MARIN CITY, Calif. ― A small band of volunteers started the Marin City Health and Wellness Center nearly two decades ago with a doctor and a retired social worker making house calls in public housing high-rises. It grew into a beloved community resource and a grassroots experiment in African American health care.

“It was truly a one-stop shop,” said Ebony McKinley, a lifelong resident of this tightknit, historically black enclave several miles north of the Golden Gate Bridge. “And it was ours.”

By early 2020, the center had a multimillion-dollar annual operation with two clinics, in Marin City and Bayview-Hunters Point, a predominantly black community in an industrial section of southeastern San Francisco. The clinics offered primary care geared to low-income residents of color, as well as access to dentists, psychotherapists, a substance abuse clinic and chiropractor.

In Marin City, ladies shouldering empty tote bags lined up on Tuesday afternoons to score free fresh produce at the clinic’s weekly Food Pharmacy program ― a big hit in a neighborhood where for years grocery shopping meant stopping by the dollar store for a couple of pork chops and maybe a withered, overpriced apple from CVS.

But in the wake of the coronavirus shutdown, there are worries about the future of this neighborhood clinic and others like it. Community health centers ― which provide medical services for 1 in 6 Californians ― have been forced to cancel in-person patient visits, and more than 200 of the clinics have closed since March. Despite several tranches of emergency government aid, the losses have forced widespread layoffs, said Carmela Castellano-Garcia, president of the California Primary Care Association.

“When your patient numbers go down by 66%, and that’s your main source of revenue, it calls for some drastic measures, unfortunately,” said Brenda Crawford, interim CEO of the Marin City Health and Wellness Center (MCHWC).

The Marin City Health and Wellness Center was launched by a group of activists frustrated over health disparities they saw in this historically black community, which went decades without easy access to basic medical care in one of the state's wealthiest suburbs. "We literally had medical professionals who didn't want to lay their hands on black people," says resident Terrie Green, who helped found the clinic. (Rachel Scheier for KHN)

The Marin City Health and Wellness Center has expanded from an all-volunteer local operation to two clinics serving low-income African American neighborhoods with a chiropractor, a substance-abuse clinic, a dental van and a birth center. But now many services have been suspended or canceled and providers laid off. (Rachel Scheier for KHN)

In April, the clinic laid off 10 people ― almost a fifth of the staff ― just as an avalanche of data emerged showing the novel coronavirus wreaking a disproportionate burden of illness and death on black communities.

African Americans account for 13.4% of the population but nearly 60% of COVID-19 deaths, according to a national study released in May. Blacks in the U.S. have a relatively high prevalence of conditions such as asthma, obesity, heart disease and diabetes that put them at greater risk of COVID complications, and are more likely to live in communities with low-wage jobs and less access to decent medical care.

The residents of Marin City have a front-row seat to such inequities. Golden Gate Village, its aging public housing project, remains a pocket of poverty and unemployment in one of America’s wealthiest counties. Last year, its struggling public school was hit with California’s first desegregation order in half a century.

Marin City took shape during World War II, as some of the thousands of new arrivals who flooded the Bay Area to work in shipyards were housed on the swamplands north of Sausalito. In “On the Road,” his 1950s almanac of traversing the United States, Jack Kerouac described the dormitories as “the only community in America where whites and Negroes lived together voluntarily.”

Marin County today is known for its redwood trees and Tesla-driving tech executives. It is also one of the most segregated counties in California, stemming in part from discriminatory policies that barred blacks from relocating within the county after the war’s end.

