Fresh off a political triumph in California, the nation’s chief advocacy group for physician-assisted suicide laws is mobilizing for many more battles on behalf of terminally ill patients.

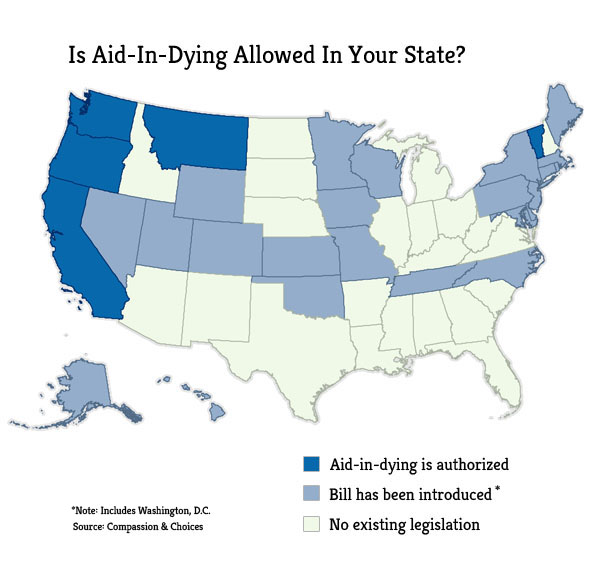

Since Gov. Jerry Brown signed California’s end-of-life options bill last month, a new chapter is starting for Compassion & Choices, a Denver-based nonprofit that led the campaign for the measure and has pushed for such laws for nearly 19 years. California is the fifth state, and largest by far, to allow physicians to prescribe lethal doses of drugs to patients who want to end their lives in their last stages of terminal illnesses.

Aid-in-dying bills were introduced this year in 23 state legislatures, plus in the District of Columbia, up from four last year, according to Compassion & Choices. Despite formidable opposition from the Catholic Church, disabled-rights groups and parts of the medical community, the group sees its strength growing.

Contributions and grants reached $17.1 million in the 2013-2014 fiscal year, more than double the previous five years’ average, its latest IRS filings on Charity Navigator show. A $2 million contribution from billionaire financier George Soros’ Open Society Foundations was the third largest from more than 50,000 donors.

Compassion & Choices’ volunteer force has tripled since mid-2014, numbering about 3,500 now, according to the group. The shift in statehouse sentiment is powered by polls measuring a sizeable boost in public support for doctors helping terminally ill patients die – 68 percent favored it in 2015, a 17-point swing in two years, according to Gallup.

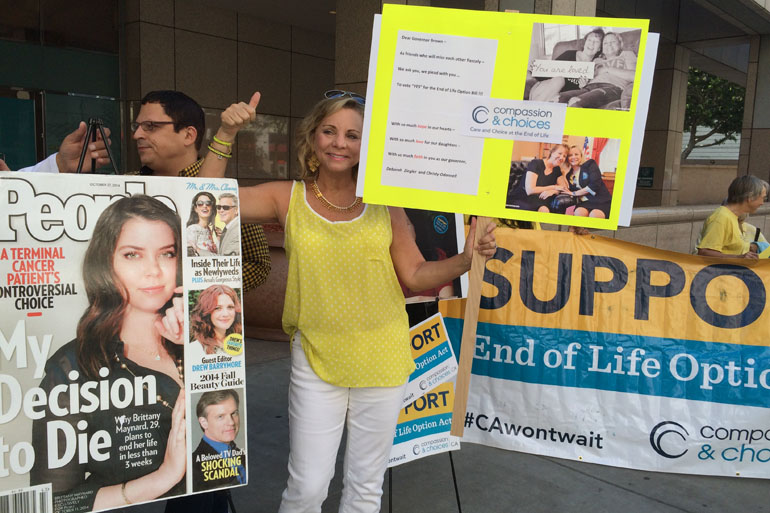

The polling firm credits the impact of the national spotlight on Brittany Maynard’s death one year ago on Nov. 1. A California newlywed with terminal brain cancer, Maynard chose to end her life on her terms in Oregon where the state allowed physicians to prescribe lethal drugs. Compassion & Choices connected with Maynard through a friend, and then worked to publicize her story, assisting in producing two widely-watched video interviews on YouTube and helping line up a People magazine article that put her on the cover shortly before her death at age 29.

Maynard spoke movingly about why she chose to control the timing of her death and spare herself and her family the added pain of waiting for a natural death. Her story put a compelling human face on an emotionally sensitive national debate that Compassion & Choices played an influential part in shaping.

