Chris Denny, who runs a small marketing firm in Santa Rosa, Calif., buys his own health insurance for $117 a month. An avid gardener, Denny, 27, describes himself as healthy and fit.

The same policy, from the same insurer, would cost a 60-year-old man $735 a month, according to an estimate on eHealthInsurance.com, an online marketplace that lists quotes and coverage from a variety of insurers.

Such a difference in cost – common around the country – doesn’t surprise Denny, who says older people use more medical care: “So is it unfair to charge them five times more? I don’t think so.”

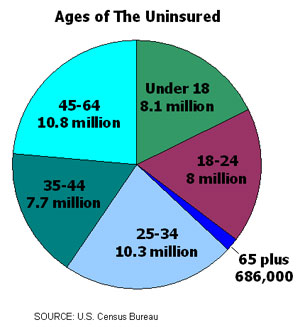

For years, insurers have charged older customers far more than younger ones, in part because of older residents’ higher use of medical services. Now, as Congress wrestles with a health care overhaul aimed at covering the majority of the 46 million uninsured, that discrepancy is one area targeted for change. The outcome could affect tens of millions of people – young and old – who don’t get insurance through their jobs and buy it on their own, as well as some small businesses. It would not affect people 65 and older, who are covered by Medicare, or people who work for large companies, which usually get group rates for health coverage.

Curbing The Age Gap

Nine states limit how much more older people can be charged than younger ones for individual health policies. The maximum ratio in these states is:

1 – The maximum factors in age, gender and geography combined

Source: Georgetown Health Policy Institute

Lawmakers face a delicate balancing act involving fundamental issues of fairness and cost. Limit insurers to charging only a small difference in monthly premiums between older and younger people, and the younger ones would likely pay far more than they do now. Allow a larger spread, and older residents may be priced out of coverage.

“It’s absolutely a double-edged sword,” says Marian Mulkey, a senior program officer at the California HealthCare Foundation, a nonpartisan group that studies health care. Currently, older customers pay insurers up to four or five times more than younger ones, Mulkey says.

As lawmakers craft legislation aimed at covering the majority of the 46 million uninsured, they are trying to narrow the price gap.

Proposals approved by House and Senate committees would limit insurers to charging older people no more than double what younger people pay. Only nine states now restrict the range insurers can charge individuals based on age.

The congressional limit would apply to insurance sold through proposed “exchanges” – regional or national marketplaces where insurers would offer a variety of policies – to individuals and small businesses.

But insurers want Congress to let them charge older Americans five times more than young ones.

The industry trade group America’s Health Insurance Plans said in a July 16 letter to House leaders that anything less than that would force many young people to pay more to “heavily subsidize the naturally higher health care costs of older individuals.”

“The policy question that needs to be answered is how much do you want young people to absorb?” says Karen Ignagni, the group’s president and CEO.

If the country doesn’t want to shift more costs to younger residents, Ignagni says, lawmakers should allow the wider spread – and back it up with additional subsidies for those 55 and older.

While none of the competing bills in Congress contains the 5:1 ratio, it is included in a policy options paper released in May by the key Senate Finance Committee, which is expected to finalize its bill after Labor Day.

Even advocacy groups are split. AARP, the lobbying group for those 50 and up, opposes the 5:1 ratio but supports a 2:1 ratio.

Meanwhile, a coalition of other groups representing older Americans wants age dropped as a factor entirely.

“We’re all going to get older, so charging someone an increased premium for something they can’t do anything about is simply ridiculous,” says Natale Zimmer, health policy director for OWL: The Voice of Midlife and Older Women. OWL and 27 other groups, including the National Senior Citizens Law Center and the Service Employees International Union, have asked Congress to require insurers to treat everyone equally when setting premiums.

‘Why are they picking on me?’

Maria Bishop, a 60-year-old resident of St. George, Utah, says she pays $500 a month for coverage – and was rejected by two insurers when she recently shopped for a cheaper plan. A third offered a policy with a lower monthly premium, but it included a $2,000 annual deductible, meaning she would pay thousands of dollars before coverage began.

Bishop, who describes herself as a fit, trim, non-smoker, says it isn’t fair to base premiums on age.

“There’s a lot of us who are very healthy,” she says. “Why are they picking on me when they have younger people on policies who are overweight, who smoke and don’t exercise?”

Last year, the insurance industry pledged to stop rejecting individuals for health reasons – and to discontinue using health as a basis in setting premiums – but only if Congress requires most Americans to carry coverage.

Age is currently one of many factors that go into premium pricing, along with an applicant’s health, geographic location and the type of coverage and benefits sought, says Karen Pollitz, project director at Georgetown University’s Health Policy Institute.

Average medical spending per person among 18-to-44-year-olds was $2,079 in 2006, the latest data available from the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Spending for 45-to-64-year-olds was $4,866, about 2.3 times more.

The health insurance industry trade group says the federal data simply splits ages into two large groups, while insurers generally have many more brackets.

“There’s a much greater ratio depending on how you cut the data,” says Robert Zirkelbach, spokesman for America’s Health Insurance Plans. “If you break it into quartiles there would be a five-to-one gap.”

Pollitz calls “obscene” the industry request for a 5:1 ratio.

“That’s just a tax on getting old,” she says.

Will young people enroll?

At the heart of the debate is how to get attract younger people – currently the group least likely to have insurance – to buy coverage.

Young people are attractive to insurers because they are generally healthy and have lower medical bills. Increasing their enrollment would help offset older, higher-risk people in the insurance pool, potentially moderating prices for everyone.

“Younger people will cross-subsidize older ones, but that’s the whole point of insurance,” says Nancy Metcalf, senior program editor of Consumer Reports. “If you’re young now, someday, if you are lucky, you will be 30 years older.”

All the proposals in Congress require most everyone to carry insurance and impose a financial penalty on those who do not. Still, young people won’t enroll if prices are set too high, warns James Gelfand, senior manager of health policy for the U.S. Chamber of Commerce.

“Young and invincible people don’t want any insurance, much less a gold-plated (plan),” which is how they may view policies if a 2:1 ratio makes them expensive or the plans include benefits they don’t want, he says.

If Congress limits insurers to charging older residents double what younger ones pay, Mulkey at the California foundation gives a “ballpark estimate” that premiums for younger people in her state could double. At the same time, premiums could decline by about 50% for older people.

“If you have someone in their 20s struggling to pay for a policy that costs $80 a month, and it goes up to $150, what would you have to do with subsidies or penalties to get them to buy it?” she asks. “Conversely, (for people in their 50s or 60s) if you could bring premiums down to $600, maybe they’re in a much better position to keep the policy. This is the challenge.”

Under current proposals, subsidies are planned for people earning up to 400% of the poverty level, or about $43,320 a year for an individual.

“No matter your age, if you are low-income, you will get a subsidy,” says OWL’s Zimmer.

How Massachusetts did it

In Massachusetts, where the state has long limited insurers to charging older people no more than twice the rate of younger ones, premiums for a 30-year-old Bostonian range from $214 a month to $599, depending on the level of benefits, according to a state Web site.

Those same plans for a 60-year-old range from $425 to $1,076 a month.

“Even with the limitations in Massachusetts, it’s very difficult for older people,” says Carol Pryor. of The Access Project, a nonprofit that works with local and national advocacy groups on health care issues, including medical debt and the uninsured.

Georgetown’s Pollitz says it would be difficult to assess how efforts to regulate age-based premiums have affected the young and old in other states because most do not post premium prices online. Yet she notes the gap in premiums is larger in states that have less regulation.

Pryor says instead of tinkering with premiums based on age and “charging this one more and that one less,” policymakers need to “look at other parts of the system where money can be saved,” such as changing payment systems to encourage more coordinated care.

Lawmakers who hammered out the state’s health care overhaul in 2006 believed the 2:1 ratio might deter younger people from signing up for coverage, so they created special “young adult plans” for those aged 18 to 26.

Those policies are less expensive – premiums for a 25-year-old Boston resident range from $146 a month to $223 – and don’t always include some benefits the state requires for other residents, such as prescription drug coverage. About 27%. of the 22,000 people who have enrolled in unsubsidized, private coverage through the state’s insurance exchange since the law passed have picked the young adult plans, according to state data.

During debate leading to the state’s 2006 health legislation, which requires most residents to have insurance, the AARP did not challenge the 2:1 ratio “because we knew it might derail health reform,” says Deborah Banda., the organization’s state director.

Now that Massachusetts has succeeded in getting most residents to enroll in health insurance, Banda says, it may be time to “fine tune the law” and drop age as a factor altogether.

Nationally, AARP is taking a similar tack: It has endorsed the 2:1 ratio, saying lower limits could be phased in over time.

John Rother, AARP’s policy director, says if lawmakers immediately require insurers to charge everyone the same amount, regardless of age, health or other factors, it would cause “sticker shock” for younger people.

“You can’t get there in one giant leap,” says Rother. “So 2:1 can really soften the impact on the young, while keeping premiums relatively affordable for the older population.”

Deborah Chollet., a fellow at Mathematica., a nonpartisan policy research group in Princeton, N.J., says no matter what Congress decides, there will be people who can’t afford coverage because they earn too much for subsidies but not enough to pay for insurance.

Setting the ratio at 5:1 will cause more older people to be unable to afford coverage, while setting it at 2:1 could leave out more younger people. The question, she says, is which group does society want to help the most?

“There really isn’t a right answer here,” Chollet says. “There’s a decision to be made, but not a right answer.”

KHN reporter Jennifer Evans contributed to this story.