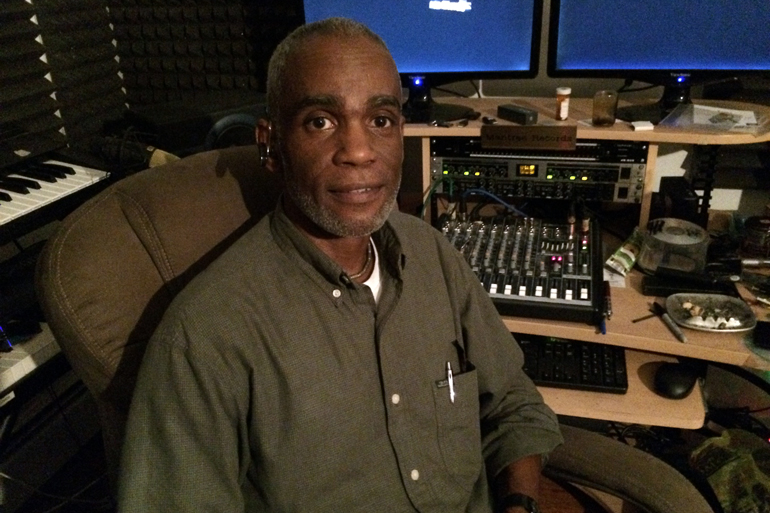

Recording and mixing music is Vernon Thomas’ passion, but being CEO and producer of Mantree Records is not his day job. He’s an HIV outreach worker for a local county health department outside Newark, N.J. He took what was to be a full-time job in May because the gig came with health insurance – and he himself has HIV, the virus that causes AIDS.

But then the county made it a part-time job – and Thomas lost that coverage before it started.

“Benefits are more important than the money you’re making,” Thomas says.

The Affordable Care Act’s third open enrollment season started Nov. 1, and federal officials are hoping to reach about a million people like Thomas across the country. Newark has an estimated 112,000 uninsured people, around one-third of the city’s population. It is one of five areas – along with Houston, Dallas, Chicago and Miami – where the federal government is focusing enrollment efforts. Altogether, Washington will spend more than $100 million on marketing and enrollment.

Why has Thomas sat on the sidelines for Obamacare’s first two years? He values insurance and regular health care, but he hasn’t fully understood what the law offered him.

He gets the medications that bolster his immune system, care of the federal government’s AIDS Drug Assistance Program. But it doesn’t cover anything else. Thomas says he’d like more medical care – particularly a regular doctor who could keep an eye on issues that worry him.

“Prostate cancer runs in my family on both sides. My mother and her mother and her brother all had diabetes. My mother had hypertension also,” Thomas says. “Fortunately, I have low blood pressure. But now they’re saying I have high cholesterol.”

Thomas’ part-time job doesn’t pay a lot, yet he makes too much to get free health care from Medicaid. Because his income is below 400 percent of the federal poverty guidelines (about $47,000 for an individual), he’s eligible for government subsidies to make an Obamacare plan more affordable, but he says it’s still too expensive – the cost of living in Newark is high for him. So he goes without – and keeps his fingers crossed.

“I try not to think about it –getting sick,” he says.

Even with a job in a health-related field, Thomas didn’t know the health law’s benefits for people in his income bracket. He didn’t realize that his earnings entitle him to enough assistance from the government to bring his premium down to $100 or less and that he also qualifies for “cost-sharing support,” which picks up much of the deductible and other out-of-pocket expenses. People who make 250 percent of the federal poverty guidelines (about $29,000 for an individual) can get the cost-sharing support.

Brian McGovern, head of the North Jersey Community Research Initiative, says overcoming misperceptions about Obamacare has been one of his staff’s biggest jobs. “It’s always been about trust with some of our patients,” he says.

Susan Nash from the Chicago law firm McDermott Will and Emery says for millions of people living paycheck-to-paycheck health insurance is still too expensive.

“These individuals are having difficulty affording food and housing, and so it’s a calculus: ‘Do I need health insurance? Do I think I’m going to have a catastrophic event or have some large health care expenditures this year?’” Nash says.

The government says about 8 in 10 of these eligible but uninsured people qualify for subsidies. But some of them will get only a little help from the government — since it is based on a sliding scale of income.

Other middle-income people would spend hundreds of dollars a month in premiums — and they wouldn’t qualify for the same help with out-of-pocket expenses that Thomas would. That means they could spend hundreds or thousands of additional dollars on a high deductible, if they need significant care.

Still, under the law, most people have to get insurance – or face a tax penalty next year of either 2.5 percent of income or $695 per adult and $347.50 per child under 18, with a maximum of $2,085. Even if people know about the penalties, they may not act. The fines for 2016 coverage don’t hit until Tax Day, 2017. And for many of people, that’s just too far away – and just too abstract.

This story is part of a reporting partnership that includes WNYC, NPR and Kaiser Health News.