A nonprofit in 2018 rated Marin home to the largest racial inequities of any county in the state. And while it was ranked the healthiest county in California for nine of the past 10 years, black residents here live on average only half as long as whites, according to the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Retired teacher and longtime Marin City, California, resident Florence Williams attends a June 2 march that drew at least 1,000 people from around the county to protest the death of George Floyd in police custody in Minneapolis. Local activists used the occasion to protest inequities that left historically black Marin City cut off from one of America’s wealthiest counties. (Rachel Scheier for KHN)

A half-dozen failed redevelopment plans between the 1950s and the late 1980s left Marin City without a supermarket, school or post office. For residents without a car, getting to the nearest clinic for a Pap smear or a blood pressure check required an hour-long trek involving two buses followed by a walk up a steep hill. “Or they just didn’t go anywhere,” said Terrie Green, a longtime Marin City resident who helped found the center.

Bad health was something she knew well. Two of Green’s brothers died of heart attacks, and a third of a stroke at age 57. Her father succumbed to diabetes complications after losing several toes and one leg below the knee to the disease.

“Folks was having funerals it looked like every other week,” said Green. “I was tired of that.”

In 2002, she quit her job as a county mental health worker to focus on bringing a clinic to Marin City. As a member of a community group called ISOJI, the Yoruba word for “resurrection,” Green organized health fairs in the bustling parking lots of Marin City’s peach-colored public housing towers, setting up a blood pressure machine alongside kids riding scooters and old men playing dominoes.

Accompanied by a family physician with a practice in neighboring Sausalito, she did home visits at the apartments of elder residents. “I knew everyone, so I’d ask questions, and they’d open the door, and then he’d do the medical piece,” said Green. “He could not believe what he was seeing in Marin City ― the asthma and high blood pressure, the levels of chronic disease.”

MCHWC opened its Marin City clinic in 2006 using $225,000 in cobbled-together seed money.

Dr. Carianne Blomquist joined the clinic a few years later, becoming the first doctor to set up an office in Marin City since the 1950s. Her personable approach brought a diverse clientele to the clinic’s cramped offices in a scruffy community center, one wall decorated by a mural of Barack Obama and Martin Luther King Jr. In the parking lot, moms in SUVs and gentlemen leaning on canes passed muscled young men on their way to the boxing gym next door.

MCHWC is one of about 1,400 community health centers across the country that function as a safety net for the poor and uninsured. Conceived by civil rights activists during the 1960s, such facilities have steadily expanded as studies showed they improved the health of communities. The passage of Obamacare in 2010 brought in millions of newly insured patients.

