Source: UnitedHealth Center for Health Reform & Modernization

The percentage of rural Americans with insurance could grow faster than those in urban areas under the federal health care overhaul law, a boon for the newly insured, but one that will put additional pressure on areas already short of doctors, a study out today says.

About 5 million more rural Americans will have coverage by 2019 – either through the insurance exchanges or Medicaid – a 16 percent increase, according to a study by the research arm of insurer UnitedHealth Group. That compares with a 13.5 percent increase in urban areas, where an additional 25 million people will gain coverage, the report says.

The insurer used census data and a simulation model developed by the Lewin Group to arrive at the estimates, cautioning that they are “subject to uncertainty.”

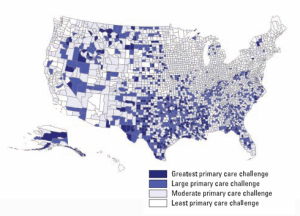

Still, the expansion in rural America would come even as many areas already have below-average availability of primary care doctors – along with higher-than-average rates of chronic health problems, such as heart disease and diabetes.

“This is clearly a major challenge for the next two and a half years,” says Simon Stevens, executive vice president of UnitedHealth. “On a region by region basis, there needs to be a concerted plan to think about how health care will be organized to react to these expansions.”

Since much of the growth in the insured will be because of coverage expansions in Medicaid, the state-federal program for the poor, United asked doctors if they currently accept new patients in the program and how likely they would be to continue to do so. Eighty-four percent of rural doctors currently accept new Medicaid patients, compared with 65 percent of urban physicians. Among rural doctors, 59 percent said they expect to be taking on new Medicaid patients in 2014, the year that the state-federal program for the poor will be expanded to make more Americans eligible, compared with 44 percent of urban doctors. Thirty percent or more of both groups said they didn’t know what they will do that year.

While the health care law does provide some funding for increased training and pay for primary care physicians, the report says the states also need to act to boost capacity.

States could, for example, allow mobile clinics to count toward requirements that insurers provide adequate networks of doctors. They could also make it easier for doctors to practice “telemedicine,” where patients are seen by doctors via video, telephone and other electronic consultations. One way to do that is to allow multi-state licenses, so a doctor in one state can see patients via telemedicine in another, Stevens said. The report also suggests that more states should allow nurse practitioners and physician assistants a greater role in seeing patients, offering treatment and prescribing medications. Such changes in “scope of practice,” are controversial – and often fought by doctor associations.