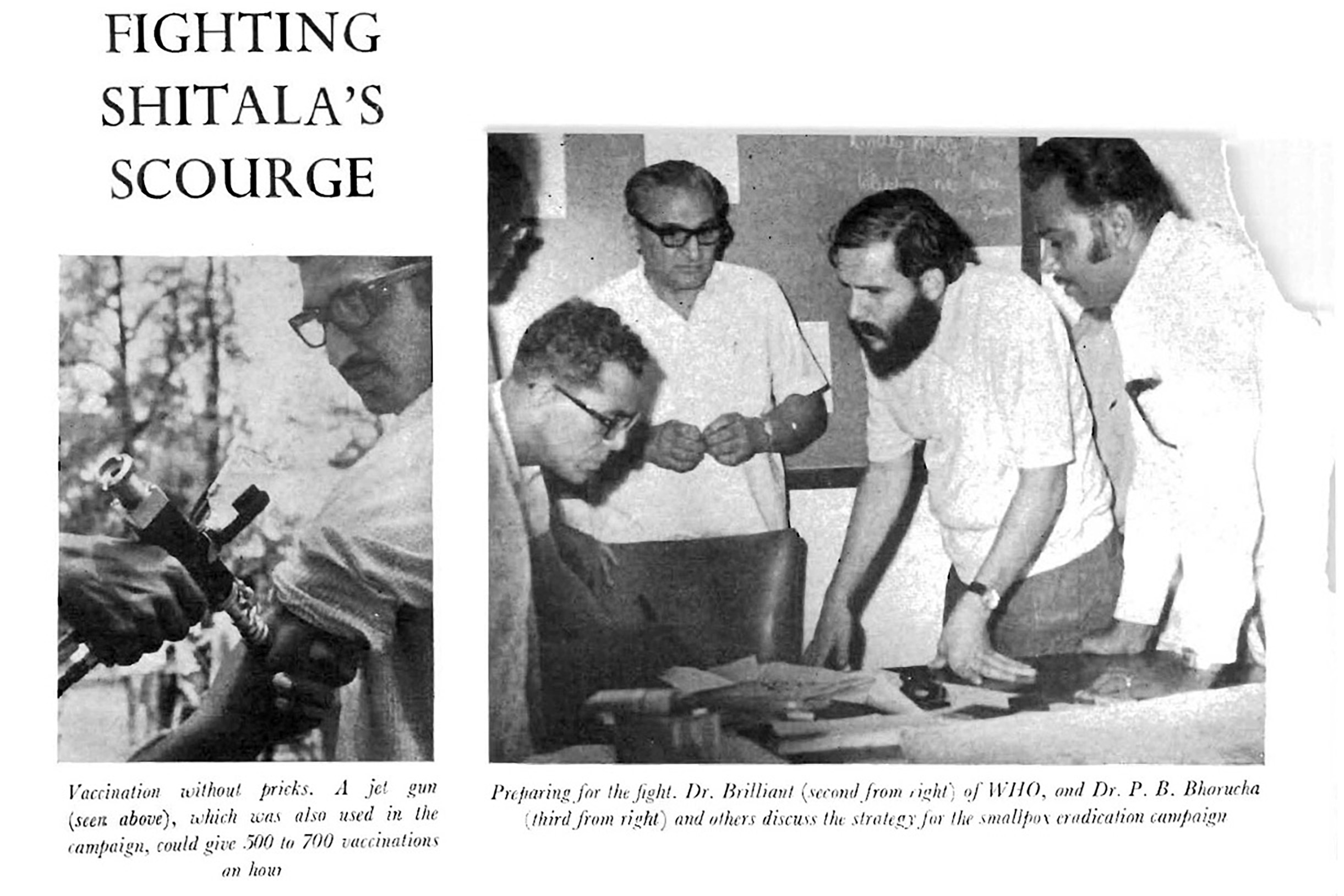

In spring 1974, over a dozen smallpox outbreaks sprang up throughout the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh. Determined to find the source of the cases, American smallpox eradication worker Larry Brilliant and a local partner, Zaffar Hussain, launched an investigation.

