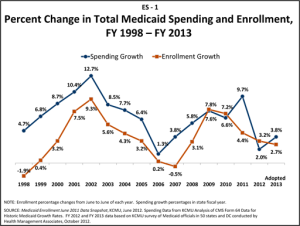

In a sign of the improving national economy, Medicaid spending growth this year slowed to 2 percent as enrollment in the state-federal health insurance program for the poor also slowed for the third consecutive year, according to a report released Thursday.

In 2011, Medicaid spending soared by nearly 10 percent, which helped put the entitlement program in the crosshairs of politicians looking to lower the federal deficit and ease pressure on state budgets. The increase this year is the smallest since 2006, said the report, based on a 50-state survey by the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. (KHN is an editorially independent program of the foundation.)

Advocates and critics of Medicaid clashed over the significance of the trend. Supporters viewed it as a sign of costs coming under control, while those that want the program overhauled said history shows spending will again surge.

Enrollment growth in Medicaid slowed to 3.2 percent this year, down from 4.4 percent last year and 7.2 percent in 2010. There are 62 million people in the program.

Other factors affecting spending growth included actions by states to cut benefits and reduce reimbursement rates to hospitals and doctors, and changes in how patients receive care.

States are projecting the slowdown in enrollment to continue in 2013, the report says. Spending, however, is expected to increase 3.8 percent.

“We believe this is the second slowest spending growth in the history of the program,” said Vernon Smith, a co-author of the study and managing principal at consulting firm Health Management Associates. Kaiser has done the annual Medicaid survey since 1998. “States are working very hard to improve value and slow the rate of growth of Medicaid.”

In the past year, states had extra incentive to control spending because $100 billion in extra federal funding to state Medicaid programs as part of the federal stimulus law ended in June 2011, Smith said.

Among the cost cutting efforts:

— Forty-five states froze or lowered provider rates in 2012 and 42 states reported plans to do so in 2013.

–Eighteen states in 2012 and eight states in the 2013 budget year starting in July reported eliminating, reducing or restricting benefits. Limits on dental and vision services, personal care services and medical supplies were most frequently reported.

— This year, 20 states reported expanded use of managed care, primarily by extending it into new counties or by adding new categories of recipients, such as the disabled. For 2013, 35 states reported they were expanding managed care, including 10 states that indicated plans to implement managed long- term care. Many states contract management of Medicaid services to private insurers.

President Barack Obama and GOP nominee Mitt Romney have opposing plans for the program. Obama’s health law will add as many as 17 million people to the program starting in 2014 by expanding eligibility to 133 percent of federal poverty, or $31,000 for a family of four. Romney wants to give states block grants for Medicaid, granting them greater flexibility and cutting federal funding by $100 billion a year.

Matt Salo, executive director of the National Association of Medicaid Directors, said he didn’t think the slowdown in enrollment and spending growth will have any “effect on the efforts to discuss block grants or other significant changes to the program.”

Michael Cannon, director of health policy studies at the conservative Cato Institute, said the report does not diminish the need to block-grant Medicaid. “Medicaid is so inefficient, we would need to block-grant it even if spending fell, which it did not,” he said. “In the past, the rate of spending growth has slowed even more than this, only to surge again.”

But the liberal Center on Budget and Policy Priorities had another take. “This report shows the program … is not out of control and over the longer period Medicaid is growing more slowly than Medicare and private coverage and this year even more so,” said Judith Solomon, vice president for health policy. She added, however, that some of the steps states are taking to control spending—primarily cutting fees to doctors and hospitals—are not sustainable because they will eventually reduce Medicaid recipients’ access to care.

Arkansas Medicaid Director Andy Allison is encouraged by the trend.

“I don’t know what impact this reduction in Medicaid growth will have on federal budget discussions, but I do think federal policymakers should take note,” he said. “If states are taking steps to control the rate of growth in Medicaid spending, this will pay a budget dividend to both states and the federal government, and should be a factor in deciding what additional steps the federal government needs to take.”

The federal government pays for about 57 percent of the $400 billion Medicaid program.