To hear a patient’s heart, doctors used to just put an ear up to a patient’s chest and listen. Then, in 1816, things changed.

Lore has it that 35-year-old Paris physician Rene Laennec was caring for a young woman who was apparently plump, with a bad heart and large breasts. Dr. George Davis, an obstetrician at East Tennessee State University who collects vintage stethoscopes, said the young Dr. Laennec didn’t feel comfortable pressing his ear to the woman’s bosom.

“So he took 24 sheets of paper and rolled them into a long tube and put that up against her chest, listened to the other end and found that not only could he hear the heart sounds very, very well, but it was actually better than what he could hear with his ear,” Davis said.

Or, maybe it was poor 19th century hygiene — lice and the smell of an unwashed body — that kept Laennec from getting too close to his patient.

Either way, he went home and crafted a wooden cylinder with a hole down the middle and that became the first stethoscope.

It took a while for the art of listening to the body through a tube to catch on. But the new tool fit into an evolving idea that doctors needed a more focused approach to diagnosis, “that you should distinguish tuberculosis from a lung abscess — and not just call it all consumption,” said Dr. Steven Peitzman, a professor at Drexel University College of Medicine.

He said doctors used to get praise if they had the “ear” to hear and interpret the subtle body sounds that travel through a stethoscope’s rubber tubing; the stethoscope is the iconic symbol of a physician.

Vidya Viswanathan, a first-year student at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine, is still getting used to hers.

“You don’t realize until you are wearing it and trying to use it, how pokey it is in your ears,” she said. “I’m almost embarrassed to wear it because it implies I have knowledge I don’t have yet.”

Medical schools teach the art of listening.

“I am astounded at the things I’ll find with my stethoscope,” said Allison Rhodes, a third-year student at the Perelman School of Medicine. “I had a patient who had pneumonia, and it was really wonderful to be able to listen to her and say, ‘This is what I think it is.’ And then, later, see on the chest X-ray that, that was exactly what it was.”

But some argue that the stethoscope is becoming less useful in this digital age. Dr. Bret Nelson, an emergency medicine physician at Mt. Sinai Hospital in New York, said clinicians now get a lot more information from newer technology.

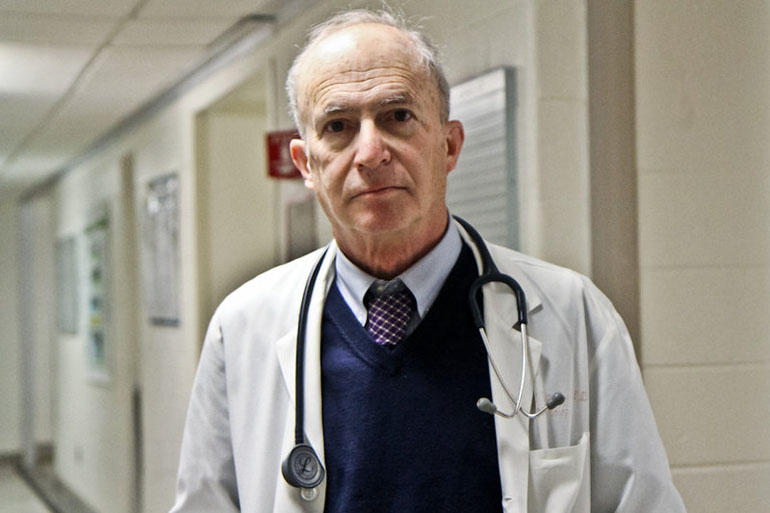

Some doctors say clinicians can now get much more information from newer technology than they can get from a stethoscope. Clinging to the old tool isn’t necessary, they say. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

An ultrasound, for example, turns sound waves into moving images of blood pumping and heart valves clicking open and shut; those visual cues are easier to interpret than muffled murmurs and may produce a more accurate diagnosis, Nelson said.

He admits the stethoscope is an icon, but doesn’t buy the argument that if you lose the stethoscope, you lose the tradition of “healing touch.”

“Pulling an ultrasound machine out of my pocket, or wheeling the cart over next to the patient [and] talking through with them exactly what I’m looking for and how I’m looking for it — the fact that they can see the same image on the screen that I’m seeing, strengthens that bond more than anything in the last 50 years,” Nelson said.

Nelson is 42 years old and graduated from medical school 16 years ago. He teaches medical students and said it’s helpful to show new learners what “lies beneath.” At Mt. Sinai, when medical students are taught to examine a heart, they learn how to use the stethoscope and an ultrasound machine on the same day.

“They know how to feel it, they know how to listen to it, and they know how to look at it,” Nelson said.

Still, obstetrician George Davis wants to keep the stethoscope around for a while. High-tech machines and imaging scans are great backup resources, he said, but his stethoscope helps him figure out which patients actually need additional testing.

“How much do those ultrasound machines cost?” Davis asked. “I can get a good stethoscope for less than $20. We are not going to sit there and do an echocardiogram on every patient who walks through the door.”

Davis worries that a whole generation of doctors is learning to rely too much on technology; he wants to hold on to first-line tools that are safe, effective and cheaper.

“Shouldn’t we be using what is low-tech and practical?” he asked.

Nelson counters that point-of-care imaging is becoming less expensive every day. Twenty years ago, he says, an ultrasound machine was as big as a refrigerator and cost $400,000. Today, a handheld, portable device plugs into a computer tablet, and costs less than $10,000.

Many care providers in the community may even have an ultrasound in their pocket one day soon, he says, combined in a single device with, “a slide rule, a calculator, a flashlight, a phone, a computer terminal and 36 video games.” In other words: on their smartphone.

This story is part of a reporting partnership with WHYY’s health show The Pulse, NPR and Kaiser Health News.