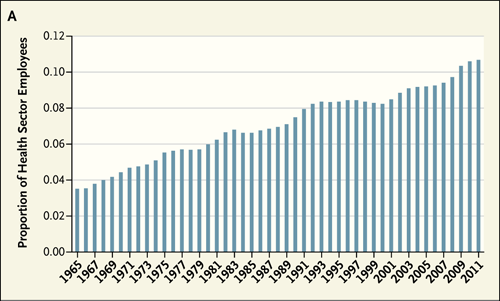

Health care employment has been the bright spot in the otherwise lackluster recent jobs reports. As overall employment decreased by 2 percent from 2000 to 2010, employment in the health care sector actually increased by 25 percent.

But that’s not necessarily a good thing, according to an opinion piece published in the most recent edition of the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Treating the health care system like a (wildly inefficient) jobs program conflicts directly with the goal of ensuring that all Americans have access to care at an affordable price,” write Katherine Baicker and Amitabh Chandra, two researchers from Harvard.

By 2020, almost one out of nine American jobs will be in health care, an April study from the Center for Health Workforce Studies projects.

As the country wrestles to reduce health care spending, which already consumes about 18 percent of GDP, those extra jobs could be a step in the wrong direction.

“Salaries for health care jobs are not manufactured out of thin air—they are produced by someone paying higher taxes, a patient paying more money for health care, or an employee taking home lower wages because higher health insurance premiums are deducted from his or her paycheck,” write the authors of the NEJM column.

Yet hospitals and politicians alike often tout the jobs that the health care industry creates in local communities. “The health care sector is an economic mainstay, providing stability and even growth during times of recession,” the American Hospital Association wrote in a fact sheet entitled “Economic Contribution of Hospitals Often Overlooked.”

The authors argue that the focus should instead be on improving health outcomes and efficiency, rather than simply more people working in the field, pointing to “mounting evidence that out health care system could deliver better care without spending more and that there are tremendous opportunities for improvements in productivity.”

Several provisions of the 2010 health care law aim to reduce inefficiencies by rewarding higher-value care and reducing some of the incentives for doctors to deliver more testing and care with unproven benefits. Such policies may serve to reduce health care employment, the authors argue, by “allowing us to get the same health outcomes with fewer health care workers.”

Some jobs in health care could be lost; however, taxpayers and workers in other fields would likely pay less in premiums.

“The bottom line is that employment in the health care sector should be neither a policy goal nor a metric of success,” they conclude.