BERKELEY, Calif. — Few people have the unusual set of professional experiences that Dr. Lonny Shavelson does. He worked as an emergency room physician in Berkeley for years — while also working as a journalist. He has written several books and takes hauntingly beautiful photographs.

Now, just as California’s law aid-in-dying law takes effect this week, Shavelson has added another specialty: A consultant to physicians and terminally ill patients who have questions about how it works.

“Can I just sit back and watch?” Shavelson asked from his cottage office. “This is really an amazing opportunity to be part of establishing policy and initiating something in medicine. This is a major change … [that] very, very few people know anything about and how to do it.”

Shavelson is the author of the 1995 book, “A Chosen Death,” which followed five terminally ill people over two years as they determined whether to amass drugs on their own and end their lives at a time of their choosing. He was present at the death of all of them.

He followed the issue closely for several years, but ultimately moved on to other projects — among them a book about addiction and a documentary about people who identify as neither male nor female.

The wall of Lonny Shavelson’s office, lined with covers of the books he has written. (Lisa Aliferis/KQED)

Then last fall came the surprising passage of California’s End of Life Option Act, giving terminally ill adults with six months to live the right to request lethal medication to end their lives. The law takes effect Thursday.

Shavelson decided he had to act, adding that he feels “quite guilty” about having been away from the issue while others pushed it forward.

His website, Bay Area End of Life Options, went up in April, and he’s outlined the law at “grand rounds” at several Bay Area hospitals this spring. His practice will be focused on consulting not only with physicians whose patients request aid-in-dying, but also with patients themselves. As he indicates on his site, he will offer care to patients who choose him as their “attending End-of-Life physician.”

Shavelson is adamant that this is “something that has to be done right.” To him, that means starting every patient encounter with a one-word question: “Why?”

“In fact, it’s the only initial approach that I think is acceptable. If somebody calls me and says, ‘I want to take the medication, my first question is ,’Why? Let me talk to you about all the various alternatives and all the ways that we can think about this.'”

Shavelson worries that patients may seek aid-in-dying because they are in pain. So first, he would like all his patients to be enrolled in hospice care.

“This can only work when you’re sure that the patients have been given the best end-of-life care, which to me is most guaranteed by being a part of hospice or at least having a good palliative care physician. Then this is a rational decision. If you’re doing it otherwise, it’s because of lack of good care.”

California is the fifth state to legalize aid-in-dying, joining Oregon, Washington, Vermont and Montana. The option is very rarely used. For example, in 2014 in Oregon, just 155 lethal prescriptions were written under the state’s law, and 105 people ultimately took the medicine and died.

Under the California law, two doctors must agree that a patient has six months or less to live. The patient must be mentally competent. At least one of the meetings between the patient and his or her doctor must be private, with no one else present, to ensure the patient is acting independently.

Patients must be able to swallow the medication themselves and must affirm in writing, within the 48 hours before taking the medication, that they will do so.

Shavelson says he has been surprised by the poor understanding of the law among some health care providers. One insisted the law was not taking effect this year; another asked how the law would benefit his patients with Alzheimer’s disease. (Patients with dementia don’t qualify under the law because they are not mentally competent.)

The law does not require that health care providers participate in ending terminally ill patients’ lives. Many physicians are “queasy” about the law, Shavelson said, and are unwilling to prescribe to patients who request the lethal medication — even when they think having such a law in place is the right thing to do.

“My response to that is as health care providers, you might have been uncomfortable the first time you drew blood. You might have been uncomfortable the first time you took out somebody’s gall bladder,” he said. “If it’s a medical procedure you believe in and you believe it’s the patient’s right, then it’s your obligation to learn how to do it — and do it correctly.”

Shavelson predicts that many physicians who are initially reluctant to provide this option to their patients may become more comfortable after the law goes into effect and they see how it works.

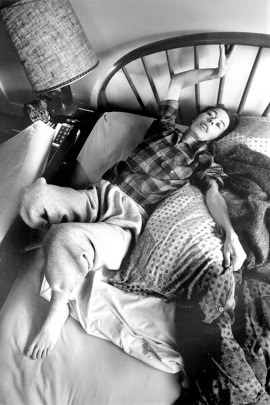

Renee Sahm, one of five terminally ill people followed by Lonny Shavelson in his 1995 book “A Chosen Death.” (Courtesy of Lonny Shavelson)

Burt Presberg, an East Bay psychiatrist who works with cancer patients and their families, attended a talk by Shavelson, and it led to some soul searching.

He wrestles with his own comfort level in handling patient requests. When he talks, he often pivots from his initial point to “on the other hand.”

Presberg says he is concerned that patients suffer from clinical depression at the end of life. Sometimes they feel they are a burden to family members who could “really push for the end of life to happen a little sooner than the patient themselves.”

His experience is that terminally ill patients with clinical depression can be successfully treated. He said he believes Shavelson will be aware of the need to treat depression,”but I do have concerns about other physicians.”

“On the other hand,” he added, “I think it’s really good that this is an option.”

Shavelson says he’s already received a handful of calls from patients, but mostly he’s spent his time before the law takes effect talking to other physicians. He needs a consulting physician and a pharmacist who will accept prescriptions for a lethal dose of medicine.

Then his mind returns to the patient. “It’s important … that we’re moving forward,” he said. “It’s crucial that we do that because this is part of the rights of patient care to have a certain level of autonomy in how they die.”

To him, this type of care “isn’t so tangibly different” from other kinds of questions doctors address.

“I’m just one of those docs who sees dying as a process, and [the] method of death is less important than making sure it’s a good death.”

This story is part of a partnership that includes KQED, NPR and Kaiser Health News.