“Brittany was young and full of life and saw her life horribly interrupted by brain cancer,” said Jessica Grennan, national political advocacy director for the group. “She could talk about what her wishes were and do so eloquently … and that really made everyone question what they wanted at the end of their life.”

Compassion & Choices is embracing that lesson as its campaign expands.

As more states take up the aid-in-dying issue, Grennan said her group will continue using individual stories to educate the public and lawmakers. In late October, Maynard’s husband, Dan Diaz, met with Massachusetts’ lawmakers and testified at a hearing in Boston. The New Jersey state senate is expected to vote on the issue in the next two months following last year’s approval in the state house.

California’s law is expected to take effect next year, but opponents hope to get enough signatures for a ballot initiative to overturn it next November.

Personal stories will continue to make the difference in getting lawmakers’ support, said Barbara Coombs Lee, the group’s president. “Individual stories are always what move people because they think ‘Oh, but for the grace of God, go I,’” Coombs Lee said. “We have been so fortunate to have the resources to take the charge Brittany gave us and use it to see new laws passed. … It has been nothing short of a miracle.”

In fact, Compassion & Choices campaigned hard to build support for the California law and then persuade legislators and Brown to back a bill. Compassion & Choices collected endorsements from several city councils, including Los Angeles, and submitted sympathetic opinion articles to major newspapers.

In addition to generating news coverage, the organization directed funds to California, too. In 2014 and 2015, it spent $150,000 on online advertising and other types of outreach, and $500,000 on focus groups, polling and other efforts to sway lawmakers and public opinion in the state, the group said.

Part of what Compassion & Choices has done is reframe the end-of-life debate on different terms. For instance, Catholic leaders have called laws such as California’s “assisted suicide” and argue that actively ending life is immoral and could cause some patients to die early for convenience of others.

“In a health care system grappling with constantly escalating costs, the elderly and disabled are in great peril now that assisted suicide has become legal,” the state’s Catholic bishops said in a statement on Oct. 5 after Brown signed the End-of-Life Option Act.

“In a health care system grappling with constantly escalating costs, the elderly and disabled are in great peril now that assisted suicide has become legal,” the state’s Catholic bishops said in a statement on Oct. 5 after Brown signed the End-of-Life Option Act.

In contrast, Compassion & Choices argues that “aid in dying” is the most neutral term to describe measures that some advocates call “death with dignity” and some opponents label “assisted suicide.” The group insists assisted suicide does not accurately describe terminally ill, but mentally competent, people who request life-ending medication that must be self-administered. The Associated Press Stylebook, widely used by news media, advises laws such as California’s be described as “medically assisted suicide” and allowing “the terminally ill to end their own lives with medical assistance.”

Coombs Lee has spearheaded lawmaking on behalf of the terminally ill for two decades. A former nurse turned attorney, she helped draft the ballot initiative that Oregon voters adopted to create the nation’s first aid-in-dying law in 1994. Since then, Compassion & Choices has helped win similar authorizations through ballot initiatives, legislation and court rulings in Vermont, Montana and Washington, in addition to California. New Mexico’s law is suspended while under review by the state’s highest court after conflicting decisions in two lower courts in 2014 and 2015.

The group Coombs Lee leads formed through a 2003 merger between two forerunners: Compassion in Dying, which Coombs Lee helped found in 1996, and the Hemlock Society founded in 1980.

With a unified front now on lobbying activities, Compassion & Choices counts 71 full-time employees, up from 46 in 2013, and, along with its Denver headquarters, keeps offices in California, Oregon, Montana and New Mexico. Compassion & Choices’ volunteers run phone banks, lead rallies and host parties to promote its side of the aid-in-dying debate. Its website invites people with end-of-life issues to share their stories there.

Nationally, health professionals are split on measures aiding people who wish to die. Physicians’ powerful lobbying group, the American Medical Association, remains opposed while the American Public Health Association, whose wider constituency includes public health policymakers, public health nurses and even restaurant inspectors, favors medically assisted suicide laws.

Despite social acceptance of hospice and palliative care for the terminally ill, both have their limits in controlling pain. Coombs Lee said people still have a need and the right to control how they die.

“What keeps me going all these years is knowing the comfort and peace of mind that giving people this option for aid in dying brings to people looking at death in the face,” she said. “Whether they fill the prescription or not and whether they ingest the medication or not just having the option gives them a sense of control.”

Barbara Feder Ostrov contributed to this story.