Over the past few months, medical professionals on Chicago’s South Side have been trying a new tactic to bring down the area’s infant mortality rate: find women of childbearing age and ask them about everything.

Really, everything.

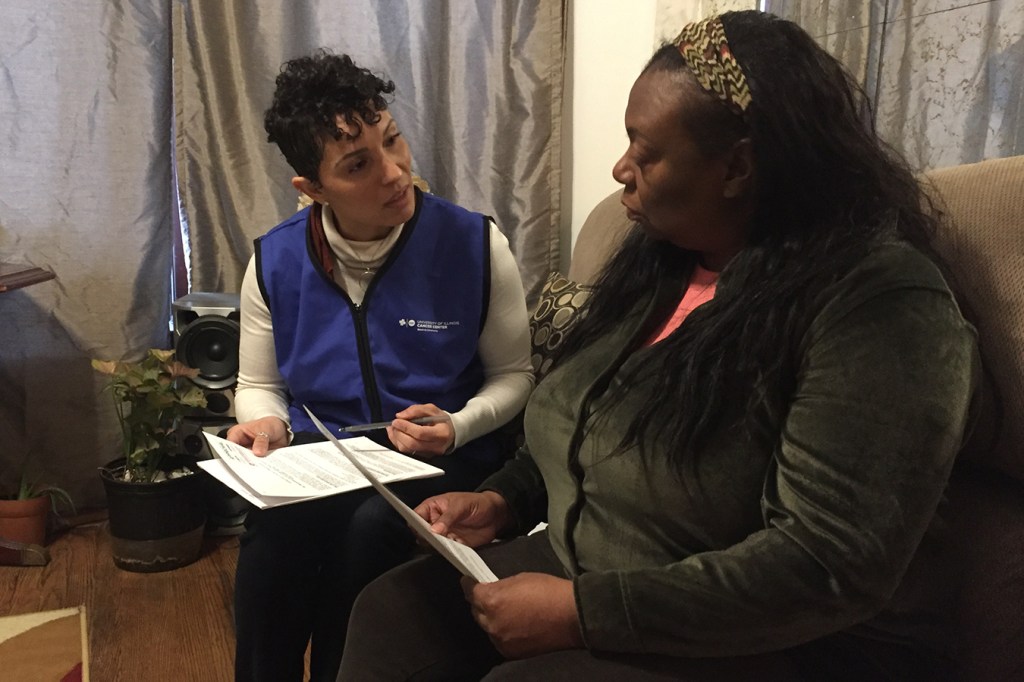

“In the last 12 months, have you had any problems with any bug infestations, rodents or mold?” Dr. Kathy Tossas-Milligan, an epidemiologist, asked Yolanda Flowers during a recent visit to her home, in Chicago’s Englewood neighborhood. “Have you ever had teeth removed or crowned because of a cavity?”

Though they seem to have little to do with motherhood, these questions are borrowed from the playbook of the Chicagoans’ new mentors — doctors from the Cuban Ministry of Public Health. As Tossas-Milligan administered her survey, two Cuban doctors sat nearby, observing.

Cuba, a poor country where many of the cars on the road are half a century old, may seem an unlikely role model for American health care. But its infant mortality rate, at 4.3 per 1,000, is lower than the United States’ 5.7 per 1,000, according to the World Health Organization’s 2015 data. And Cuba’s rate is much better than the infant mortality rates in some of the poorest parts of the U.S. In the Englewood neighborhood, for instance, 14.5 babies per 1,000 do not reach their 1st birthday. That’s a rate comparable to war-torn Syria.

Dr. Jose Armando Arronte-Villamarin, a doctor from the Cuban Ministry of Public Health, observes Yolanda Flowers’ interview with Dr. Tossas-Milligan. (Miles Bryan/WBEZ)

“Cuba is not a rich country,” said Dr. Jose Armando Arronte-Villamarin, one of the Cuban doctors. “[So] we have to develop the human resources, at the primary health care level.”

Now University of Illinois at Chicago health workers are bringing Cuban-style surveys and home visits to Englewood.

“Sometimes the answers are in the most unexpected places,” Tossas-Milligan said. “Sometimes it’s hard for us to face the reality that, as much as we spend, we have somehow not been successful at keeping our babies alive.”

The home visits came out of a partnership between the Cuban Ministry of Public Health and the University of Illinois Cancer Center. Three Cuban doctors and a nurse embedded in Chicago from August to December, joining their American counterparts in visiting the homes of 50 women of reproductive age in Englewood.

In exchange for a $50 stipend, the women answer dozens of questions, on topics ranging from the state of their home to their emotional well-being.

The project is funded by a $1 million grant from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, which has also paid for some American health care workers to visit Cuba.

In Chicago, researchers plan to use the data they gather to classify women into four risk groups. Those deemed at higher risk will be recommended for additional home visits. The idea, Tossas-Milligan said, is to address these women’s medical issues at an early stage and at home as much as possible, to avoid costly hospital bills.

“What we are hoping to discover is issues in Englewood that truly impact health, that are not being collected,” she said, “that the doctors cannot see when they come and see [a] woman, and prescribe her one pill.”

One question the team has been asking women for example, is when they last saw a dentist. Gum disease, while unlikely to come up during an expectant mother’s hospital visit, has been linked to premature birth.

In her interview, Yolanda Flowers said that she hadn’t been to a dentist “since 1999 or 2000,” which she attributed to a lack of insurance and a longtime fear of the dentist. And at 47, Flowers has had a difficult obstetric history: three miscarriages and one premature birth. Her baby did not survive.

Yolanda Flowers has had a difficult obstetric history: three miscarriages and one premature baby who didn’t survive. (Miles Bryan/WBEZ)

Flowers, who said she had “bare-bones insurance” or had been on Medicaid for much of her adult life, first attempted a planned pregnancy in 2003, with her then-fiancé. She visited a doctor who, Flowers recalled, suspected an ovarian cyst. But before they went further, Flowers’ fiancé died in an accident. In 2009, she tried to get pregnant again and visited a different doctor for help. That doctor, offered under a different health insurance plan, was not aware of her history, Flowers said, “because you only get a limited amount of time with the doctors, and there is only so much that I remembered.”

Tossas-Milligan and Arronte-Villamarin said that even if Flowers does not attempt another pregnancy, simply having that information, and having it in one place, could help them head off problems facing other potential mothers in the neighborhood.

The American health care workers would like to scale up this system to address other key health problems in underserved parts of the city.

Experts who have studied the Cuban health system say that is an idea worth exploring, but it would require much more than just home visits and health surveys.

“When a doctor or team [in Cuba] finds there problems in the home … and they think it has any bearing on her pregnancy, she gets help,” said Dr. Mary Anne Mercer, a senior lecturer emeritus at the University of Washington.

Mercer noted that Cuba, despite being very poor, guarantees resources for at-risk women.

By contrast, the Chicago effort may identify women in Englewood as needing food or different housing, but they would have to find a way to fill those needs on their own.

“Thinking about a very poor, low-income, disadvantaged setting in the U.S., I don’t think we’ve got those resources,” Mercer said. “So it’s nice to say, ‘Yeah, we could do it, if we were willing to expend those resources,’ but I am not convinced we could.”

“Would,” Mercer corrected. “I’m not convinced we would.”

This story is part of partnership with WBEZ and PRI’s The World.

KFF Health News' coverage of these topics is supported by Heising-Simons Foundation and The David and Lucile Packard Foundation