AUSTELL, Ga. — UnitedHealthcare is betting $65 million that it can profit by making primary care more attractive.

With little fanfare, the nation’s largest health insurer launched an independent subsidiary in January that offers unlimited free doctor visits and 24/7 access by phone. Every member gets a personal health coach to nudge them toward their goals, such as losing weight or exercising more. Mental health counseling is also provided, as are yoga and cooking classes, and acupuncture. Services are delivered in stylish clinics with hardwood floors and faux fireplaces in their lobbies.

Harken Health is available only in Chicago and Atlanta, where it covers 35,000 members who signed up this winter on the Affordable Care Act’s insurance exchanges. UnitedHealth still sells traditional plans in those cities, too.

Harken’s lush operation might seem puzzling for a cost-conscious company such as UnitedHealthcare, which said in November it lost hundreds of millions of dollars on its Obamacare plans in 2015 and threatened to drop out of the exchanges in 2017.

But it’s not crazy. Health care analysts say Harken demonstrates the insurer’s search for a better way to provide affordable care and attract more customers. Its mission is to prove that convenient, no-cost primary care, delivered with top-notch customer service, can lower hospitalization rates and overall health costs. Harken spends twice as much on primary care as the average insurer, according to the company.

“At the end of the day, United wants to know if this system can better control costs, as it’s a lot cheaper to prevent disease than treat one,” said Liz Frayer, an employee benefits consultant in Atlanta.

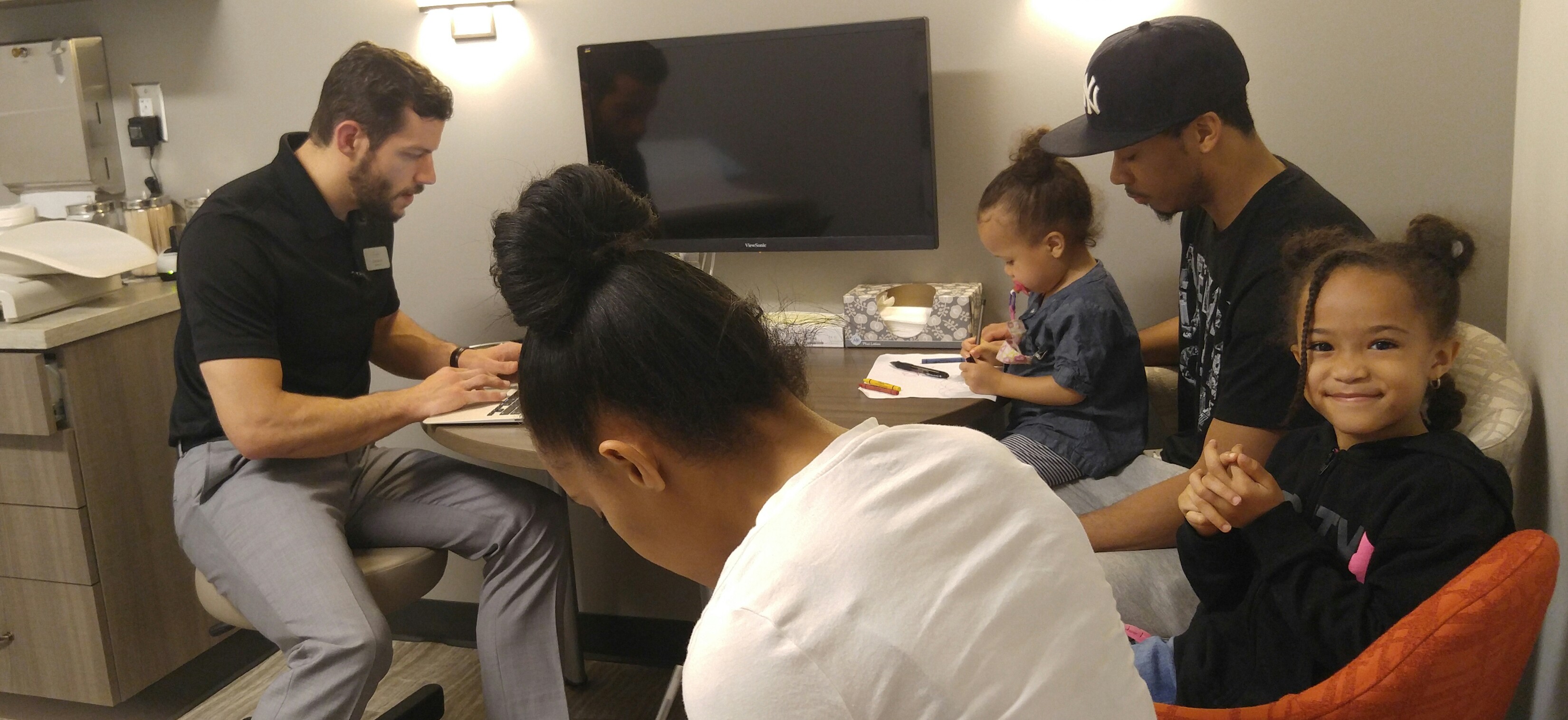

Tyler Harrison and his wife Rodiqa brought in 6-year-old Tyani, right, to the Harken facility in Roswell, Georgia, to get checked out. Colin Moran, a health coach at the facility, talks to the family. (Phil Galewitz/KHN)

Harken’s strategy is to get its members to seek care early to avoid costly problems down the road. That could pay off for Harken — if members stick with its plan for years. So far, many Obamacare enrollees have dropped or switched carriers each year to save money or to gain employer-sponsored coverage.

But two common consumer gripes about most Obamacare plans — high out-of-pocket costs for doctor visits and narrow networks of specialists and hospitals — don’t apply at Harken.

Harken offers six clinics in Atlanta and four in Chicago where its members can go for free primary care. When they must see a specialist or visit a hospital, UnitedHealth’s broad network is at their disposal. Harken plans are for individuals and small employers.

A Harken clinic has the ambience of a boutique hotel. Members enter brightly lit lobbies and exam rooms that are less so. Every room has a small table with chairs to encourage relaxed conversations. Several have no exam table or medical equipment at all — just a couch and chairs. Wall monitors in exam rooms let patients see notes that doctors and health coaches type into computers during appointments.

Harken’s primary care physicians are on salary, which means they have no financial incentive to order unnecessary tests and gives the plan greater control over how they treat patients. Doctors work closely with teams of nurse practitioners, social workers and health coaches who follow treatment guidelines that Harken hopes will ensure more efficient care.

Coaches meet with patients before and during doctor visits and, afterward, help them navigate referrals and insurance. All are trained in basic health services such as taking vital signs, but not all come from health care backgrounds. Some were fitness instructors and chiropractic assistants before joining Harken.

Richard Hall had a low-grade fever and sore throat when he walked into Harken’s clinic in Austell, just west of Atlanta, in March. After his health coach, Mary O’Keefe, took him to an exam room, they were soon joined by internist Austin Smith, casually dressed in an open-collared shirt and slacks. Harken doctors shun white lab coats.

Smith did a strep test, which was negative, and advised Hall that he likely has a viral condition that will run its course in a few days.

That’s it. Hall, like all patients treated in Harken clinics, never opened his wallet.

Not everything is free at Harken, however. Copays are required for specialists and prescription drugs. Members who need generic drugs for chronic illnesses can buy two-month supplies and get a third month free.

Hall, 55, had been without a doctor and insurance for more than 15 years when he signed with Harken last fall for coverage starting in January. Because of his low income, he qualified for a premium subsidy. Coverage for Hall and his wife costs him $161 a month.

Harken’s focus on wellness persuaded him to try it. A Harken health coach suggested ways he can lose weight and she’s available to answer questions about his care or coverage. “It’s better than anything I dreamed,” he said.

Other Harken members interviewed at Atlanta-area clinics recently also praised the care they’ve received.

Grace Hansen, 27, said her weekly meetings with a licensed social worker who helps her with mental health issues have been invaluable. The visits are coordinated with her Harken physician and health coach. “It’s so refreshing to have a wellness approach and having people here say, ‘What can we do to help you be in better health?’ ”

Testimonials like those please Harken CEO Tom Vanderheyden, who has held several executive positions at UnitedHealthcare since 2003.

Tom Vanderheyden, CEO of Harken Health, stands with a greeter at the Austell, Georgia, clinic. (Phil Galewitz/KHN)

Whether Harken succeeds depends on how doctors, coaches and customer service workers interact with patients, he said.

“The secret sauce is not in rearranging the operational or financial components of health care models. It is about recreating the relationships that have been lost in the modern system, relationships that will lead to better health,” Vanderheyden said. “We are finding the people that have a passion for caring for our members and unleashing their talents in a way that scales.”

Harken’s like-minded ally is Iora Health, a Boston-based company that’s reimagining traditional primary care by placing patients under the care of teams of doctors, nurses, coaches and social workers. Iora, which manages Harken’s clinics, also partners with Humana’s Medicare plans in Washington, Oregon and Colorado.

Iora gives patients hour-long appointments and 24/7 telemedicine access to doctors. Those have cut emergency room visits and hospitalizations, according to the company, but there are no peer-reviewed, published studies confirming that.

Features of Iora’s model — such as longer hours, more support staff and higher primary care spending per patient — have been tried elsewhere, especially in so-called patient-centered medical homes funded by the Affordable Care Act. Few have reduced overall patient spending or cut the frequency of patients’ hospital admissions.

Experience will determine whether Harken is the start of something new or a flash in the primary care pan.

Harken is not for everyone. Its clinics may not draw consumers unwilling to switch family doctors or internists.

Harken also could fail if people try it and don’t stay enrolled, warned William Custer, director of Center for Health Services Research at Georgia State University. Harken’s investment in primary care to prevent catastrophic, costly episodes such as heart attacks will only pay dividends for Harken if members stick with Harken for years.

“It’s a gamble,” Custer said.

For UnitedHealthcare, whose parent company reported $157 billion in revenue and $6 billion in profit last year, it’s a chance worth taking.