BERKELEY, Calif. — Again and again in the United States, anti-obesity crusaders have been stymied wherever they’ve tried to impose new laws on soda sales: in New York, ex-Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s plan to limit soda size was tossed out by the state’s highest court, proposed taxes in the northern California cities of El Monte and Richmond were voted down and the Washington, D.C. city council failed to pass an excise tax on soda.

Yet the successful enactment earlier this year of a nationwide tax on sugary drinks in Mexico has been a shot across the bow of Coca-Cola, Pepsi and other big soda makers, with Coca-Cola announcing a drop in profits, in part because of a decline in sales in its Latin American business.

Now, the soda industry is going to war in a pair of election battles in San Francisco and Berkeley, two of the most liberal cities in the U.S.

The measures, which voters will decide on Nov. 4, would impose a penny per ounce tax on sugary drinks in Berkeley and a two-cent per ounce tax in San Francisco. Citing the drinks’ impact on the nation’s obesity crisis, diabetes and other health problems, the money raised from the taxes would be directed, in San Francisco, toward childhood nutrition and recreation, and, in Berkeley, into the city’s general fund.

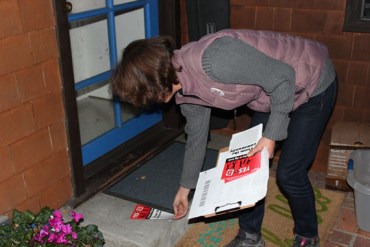

On a recent evening, soda tax supporter Pam Gray set off among the steep sidewalks in her north Berkeley neighborhood to convince voters here to support the measure. After knocking on doors, she finds a neighbor, Katy Wilson, being pulled on the end of a leash by a friendly dog. Wilson agrees kids eat too much sugar, and she is alarmed by the growing obesity rates, but she tells Gray she’s already made up her mind: She is going to vote no.

“I don’t think the measure gets to the root cause which is our attitudes toward eating, drinking and taking care of ourselves. It’s just, like, a penalty,” says Wilson.

The two neighbors debate the merits for some time, and Gray tries to make the case that Berkeley—where one out of three kids will develop diabetes, according to city officials— has to start somewhere: “The very initial steps around taxing tobacco started with some very small legislative steps,” Gray says, “This is really Berkeley’s attempt at beginning that process.”

The comparison to the declining tobacco industry is often cited. Vivien Azer, a stock analyst at Cowen and Company, covers the soda and tobacco industries and jokingly calls herself “The Sin Analyst.” She says the declines in soda volumes are eerily similar to those seen for cigarettes.

“If you look at the shape of the cigarette industry volumes, they were growing into the early 1980s, and they began to decline from there,” Azer says. “What we’ve seen in soda, is that volumes have been declining for about 10 years now, so I would argue that soda is about 20 years behind cigarettes.”

The early health concerns that led to a drop in cigarette purchases were followed by per-pack taxes and local and state smoking bans, and those measures have led to fewer teenagers and young adults taking up the habit. Soda drinkers, too, tend to start young, and if they haven’t established themselves as high volume consumers early in life, Azer says “the likelihood of them stepping up their consumption over time is relatively low.”

Along Berkeley’s main streets and in the underground subways here, advertisements blasting the proposed soda tax are everywhere. The American Beverage Association, the soda industry’s lobbying group, has spent about $1.7 million fighting the measure in Berkeley, and $7.7 million in San Francisco, according to state campaign filings. Roger Salazar, a spokesman for the ‘No’ campaigns, says these kinds of taxes have failed to pass in 30 cities and states across the country, and San Francisco and Berkeley will be no different. “While they try to paint it as a launching pad, it’s more a last gasp,” he says.

Salazar says cities have more important priorities than deciding what their residents should be drinking. He adds that taxes don’t get at the root of the obesity epidemic. “Taxing beverages is not going to change behavior or teach people about healthy lifestyles,” he says.

But soda taxes are particularly worrisome to beverage companies, say economists, because soda drinkers are less tolerant of price increases than, say, cigarette smokers. And as a result, soda consumers do change their behavior. Matthew Harding, an economist at Duke University, recently analyzed more than 100 million supermarket purchases in the U.S., and he found Americans spend about 10 percent of their food budget on sugar sweetened beverages, including soda. But when supermarkets raised those drink prices, consumers, including low-income consumers, made more nutritious purchases. “Sugar intake dropped by almost 20 percent and calories by 8.5 percent,” Harding says.

Soda companies have come up with one response to the pressure to cut empty calories: make the cans smaller and charge more. For Coca-Cola’s so-called mini-cans, Azer says, the revenue per ounce is more than 100 percent higher than a regular can of Coke.