Small employers will more easily be able to band together to buy health insurance under rules issued Tuesday by the Trump administration, but the change could raise premiums for plans sold through the Affordable Care Act’s online marketplaces, analysts say.

The move loosens restrictions on so-called association health plans, allowing more businesses, including sole proprietors, to join forces to buy health coverage in bulk for their workers.

By effectively shifting small-business coverage into the large-group market, it exempts such plans from ACA requirements for 10 “essential” health benefits, such as mental health care and prescription drug coverage, prompting warnings of “junk insurance” from consumer advocates.

Supporters say the new Labor Department rules, which the government estimated could create health plans covering as many as 11 million people, will lead to more affordable choices for some employers.

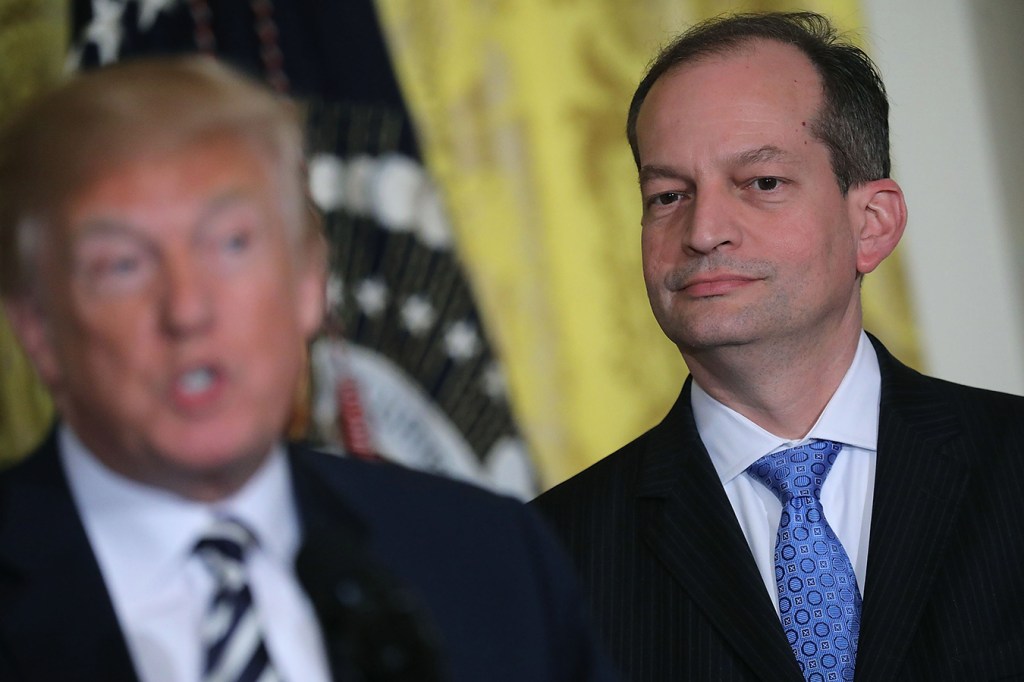

When it comes to health insurance, “the regulatory burden on small businesses should certainly not be more than that on large companies,” Labor Secretary Alexander Acosta told reporters Tuesday.

Existing rules limit association plans to groups of employers in the same industry in the same region.

The new regulations eliminate the geographical restriction for similar employers, allowing, for example, family-owned auto-repair shops in multiple states to offer one big health plan, said Christopher Condeluci, a health benefits lawyer and former Senate Finance Committee aide.

The rules, to be implemented in stages into next year, also allow companies in different industries in the same region to form a group to offer coverage — even if the only reason is to provide health insurance.

Like other coverage under the ACA, association insurance plans will still be required to cover preexisting illnesses.

Analysts warn that because these changes will likely siphon away employers with relatively healthy consumers from ACA coverage into less-expensive trade-association plans, the result could be higher costs in the online marketplaces.

“If you have a group that is healthier than average, you might get a better rate from one of these plans, and your broker is going to come and say, ‘Hey, I can get you a better deal,’” said Dan Mendelson, president of Avalere Health, a consulting firm.

That would mean that, on balance, consumers insured through ACA small-group and individual plans could be older, sicker and more expensive, adding to years of erosion of the ACA marketplaces engineered by Republicans hostile to the law.

Loosening rules for association plans would lead to 3.2 million people leaving the ACA plans by 2022 and raising premiums for those remaining in individual markets by 3.5 percent, Avalere calculated this year.

America’s Health Insurance Plans, the largest medical insurance trade group, issued a statement saying the regulation “may lead to higher premiums” in ACA insurance and “could result in fewer insured Americans.”

Unlike ACA plans, association coverage does not have to include benefits across the broad “essential” categories, including hospitalization and emergency care.

The National Association of Insurance Commissioners previously warned that such plans “threaten the stability of the small group market” and “provide inadequate benefits and insufficient protection to consumers.”

The American Academy of Actuaries has expressed similar concerns.

Business groups praised the change, proposed in draft form earlier this year.

“We’ve been advocating for association health plans for almost 20 years, and we’re pleased to see the department moving aggressively forward,” said David French, senior vice president of government relations for the National Retail Federation.

Association plans have been around for decades, although enrollment has been more limited since the ACA’s passage. While some of the plans have worked well for their members, others have a checkered history.

In April, for example, Massachusetts regulators settled with Kansas-based Unified Life Insurance Company, which agreed to pay $2.8 million to resolve allegations that it engaged in deceptive practices, such as claiming it covered services that it did not.

The coverage “was sold across state lines and was issued through a third-party association,” according to a release from the Massachusetts attorney general’s office.