The answer: Each outbreak could be traced back to Tatanagar, a city run by one of India’s largest corporations, the Tata Group.

When Brilliant arrived at the Tatanagar Railway Station, he was horrified by what he saw: people with active cases of smallpox purchasing train tickets. The virus was spreading out of control.

Brilliant knew that to stop the outbreak at its source, he would need the support of the company that ran the city. But he wasn’t optimistic the Tata Group would help.

Still, he had to try. So, Brilliant tracked down a Tata executive and knocked on his door in the middle of the night.

Brilliant’s message: “Your company is sending death all over the world. You’re the greatest exporter of smallpox in history.”

Much to his surprise, the leaders of Tata listened.

Episode 5 of “Eradicating Smallpox” explores the unique partnership between the Tata Group and the campaign to end the virus. This collaboration between the private and public sector, domestic and international, proved vital in the fight to eliminate smallpox.

To conclude the episode, host Céline Gounder speaks with NBA commissioner Adam Silver and virologist David Ho about the basketball league’s unique response to covid-19 — “the bubble” — and the essential role businesses can play in public health. “We need everyone involved,” Ho said, “from government, to academia, to the private sector.”

The Host:

In Conversation With Céline Gounder:

Voices From the Episode:

Podcast Transcript

Epidemic: “Eradicating Smallpox”

Season 2, Episode 5: The Tata Way

Air date: Sept. 26, 2023

Editor’s note: If you are able, we encourage you to listen to the audio of “Epidemic,” which includes emotion and emphasis not found in the transcript. This transcript, generated using transcription software, has been edited for style and clarity. Please use the transcript as a tool but check the corresponding audio before quoting the podcast.

TRANSCRIPT

Céline Gounder: To help us tell the next chapter of the smallpox eradication history, we went to someone who’s lived a lot of lives. A civil rights activist. A Deadhead. A disciple of guru Neem Karoli Baba. A tech entrepreneur. And … an epidemiologist.

Larry Brilliant: Hi, I’m Larry Brilliant. and I had the great honor of working on the WHO smallpox eradication program.

[Light music begins playing softly]

Céline Gounder: Larry was looking for his place in the world as a young man. It took him all over the United States. And beyond …

Larry Brilliant: Hoping that I would find something that was better than capitalism … that helped the poorest and most vulnerable communities.

Céline Gounder: That calling eventually led him to India — and the campaign to end smallpox.

Larry Brilliant: In those days, the world really wanted a victory in global health. So, we wanted, as a world, to eradicate smallpox.

Céline Gounder: At one point, when government reports suggested that smallpox was getting worse, not better, a young Larry still believed his team could beat the disease.

Many said that version of him from 50 years ago was perhaps brilliant — but also impatient, and a bit brash.

So, when one honcho at the World Health Organization headquarters in Geneva said he would eat a truck tire if they ever managed to get rid of smallpox, Larry and his boss, a Swiss-French epidemiologist named Nicole Grasset, took the bet.

A few years later, after the WHO declared victory over smallpox in 1980, Nicole and Larry mailed the skeptic a tire — all the way from India! — with a little note saying:

Larry Brilliant: “As agreed, here is the Land Rover tire. Please inform us — the bouquet and the texture — and should you need ketchup or mustard or any other condiments, we would be happy to add them to this.”

Céline Gounder: What happened to the tire?

Larry Brilliant: We never know. He never responded. [laughs]

[Music fades out]

Céline Gounder: Larry’s laughing now, but there were lots of dark days before that win. 1974 was a particularly tough year for the eradication program.

And Larry was about to find himself in the middle of one of the worst smallpox outbreaks anyone could remember.

To stop it, he would have to become a detective and follow the clues to the source of the surge. And once he solved that mystery, he’d need to stand up to one of the most powerful companies in India.

I’m Dr. Céline Gounder, and this is “Epidemic.”

[Epidemic theme music plays]

Céline Gounder: The year started off well. The new search-and-containment strategy was working.

It was working so well that Larry and his team were convinced they had eliminated smallpox in their area.

The reports from three statewide searches had come back. Not a single case had been found.

Soon, they’d be ready to declare the region free of smallpox.

[Suspenseful music begins playing]

Larry Brilliant: And we did one more search, and we found 15 villages that were infected with smallpox.

Céline Gounder: That last search was supposed to be a victory lap. Now, the race had started all over again.

Larry dispatched teams to find out where the cases were coming from.

Larry Brilliant: No one had any idea what it was.

Céline Gounder: Then finally … a break.

Larry Brilliant: We went into a little village, and we were able to find that the first case was a young man in his 20s, and he had gone someplace for work and came back with smallpox.

Céline Gounder: Larry asked the rest of the team if they had found anything similar.

Larry Brilliant: All of them came back “yes.”

Céline Gounder: They found a pattern — a clue. All the cases originated with a young person who had been away from home looking for work.

But where had they gone? If Larry’s team was going to stop the outbreak, they had to figure out where the workers got infected.

When the first clue surfaced, Larry was with another smallpox campaigner. A local partner, Zaffar Hussain …

Larry Brilliant: … who knew more about smallpox than I did. He knew more about smallpox than anybody.

Céline Gounder: Larry and Zaffar were running out of options. So, Zaffar tried one last thing.

Larry Brilliant: When they were preparing this boy’s body for cremation, Zaffar asked in the humblest way for permission to go through his pockets. And he did, and he found in the boy’s pockets a railway ticket from the Tatanagar Railway Station.

Céline Gounder: Tatanagar.

They had found the source of the outbreak.

[Suspenseful music fades out]

[Ambient sounds and an announcement from the Tatanagar Railway Station play]

Céline Gounder: In the summer of 2022, I followed Larry’s journey to the Tatanagar. The city — also known as Jamshedpur — is in the eastern end of India. The train station is a knot of railroad tracks. The platforms are full of vendors selling food. You have to dodge bales of cargo on the way to the train.

Tatanagar’s name comes from the family … and the company … that dominates the area: Tata.

Larry Brilliant: It was known as the “Pittsburgh of India.”

[Upbeat music begins playing]

Céline Gounder: Steel. Iron. Locomotives. Tata was a household name. It still is. The conglomerate’s dozens of businesses span heavy industry and telecommunications to aerospace.

Ever ride in a Land Rover? Tata.

A Jaguar? Tata.

Fly Air India? That’s part of the Tata Group, too.

In the ’70s, people looking for work in Tata factories took trains to Tatanagar. Thousands and thousands of people passed through the train station every day.

For many, the city was a vision of India’s future.

[Music fades out]

Larry Brilliant: So, when you thought of Tatanagar, when you thought of Tatas, in those days, you thought of wealth, power, modernity, cleanliness, all of those things.

Céline Gounder: But the scene Larry and Zaffar saw when they arrived was very different.

They found a station boiling with smallpox. Bodies wrapped in cloth were stacked like cords of wood.

[Somber music begins playing softly]

Céline Gounder: Some small enough to be children.

As the crowd swirled around Larry, an older man about to buy a train ticket caught his eye.

Larry Brilliant: He had given the couple of rupees, and he had just gotten the ticket and his hand was filled with pockmarks. And you could just imagine that that man’s about to get on a train and go back home to die in his home village. And that will be another outbreak that will be started.

Céline Gounder: Larry was overwhelmed.

Larry Brilliant: You gotta understand that the feeling of powerlessness, anger, anger at the Tatas for letting this happen, anger at … God?

[Music fades out]

Larry Brilliant: I said to Zaffar, you know, what do we do?

And he said, we’ve got to find the head of the Tatas.

Céline Gounder: At the time, that meant Russi Mody, who was the managing director of Tata Steel.

Larry and Zaffar got the address — a home in a suburb outside the city.

As they drove in the dark, Larry was thinking about the person he was about to confront.

Larry Brilliant: So I, I had a terrible, fear that the Tatas would turn a deaf ear or already knew about it.

Céline Gounder: Tatanagar was basically a company town. Tata ran the city. It was in charge of lots of things that governments would otherwise do.

Larry Brilliant: And I had this image of a company that just didn’t care.

[Instrumental music begins playing]

Céline Gounder: It was nearly midnight by the time they arrived at the home of the Tata Steel executive.

Larry Brilliant: And I, I ran up to the front door, with Zaffar pulling me back: “Don’t go, don’t go.”

And I pounded on the door. And the door opened.

Céline Gounder: An attendant answered the door. He was not impressed with Larry’s WHO credentials. The attendant tried to turn them away.

Larry Brilliant: And I kind of pushed my way in, and one of these huge Tibetan Mastiff dogs that they had grabbed my hand. And wouldn’t let me go.

Céline Gounder: By now, the ruckus was too much to ignore. The company managing director, Russi Mody, got up and came to the door.

Larry Brilliant: “Who the hell are you? What are you doing here at my house at midnight?” And while this dog still had my arm in his mouth, I told Russi, I said, “You know, your company is sending death all over the world. You’re the greatest exporter of smallpox in history.”

Céline Gounder: That got Russi’s attention. He ordered his dog to let go of Larry’s hand.

[Music fades out]

Larry Brilliant: And he’d been trained not to bite off the hand, thank God.

Céline Gounder: Russi invited Larry and Zaffar in.

When they all sat down together at the dinner table, Larry explained the situation: mysterious smallpox cases popping up all over India. The train ticket in the man’s pocket that led them to Tatanagar. The chaos they found at the train station.

Russi said he had no idea what had been going on.

But Larry had his doubts.

Larry Brilliant: It seems improbable that the head of the Tatas wouldn’t know about it, but I actually think they did not know about it. It wasn’t that they were willfully ignorant, they just didn’t know about it — that that reporting relationship didn’t exist.

Céline Gounder: Russi asked what could be done. Larry made up a number. Something close to asking for half a million dollars, he estimates. It would cover 4×4 trucks, equipment, and personnel to contain the outbreak.

But, as influential as Russi Mody was, this was a big ask.

Larry Brilliant: So he called up Bombay and spoke to Mr. Tata, J.R.D. Tata.

Céline Gounder: Jehangir Ratanji Dadabhoy Tata — or J.R.D. — was the “Tata” in Tata Industries.

[Sparse percussive music begins playing]

Larry Brilliant: He was probably a combination of Steve Jobs and, I don’t know, the CEO of GM when GM was a big deal.

Céline Gounder: J.R.D. ran his business empire according to how he interpreted the values set out by its founder, Jamsetji Tata.

His speeches and public statements suggest that Jamsetji believed that his company should serve a higher purpose.

The well-being of the community — and the nation — was supposed to be a driving force behind the company. Not just profits. That approach to business was called “the Tata Way.”

But Larry wondered: Would this tycoon really help?

Larry and Russi explained what was needed.

And J.R.D. said yes.

[Music fades out]

Larry Brilliant: And by 2 o’clock that afternoon, I had 200 jeeps, and all the different Tata companies, Tata Iron and Steel, […] Tata Locomotive, all their CEOs, and most of their executives showed up at this one site that became the smallpox office.

Céline Gounder: Larry took that “yes” he got from Tata and ran with it.

Larry Brilliant: I decided — without talking to anybody, again, youthful enthusiasm — I had decided that what I was going to do is to quarantine the city.

Céline Gounder: This was no small undertaking. More than 600,000 people were living in the area. That’s like trying to quarantine Washington, D.C.

The trains stopped running.

The buses stopped running.

The only ticket in or out was proof you’d been vaccinated: a smallpox vaccination scar.

Larry Brilliant: And bear in mind, I hadn’t asked permission to do this, which is, you know, clearly a failing on my part, but it was an emergency.

Céline Gounder: Not everyone thought it was an emergency. Larry’s decision was controversial.

When a member of Parliament got caught up in the quarantine and was forced to get vaccinated, there was a big uproar.

People accused the WHO of overstepping its authority. Friends of Larry’s in the Indian government told him the pushback almost got him deported. And maybe even risked getting the entire WHO program kicked out of the country.

But Larry had made powerful friends in India’s health system. And with the Tatas.

[Grandiose music begins playing]

Larry Brilliant: The Tatas at every, every stage of that, lobbied for me to be able to stay.

Céline Gounder: Tata leaders helped keep Larry out of trouble. And they made sure their own factories followed his rules, too.

Larry Brilliant: They literally closed down the assembly lines for locomotives and they stopped making iron and steel. They stopped the coal mine, and all of their workers came to work on this for almost six months.

Céline Gounder: Local government, businesses, and community groups all stepped up. Even a flying club offered to drop leaflets from the air so people would know how to identify and report any smallpox cases.

Two months later, the smallpox outbreak was contained.

Larry Brilliant: I’d never seen anything work that well. None of us had.

There’s no question that they put public health ahead of profits because they closed down and diverted all their managers to helping smallpox be eradicated.

Now, you could argue that they would have lost more had they gotten branded with the reintroduction of smallpox in the world; you could argue that it was enlightened self-interest, but it seemed to me much more than that.

Céline Gounder: The Tata Way, perhaps.

[Music fades out]

Céline Gounder: Working with the Tatas made a big impression on Larry.

Larry Brilliant: Watching the way you could combine public health with its moral compass, with the resources and management skills of Tatas.

That was quite something.

And the Tatas were the first I’d ever seen like that. And as a young person, still formulating my own worldview, it changed me, of course, forever.

[Reflective music begins playing]

Céline Gounder: J.R.D. Tata’s support of the smallpox eradication campaign came at a critical time. But smallpox wasn’t the only public health campaign the tycoon backed.

He also used his power and money to further population control in India.

J.R.D. Tata: As the standard of living of the people increase and they want their children educated, et cetera, it’ll be here, it’ll happen here, but too late.

Céline Gounder: That’s a clip of J.R.D. on the Indian television program “Conversations” in 1987 talking about the need to curb India’s birth rate.

J.R.D. Tata: […] and therefore one must find some ways of accelerating the process.

Céline Gounder: J.R.D. used his business to make that vision a reality.

In the 1970s, the Indian government was offering its citizens cash payments if they would get sterilized as part of its population control efforts.

J.R.D. doubled it for his employees and their spouses.

From 1975 to 1976, Tata Steel claimed to have carried out 20,000 sterilizations.

[Music fades out]

Céline Gounder: That’s troubling for me as a public health professional. Offers of cash in a very poor country can be coercive. And it makes the legacy of the “Tata Way” complicated.

The company’s far-reaching influence and philanthropy also created the university where my own father studied. An opportunity that gave him a career in the United States, and ultimately shaped my life and career.

[Bouncy music beings playing]

Céline Gounder: The resources of private enterprise — they can be marshaled for good and bad alike.

We saw that at the beginning of the covid-19 pandemic. Businesses weren’t always on the same side as public health. But they can also be powerful allies.

Adam Silver: The partnerships are critically important with public health officials, with research institutions, and, and at the same time, the sort of magic of free enterprise can be extraordinarily helpful.

Céline Gounder: When we come back, we’ll speak with NBA Commissioner Adam Silver and virologist David Ho about the basketball league’s response to covid and its investment in public health.

That’s after the break.

[Music fades out]

Dan Weissmann: Hey there! “An Arm and a Leg” is a show about why health care costs so freaking much. And what we can maybe do about it.

[Upbeat music begins playing]

Dan Weissmann: I’m Dan Weissmann. I’m a reporter and I like a challenge. So, my job on this show is to take one of the most enraging, terrifying, depressing parts of American life and bring you a show that’s entertaining, empowering, and useful.

“An Arm and a Leg” Guest 1: Where there’s money, there’ll be scams.

Dan Weissmann: I’m not gonna lie … we can’t win ‘em all. But it turns out, we don’t have to lose them all either.

“An Arm and a Leg” Guest 2: I was so determined. Like, I was not going to go through all of this for nothing.

“An Arm and a Leg” Guest 3: You have to be willing to tell people in authority sometimes, that you believe they’re wrong.

“An Arm and a Leg” Guest 4: I’m not scared of these fools.

“An Arm and a Leg” Guest 5: That’s when politicians really started getting involved and they passed the law.

“An Arm and a Leg” Guest 6: It’s like reading a postscript in a Dickens novel almost. Like, “Hey look! Now we can’t chain children to factory machines.” Like, “What? Wait, what? That was legal before?”

[Music fades out]

Dan Weissmann: You can catch “An Arm and a Leg” at armandalegshow.com or wherever you get podcasts.

Céline Gounder: On March 11, 2020, two basketball teams were getting ready to start a game in Oklahoma City. The arena was packed. Players from the Utah Jazz and the Oklahoma City Thunder were warmed up, and nothing seemed out of the ordinary. But then the coaches and the referees had a meeting, and everyone on the court walked back to their locker rooms.

ESPN and NPR captured what happened next.

ESPN Clip: The fans here in the arena don’t know what’s going on. We don’t know what’s going on. And so, as soon as we get any kind of information, we will certainly pass it along. The game tonight has been postponed. You are all safe.

NPR Clip: The NBA has suspended its entire season. That decision came last night after a player with the Utah Jazz tested positive for covid-19.

Céline Gounder: I don’t think I’m alone in saying that was the moment a lot of people realized that the covid pandemic was real and would upend our lives. For NBA Commissioner Adam Silver, the challenge also presented an opportunity for the league to form business partnerships and model a path forward.

To learn more, I called up Silver and Dr. David Ho, a professor of medicine at Columbia University, who has advised the NBA on health issues since the 1990s, when he served as the doctor for NBA superstar Magic Johnson when Johnson was diagnosed with HIV.

David, thinking back to early 2020, how were you assisting Adam and the rest of the NBA in terms of research and in terms of their decision-making?

David Ho: Adam and, and the league put together a team and there were numerous discussions prior to the first case. And so there was a sort of a … anticipation that the virus would get to the U.S. and, and, and, you know, hit everyone at some point. And remember, by third week of January, China already locked down Wuhan city. So that really taught us how severe this outbreak might be.

Céline Gounder: The shutdown could not have come at a worse time for the NBA. The regular season was winding down and they were about to begin the playoffs to crown an NBA champion. Those playoffs generate a lot of money. But then, in the summer of 2020, the NBA came out with a bold idea to restart their season — at Disney World. It’s been called “the Bubble.”

Adam, from your perspective, how, how would you explain to maybe another, uh, CEO of a company, how you set up the Bubble and what this was?

Adam Silver: It was a partnership with Disney. Uh, we were fortunate that they had available this physical campus, several hundred acres, as part of Disney World that was otherwise completely shut down because of the pandemic.

So they had the hotel rooms, they had existing courts, they had facilities for training. I mean, a lot of it we needed to modify and bring in significant other equipment. But the fundamentals were there already. And at the peak of the so-called Bubble, we had about 1, 500 people there — that included players, coaches, team, and league personnel.

Celine Gounder: Now leading up to the return to play, the NBA and the Players Association helped finance a saliva-based covid test with Yale, which would later be called SalivaDirect, and they got emergency authorization from the FDA for this. NBA players even helped in the trials. Adam, why did the NBA support this initiative?

Adam Silver: Frankly, Dr. Gounder, because we were desperate for a methodology under which we could return to play. And for me, this was a function of the private sector, looking for an opportunity to partner with major research institutions — as you said, in this case, it was the Yale School of Public Health. But, you know, finding a way where we would be in position to do rapid testing on a large-scale basis.

And certainly, there were a lot of nervous people, and there were never any guarantees that we would have zero cases, which we turned out to have down in the Bubble. But, um, you know, it seemed like a wise decision at the time.

Céline Gounder: David, how can some of those innovations that were developed to restart the season be made to reach the broader public?

David Ho: Yeah, I think the public is aware of the success of the NBA Bubble, but it’s probably not aware of the fact that NBA published 10 scientific papers because of their covid response. And, for example, with the daily testing after the Bubble, the infected individuals were captured and tested every day. So we have a trajectory for the viral load of the infected people.

That’s just one example. And another would be correlates protection. NBA had one point drawn blood and we were able to measure antibodies and then NBA follow everyone and knew which, which person got infected and which ones did not. And from that, you could discern a certain antibody level was protective.

These type of contributions are, are not well known to the public, but it’s amazing. Uh, it was more successful than many academic groups on the scientific front.

Céline Gounder: Adam, what would you change about the NBA’s response to covid, if anything?

Adam Silver: If we had to do it again, I would have focused a bit more on mental wellness issues around our players living in that environment over long periods of time.

We were very restrictive in terms of who could live in the Bubble, meaning initially there were no family members permitted. And I think that the impact of the isolation was fairly profound. So we learned as we went that given the importance of the mental health issues for our players and for others in the community, on balance, we were better off allowing more family members in.

Celine Gounder: In the next public health crisis, how do you think that the private sector should respond and partner in solving?

David Ho: For a pandemic, we need everyone involved, you know, from government to academia to the private sector. Government alone can’t address this and nor could medical community alone. So, it has to be a partnership.

[“Epidemic” theme music begins playing]

Céline Gounder: Next time on “Epidemic” …

Sanjoy Bhattacharya: There are tales of how villages would empty when rumors would spread that these teams were coming ostensibly to vaccinate, but maybe really to sterilize. I mean, bodies still remember what was done to them.

Céline Gounder: “Eradicating Smallpox,” our latest season of “Epidemic,” is a co-production of KFF Health News and Just Human Productions.

Additional support provided by the Sloan Foundation.

This episode was produced by Zach Dyer, Taylor Cook, Bram Sable-Smith, and me.

Swagata Yadavar was our translator and local reporting partner in India.

Our managing editor is Taunya English.

Oona Tempest is our graphics and photo editor.

The show was engineered by Justin Gerrish.

We had extra editing help from Simone Popperl.

Music in this episode is from the Blue Dot Sessions and Soundstripe.

News clips from ESPN and NPR.

We’re powered and distributed by Simplecast.

If you enjoyed the show, please tell a friend. And leave us a review on Apple Podcasts. It helps more people find the show.

Follow KFF Health News on X (formerly known as Twitter), Instagram, and TikTok.

And find me on X @celinegounder. On our socials, there’s more about the ideas we’re exploring on the podcasts.

And subscribe to our newsletters at kffhealthnews.org so you’ll never miss what’s new and important in American health care, health policy, and public health news.

I’m Dr. Céline Gounder. Thanks for listening to “Epidemic.”

[“Epidemic” theme fades out]

Credits

Additional Newsroom Support

Lydia Zuraw, digital producer

Tarena Lofton, audience engagement producer

Hannah Norman, visual producer and visual reporter

Simone Popperl, broadcast editor

Chaseedaw Giles, social media manager

Mary Agnes Carey, partnerships editor

Damon Darlin, executive editor

Terry Byrne, copy chief

Gabe Brison-Trezise, deputy copy chief

Chris Lee, senior communications officer

Additional Reporting Support

Swagata Yadavar, translator and local reporting partner in India

Redwan Ahmed, translator and local reporting partner in Bangladesh

“Epidemic” is a co-production of KFF Health News and Just Human Productions.

To hear other KFF Health News podcasts, click here. Subscribe to “Epidemic” on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google, Pocket Casts, or wherever you listen to podcasts.