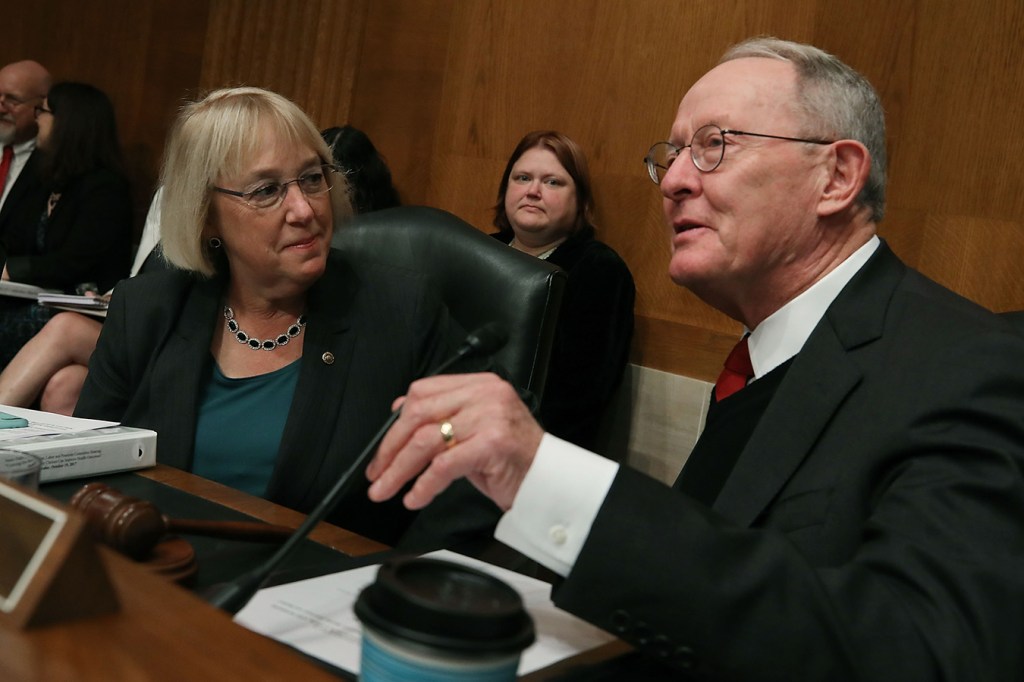

Sens. Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.) and Patty Murray (D-Wash.), who are pushing a major legislative package to lower health costs, announced their favored solution to handle disputes about surprise medical bills.

Those unexpected and often high charges patients face when they get care from a doctor or hospital that isn’t in their insurance network are a perpetual complaint from consumers.

Alexander and Murray formally introduced their wide-ranging bill Wednesday, but they had offered a broad outline before without taking a stand on how to mediate between health care providers and patients on the surprise bills.

When a patient is seen by a doctor who isn’t in their network, the Alexander-Murray bill says insurance would pay them the “median in-network rate,” meaning the rate would be similar to what the plan pays other doctors in the area for the same procedure. If there aren’t enough other doctors covered by the plan to compute a median in-network, the plan would use a database of local charges that is “free of conflicts of interest.”

Alexander said in a written statement that his decision was swayed by an assessment by the Congressional Budget Office, which “indicated that the benchmark solution is the most effective at lowering health care costs.”

According to early numbers from a CBO report, benchmarking could save $25 billion over the next 10 years. Loren Adler, associate director of USC-Brookings Schaeffer Initiative for Health Policy, said that means commercial insurance premiums would be reduced by about a half-percent.

“That’s pretty significant for federal policy,” Adler said.

The formula is similar to what a different group of bipartisan senators, led by Sen. Bill Cassidy (R-La.), proposed earlier this year. The critical difference is that in the Cassidy bill if the insurer and doctor can’t agree on a median-in-network rate, they can take their case to an independent arbitrator.

The provider community has pushed back on any attempt to set a “benchmark” for physician pay, like the one in Alexander and Murray’s bill.

At a hearing Tuesday before the Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee — of which Alexander and Murray are the chairman and ranking member, respectively — Tom Nickels, executive vice president of the American Hospital Association, said benchmarking would hurt efforts to set up broad insurance networks because providers and insurers would already know what they would be paid for surprise bills and it would be hard to recruit physicians to adequately staff hospitals.

“Health plans and hospitals have a long-standing history of resolving out-of-network emergency service claims, and this process should not be disrupted,” he said in written testimony.

Alexander also pointed out that Rep. Frank Pallone (D-N.J.), chairman of the House Energy and Commerce Committee, and Rep. Greg Walden (R-Ore.), the ranking member of that committee, have also recommended this proposal.

Although it isn’t the most aggressive solution the committee could have picked, according to Adler, it’s still a positive step, and he said it was promising that an influential health committee in the Senate and an influential health committee in the House are on the same page.

“There’s some logic to moving trains in the same direction,” Adler said.

The Alexander-Murray legislation says that any care the patient receives would count toward their in-network cost sharing, like their deductible, coinsurance or copay.

Once they are stable and lucid after an emergency, patients must be given written notice that they are going to be seen by an out-of-network doctor, an estimate of how much that could cost, and a list of in-network doctors or facilities where they could seek care.

The bill specifies that the notice must be short, easy to read and that consent to see an out-of-network doctor is clearly optional. If the patient doesn’t get this document, they can only be billed at an in-network rate.

Clarification: This story was updated on June 20 at 8:30 a.m. ET to make clear that the “median in-network rate” being proposed by in this legislation would be similar to what the health plan pays other doctors in the area, not what it charges them.