SAN FRANCISCO — Anne and Omar Shamiyeh first learned something was wrong with one of their twins during their 18-week ultrasound.

The technician was like, well there’s no visualization of his stomach,” said Anne. “And I was like, how does our baby have no stomach?”

It turned out that the baby’s esophagus was not connected to his stomach. He also had a heart defect. At the very least, he was likely to face surgeries and a long stay in intensive care. He might have lifelong disabilities.

This was only the start of an eight-month ordeal for the Shamiyeh family.

Decisions about how much care to offer very sick family members are always challenging, but they can be particularly wrenching for parents like the Shamiyehs, who face harrowing choices at what’s supposed to be a wonderful time — the beginning of a life.

As doctors and families consider how far to push medical care, a chasm can open between the parents’ hopes and what providers consider realistic.

For the Shamiyehs, the first major decision was whether to “selectively reduce” — the clinical term for aborting one fetus in a multiple pregnancy. “Omar and I were very uncomfortable with that. We really wanted to see what he was going to be like, and what life had to offer,” Anne said.

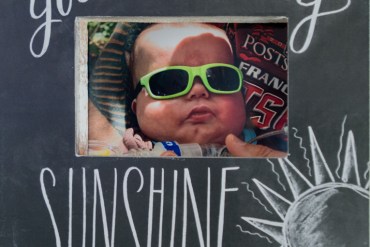

A photo of Kai Shamiyeh on the day he was taken outside for the first time. Anne says the family thinks of Kai as their sunshine. (Photo by Heidi de Marco/KHN)

That decision meant the twins, a boy and a girl, would likely be born premature. As it turned out, they were delivered by C-section at 30 weeks — about two months early — at UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital.

The boy was named Kai, the girl Malia. Each weighed about three pounds. They were rushed immediately to the NICU, where that night, Kai had his first surgery.

Malia went home after about five weeks. But Kai had a long road ahead. He was on a ventilator, had to be fed through a tube directly into his stomach and was still struggling to survive. Eventually, he was diagnosed with CHARGE syndrome — a rare genetic condition that can result in severe cognitive and physical disabilities.

About the time Malia went home, the doctors and nurses sat down with the Shamiyehs to discuss Kai’s treatment. They needed to know whether the family wanted a tracheostomy, in which surgeons would insert a breathing tube directly into Kai’s neck to ease passage of air into his lungs.

“It seemed awful,” Anne said. “We were both really unhappy with that but we understood it wasn’t a choice, it was something we had to do.”

But Dr. Liz Rogers, a UCSF neonatologist who cared for Kai, saw it as a significant decision.

“To be very honest, for many, many of our families, the point of decision around a tracheostomy is a major, major time when families say this has gone on for too long and it’s not what I want for him.”

Anne had real hope for Kai’s future, despite the pessimism of some doctors.

“I kept thinking, maybe that doctor’s view of quality of life is different from mine. And maybe for me loving my child and having him feel love is enough,” said Anne. “And it’s ok if he can’t talk. Maybe he’ll wear a diaper until he’s 5, and maybe he’ll be in a wheelchair, but that’s ok. Because he’ll be alive and he’ll be my child.”

Omar Shamiyeh, 42, looks through Kai’s photo book on Oct, 22, 2015. (Photo by Heidi de Marco/KHN)

Studies suggest that providers do tend to have a different view of quality of life than parents. In Kai’s case, many of his day-to-day caregivers — the nurses — felt Kai was suffering unnecessarily.

Diedre Miller says she was one of just a handful of nurses in the NICU willing to be part of his primary care team. It was clear to all of them, she said, that Kai wasn’t going to make it. Miller says she felt comfortable caring for Kai but faced pressure from other nurses.

“A lot of people thought OK, well let’s just offer the Shamiyehs the opportunity to withdraw care today. And as a primary nurse you knew that the Shamiyehs were never going to agree to that, and you knew that [Kai] had joy in his life,” she recalled. “But you go into the break room and everybody wants to talk about it, and everyone wants you to be the person to tell the Shamiyehs.”

There’s often a lag between when health care providers and parents sense a child isn’t going to make it. Researchers found, for instance, that oncologists realized children were going to die months before the parents.

Anne Shamiyeh prays with her husband, Omar Shamiyeh, and two daughters, Zara and Malia, before dinner on Oct.19, 2015. Anne says their faith played a strong role in dealing with the loss of Kai. (Photo by Heidi de Marco/KHN)

But “as easy as it is to say we knew Kai was going to die and we knew he was going to have a difficult life, gosh, what if we had been wrong?” Miller said.

From Anne’s and Omar’s perspective, Kai had many happy moments. They visited every day, always with Malia in tow. He smiled, cooed and connected with them. But he wasn’t getting better.

In May 2013, five months into Kai’s stay in the NICU, the Shamiyehs and their doctors sat down to talk about whether they wanted to go forward with the heart surgery that had been on the calendar since he had been born. It would have to be done if Kai was ever to leave the hospital.

The surgery wouldn’t help, doctors explained, and he might die during the operation. This time, Anne and Omar decided not to go forward.

“So that was the day we found out we wouldn’t ever be bringing Kai home,” Anne said.

Anne Shamiyeh reads to her daughters Zara and Malia on Oct. 22, 2015. Anne says the girls talk about Kai all the time. (Photo by Heidi de Marco/KHN)

Two weeks later, Kai developed an infection that they couldn’t treat. On June 5, 2013, he passed away in his mother’s arms.

There were real costs to Kai’s six-month stay in the NICU. Based on billing statements, the Shamiyehs calculate that the charges for Kai’s care added up to more than $11 million, though their insurer likely negotiated a lower rate.

There were also consequences for Kai’s twin sister Malia, whose parents were mostly focused on her brother during her first 6 months of life. She had speech and physical delays, although at age 3, she’s already caught up.

Kai Shamiyeh’s memorial card is posted on the refrigerator. “Kai is part of our everyday life,” said Anne Shamiyeh. (Photo by Heidi de Marco/KHN)

Looking back, Omar says he wonders if they went too far. “It’s really hard to think for 5 months he was going through all this pain and all this stress. You wonder if you made the right decision in keeping it going, you know?” he said.

But Anne, who is now studying to become a NICU nurse, says she does not regret giving their son the best possible chance at life.

She’s at peace with their decisions — both to try to save him and to let him go.

Jenny Gold wrote this story while participating in the California Health Journalism Fellowship, a program of USC’s Annenberg School of Journalism.