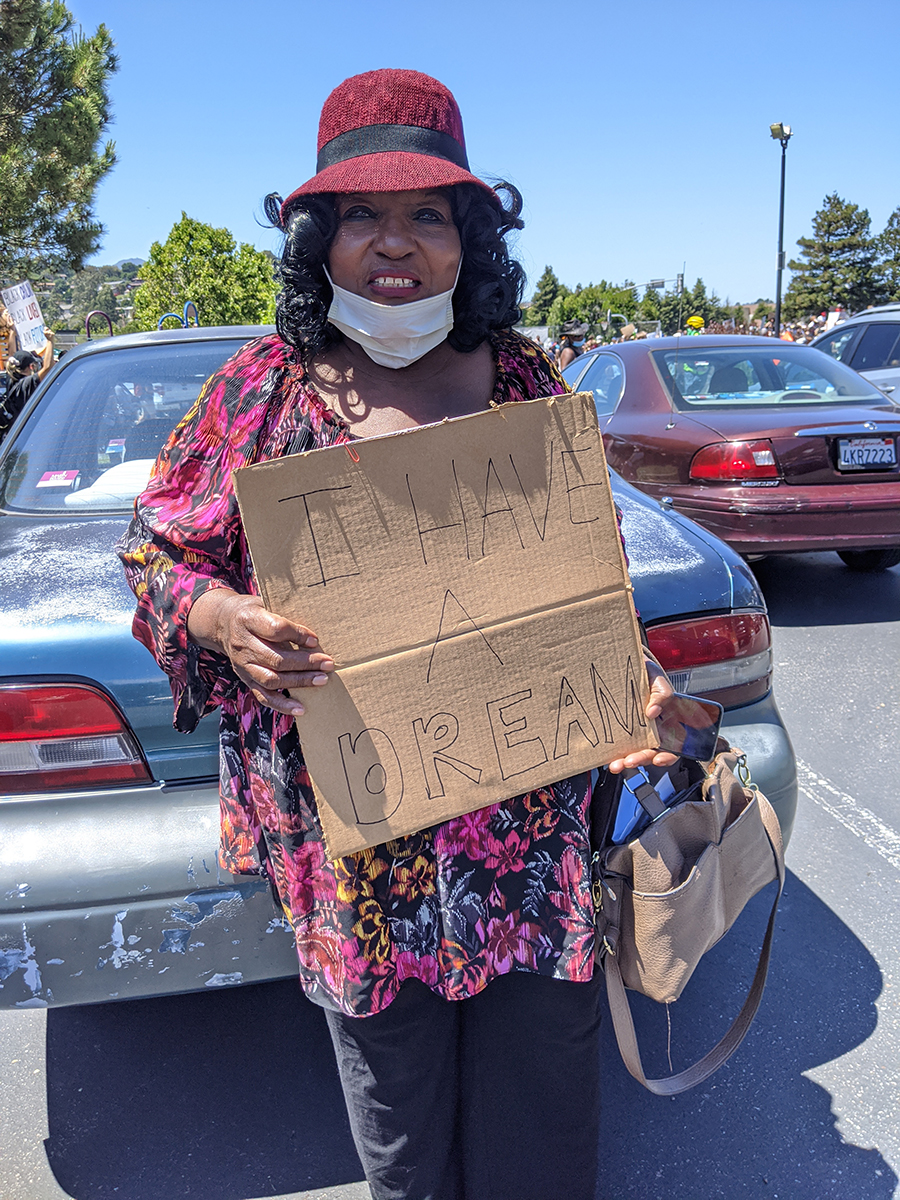

Chenetta Richardson, who was born in Marin City, holds a sign at a June 2 march and demonstration to protest police violence against black Americans. Marin County, despite its liberal politics, has among the widest racial disparities in the state. (Rachel Scheier for KHN)

In 2016, MCHWC opened a clinic in San Francisco’s Bayview-Hunters Point, like Marin City a working-class island amid the world’s highest concentration of billionaires. In the 2000s, it had the highest rate of childhood asthma in the city and an incidence of infant mortality on par with Jamaica.

The clinic opened in an old medical building where the neighborhood’s last private family doctor, Arthur Coleman, had operated until his death at age 82 in 2002.

Patient Gail Hampton, 64, came in the first time with such a debilitating fear of needles that she’d shake uncontrollably at the mere sight of a white coat. But Hampton soon began recommending the clinic to everyone from her grandkids to her church group. “They treated you like they wanted to help you,” she said. “Not just take your Medicare card and get your money.”

She was shocked to get a phone call in early April notifying her that her dentist and nine other employees were being let go. An earlier shake-up in leadership had led to the resignation of several providers including Blomquist, who quit in December and has not been replaced.

Under Crawford, a retired management consultant who took the helm in mid-2019, several services have been suspended, including an experimental high school for troubled teens and a birth center designed to address the staggering infant and maternal mortality rates among black women. Crawford said the birth center will reopen, but some are skeptical.

“It feels like a disservice to the community to allow the clinic to fall apart the way it is during this pandemic, which is killing black people,” said Dr. Joshwin Hall, a Bayview-Hunters Point native and a dentist at the clinic until he was laid off in April.

Green has been “beating the bushes” to open a drop-in coronavirus testing site at the clinic, so far without much luck. In the meantime, volunteers have been distributing “essential bags,” with supplies like thermometers and soap, and information on protecting against the virus.

The effort reminds Green of nearly 20 years ago, when she led the campaign to open the clinic.

“We’re still fighting,” she said.

This story was produced by KFF Health News, which publishes California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation.