The high prices Americans pay for generic drugs may have been cooked up by pharmaceutical salespeople on golf courses, at a New Jersey steakhouse or over martinis at a “Girls Nights Out” in Minnesota.

Details emerging from an ongoing investigation show that drug company employees gathered regularly at such swanky locations and conspired to keep prices and profits high, according to interviews and a complaint filed last week in U.S. District Court by Attorneys General in 20 states.

“The wining and the dining and the dinners and the social repertoire sort of led to an atmosphere in which follow up conversations could occur [and] where price fixing could occur … because they had these relationships,” said Minnesota Attorney General Lori Swanson in an interview. “I think people should be absolutely appalled.”

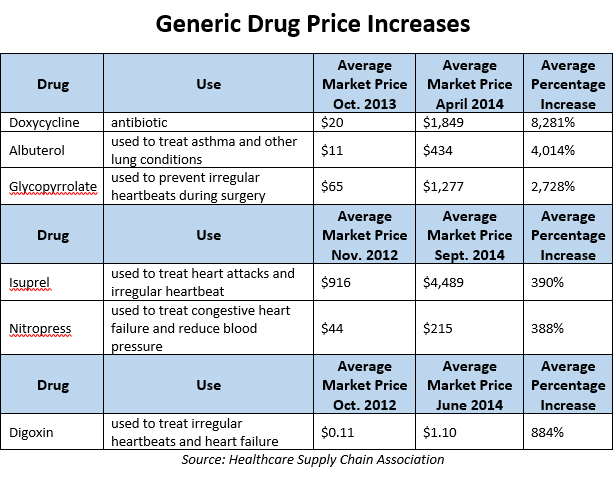

The lawsuit hits home for many middle-class families who have struggled in recent years to pay for generic medications while prices for some drugs soared more than 8,000 percent. The price for a decades-old antibiotic called doxycycline, for example, jumped from $20 for a bottle of 500 pills in October 2013 to more than $1,800 in April 2014.

That price hike was the result of secret efforts by generic drugmakers to make as much money as possible, the complaint says. Maine Attorney General Janet T. Mills said, “It is unconscionable for anyone to manipulate the system in order to line their pockets at the expense of people who need access to affordable medications in order to remain healthy.”

The ongoing Attorneys General investigation began in 2014, according to the complaint, and has “uncovered evidence of a broad, well-coordinated and long-running series of schemes.”

The companies accused of price fixing include Aurobindo Pharma USA, Citron Pharma, Heritage Pharmaceuticals, Mayne Pharma, Teva Pharmaceuticals USA and Mylan Pharmaceuticals, which has come under fire for an unrelated increase in the cost of its EpiPen, used for severe allergic reactions. The Justice Department also charged two former executives at Heritage with price fixing.

In addition to doxycycline, the companies and executives were charged with fixing the price of an oral diabetes drug called glyburide, which helps control blood sugar.

Spokeswomen for Teva and Mylan denied any wrongdoing. In a statement, Heritage said that it fired the two employees accused of price fixing in August and has filed a separate lawsuit against them, accusing them of embezzlement.

Spokeswomen for Teva and Mylan denied any wrongdoing. In a statement, Heritage said that it fired the two employees accused of price fixing in August and has filed a separate lawsuit against them, accusing them of embezzlement.

“We are fully cooperating with all aspects of the Department of Justice’s continuing investigation,” Heritage said. Aurobindo, Citron and Mayne did not respond to requests for interviews.

In an interview Friday, Connecticut Attorney General George Jepsen said, “The issues we’re investigating go way beyond the two drugs and the six companies. Way beyond … We’re learning new things every day.”

Generic drugs now account for 80 percent of prescriptions in the U.S., with sales of $74.5 billion in 2015. These drugs saved consumers $193 million in 2011 alone, because their prices are typically a fraction of the cost of brand-name drugs. Both consumers and taxpayers have been hurt by skyrocketing drug costs, according to the complaint. Medicaid plans spent more than $500 million from June 2013 to June 2014 on generic drugs whose prices more than doubled.

Generic drugmakers have explained recent price increases as the result of “a myriad of benign factors, such as industry consolidation, FDA-mandated plant closures or elimination of unprofitable generic drug product lines,” according to the complaint. In truth, the explanation for soaring prices is “much more straightforward and sinister — collusion among generic drug competitors,” the complaint said.

“It’s always suspicious when you see dramatic increases in price in areas where there’s really no market protection, either through patents or something else,” said Dana Goldman, director of the Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics at the University of Southern California.

Executives from Heritage, a New Jersey company described as the “principal architect and ringleader of the conspiracies,” sought out competitors and got them to “agree to raise prices for a large number of generic drugs,” according to the complaint.

A Heritage saleswoman from Minnesota would allegedly organize the Girls Nights Out, Swanson said. The gatherings were sometimes called “women in the industry” meetings, as if the aspiring executives intended to mentor each other on the secrets to getting ahead in a man’s world.

But the cozy cocktail conversation veered far from career advice. Instead, the saleswomen shared sensitive information about their companies’ business plans, according to the complaint.

Male drug industry executives weren’t idle, either. In 2014, at least 13 male CEOs, company presidents and senior vice presidents allegedly met at a steakhouse in Bridgewater, N.J. At these “industry dinners,” one company typically paid for dinner for all of the guests. Executives decided which company would pay based on alphabetical order. Drug company representatives socialized at trade shows, golf outings and conferences, as well, the complaint said.

Executives discussed how to divvy up market share to avoiding competing with each other for business, according to the complaint. Companies either declined to bid for certain customers or offered “cover bids” that they knew would be rejected. Companies knew they were breaking the law and took care to have most of these discussions on cell phones or in person, to avoid leaving a paper trail. Employees destroyed evidence from text messages and emails, the complaint said.

The issues we’re investigating go way beyond the two drugs and the six companies.

Heritage and other companies routinely consulted their competitors before selling new medications so that they could avoid competing on prices, the complaint said. The agreement gave the illusion of competition, but kept prices high.

In 2014, for example, Heritage “devised a scheme whereby it would seek out its competitors” and arrange to “raise prices for a large number of generic drugs,” including glyburide, whose price was targeted for a 200 percent increase, according to the complaint. Executives instructed the Heritage sales team to immediately contact competitors to agree on price increases.

Heritage executives destroyed incriminating emails, knowing that the company didn’t have a policy about keeping copies of old messages, according to the complaint. Employees involved in the scheme “deleted all text messages from their company iPhones regarding their illegal communications with competitors.”

“In August 2016, following an internal investigation that revealed a variety of serious misconduct by the individuals charged today, Heritage Pharmaceuticals terminated them,” the statement from Heritage said. “We are deeply disappointed by the misconduct and are committed to ensuring it does not happen again.”

Minnesota’s Swanson noted that some information in the complaint has been blacked out at the request of government officials. Eventually, though, Swanson said she wants all of the allegations’ details made public.

“I’m committed to try to see this through and have an unredacted copy of this complaint eventually get filed so people can see just what’s in all of these text messages an emails and what was occurring,” said Swanson. “I think that’s important.”

The investigation has uncovered a hidden side of the generic pharmaceutical industry, said Michael Carrier, a professor at Rutgers Law School who specializes in antitrust law in the drug industry. “It’s a bombshell,” he said.

The charges should prevent generic drugmakers from dramatically raising prices in the near future, Carrier predicted.

“These sorts of charges can filter out over months if not years,” Carrier said. Based on the complaint, he said, “it’s not just two bad apples acting alone.”

The victims of the alleged price fixing include both consumers and taxpayers, who support government insurance programs, the complaint said.

“Many Mainers rely on lower-cost generic prescription drugs in order to make ends meet,” said Mills.

The price fixing charges have surprised even pharmaceutical industry experts.

“There are some economic experts who have suspected that there is some tacit collusion among brand-name drugmakers not to lower drug prices,” said Dr. Hagop M. Kantarjian, chair of the department of leukemia at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, who has analyzed the strategies brand-name drugmakers use to keep their products out of the generic market. “But nobody has thought that possibly the generic companies could be potentially colluding to develop monopolistic prices.”

Kantarjian called for stiff penalties that drugmakers can’t write off as the cost of doing business. “If they’re guilty, they should be penalized in a deterrent fashion,” he said.

Goldman said drugs that have been used for years and cost pennies to make shouldn’t be regarded as ordinary consumer products.

“They should be thought of like electricity or something we all need,” Goldman said. “In electricity, we take the view that there is a safe and steady supply and we provide a fair return to the manufacturers.”

Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., and Rep. Elijah Cummings, D-Md., had asked Heritage for details about doxycycline’s price increase in 2014. In a letter to the company released Friday, they noted that Heritage never sent the information. When asked about the drug’s price increase, an attorney for Heritage told Cummings and Sanders that “Heritage has not seen any significant price increases” for doxycycline in the U.S.

In their new letter, Sanders and Cummings said Heritage’s 2014 statement now seems “disingenuous at best” and repeated their request for information about doxycycline’s sales and pricing.

KHN’s coverage of prescription drug development, costs and pricing is supported in part by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation.