In the growing world of retail health care, where you can get your flu shots down the aisle from your Fritos, insurers like Florida Blue are jumping into the business — with a South Florida spin.

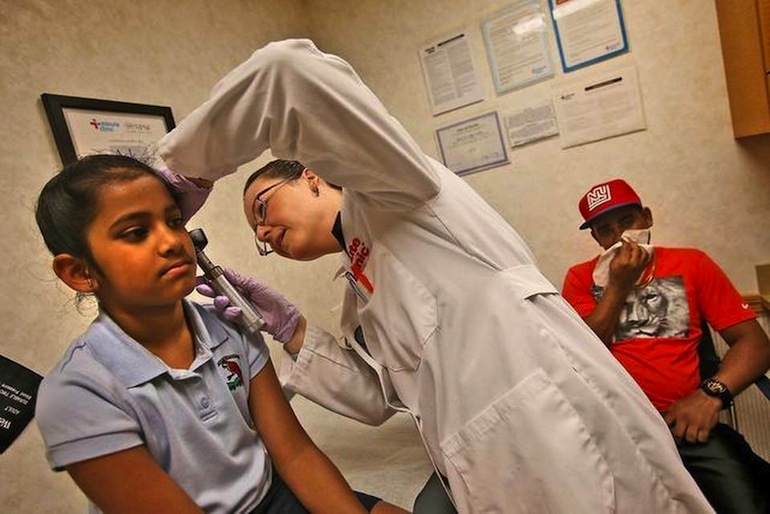

Clinic Practice Manager Lilia Pino examines 6-year-old Ashera Samad in Kendall, Florida (Photo by Patrick Farrell/Miami Herald Staff).

In September, the insurer will debut three “integrated care” facilities designed to cater to South and Central American populations by offering primary care, specialty services, labs and diagnostics under one roof — a model that is common in Latin America.

The move reflects a consumer-focused style of administering care that has grown in popularity since the implementation of the Affordable Care Act. Now, more consumers are insured than ever before — 1.6 million Floridians enrolled in the marketplace in 2015 alone — many also leaving their employer’s coverage to shop for individual plans on the exchange.

The result: Consumers want more transparency and affordability, with the option to price compare and get speedy service.

Enter retail health care — the Expedia model for medical services — in which clinics post their prices and allow consumers to choose which services they want, where and when. No making appointments. No waiting for doctors. No ambiguous price schemes.

Krista Bowers, managing director for Miami-based health care consulting firm BDC Advisors, said that out-of-pocket costs and high deductibles, which are common in the most popular marketplace plans, have made consumers more price conscious. And that has fueled the growth of a retail-centric clinic model.

“They have more skin in the game,” Bowers said. “The more money you have at stake, the more you’re willing to shop.”

People don’t want to wait months to get an appointment with a primary care provider, Bowers said, nor do they want to guess how much a service will cost.

“The traditional kind of physician office, because of its inability to be super effective and because of its inability to offer convenient costs, is being attacked,” Bowers said.

In the last decade, more retailers have joined the charge, led by CVS, which opened its MinuteClinics in 2006 offering anything from flu shots to physicals. Now there are more than 960 MinuteClinics nationwide. About 300 have opened since 2012 alone, including 33 in Florida.

Andrew Sussman, president of the MinuteClinics, said that a primary care doctor shortage, an aging population and an epidemic of chronic disease has powered the retail health care option.

According to a report released this month by the Association of American Medical Colleges, there will be a predicted shortage of 46,100 to 90,400 physicians by 2025.

This is where the retail clinics will fill the void, experts said, by not replacing the primary care physician, but rather adding another avenue for care.

Patrick Carroll, chief medical officer of the Walgreens Health care clinics and a family practice physician, said he was managing 3,000 patients at his practice, many of whom he could not schedule for same-day appointments or on nights and weekends.

More than a third of Walgreens patients and about half of CVS patients visit the clinics after work hours or on weekends, the companies said. The clinics are frequently staffed by nurse practitioners, who are expected to increasingly become patients’ first stop for less-complicated medical issues.

But Susan Lynch, CEO of the Florida Association of Nurse Practitioners, said this may become a problem in Florida where nurse practitioners are more limited in practice than in any other state.

Florida is the only state that does not allow nurse practitioners to become licensed to prescribe medications such as cough medicine with codeine and some pain killers, Lynch said. Florida nurse practitioners must also be supervised by a physician. A Florida Senate bill this year proposes expanding their abilities to prescribe drugs.

In South Florida, Florida Blue is leading the charge for more innovation in retail health care by tapping into technology and the area’s cultural ties.

At Florida Blue’s storefront across from The Falls mall, a futuristic white and blue pod called HealthSpot waits to serve clients with minor medical issues.

Patients can enter the 8-foot-by-7-foot pod and video chat with a local doctor. The doctor can release one or more of the six hatches next to the screen, revealing devices like a stethoscope or a blood pressure cuff, that a medical attendant will then use to check the patient.

Christine Suarez, the telehealth medical assistant at The Falls Florida Blue, said customers were skeptical at first about using the kiosk but most left pleased with their care. Services can cost up to $49 and are only available for Florida Blue policy holders.

The Falls retail store is the first to offer HealthSpot, which opened in mid-November, but more are planned in the future, said Penny Shaffer, Florida Blue South Florida market president.

“A lot of the conditions could be treated in a less expensive and more appropriate setting,” Shaffer said. “It’s driven a number of organizations to look for where those gaps are and try to fill those gaps.”

In South Florida, she said, Florida Blue has found that those gaps are in the way health care is provided to the area’s large Central and South American population.

Up next in retail health care will be CiniSanitas, three clinics to be opened in Kendall, Doral and Miami Lakes by September that offer a variety of services for these populations.

In a partnership between Organizacion Sanitas Internacional, a health care business group in Colombia, Venezuela, Peru and Brazil, and Florida Blue’s parent company Guidewell, the integrated care clinics will tap into a model of health care that South and Central American populations are familiar with.

In Latin America, clinics are “the more preferred setting for care that provides really integrated health outcomes,” Shaffer said.