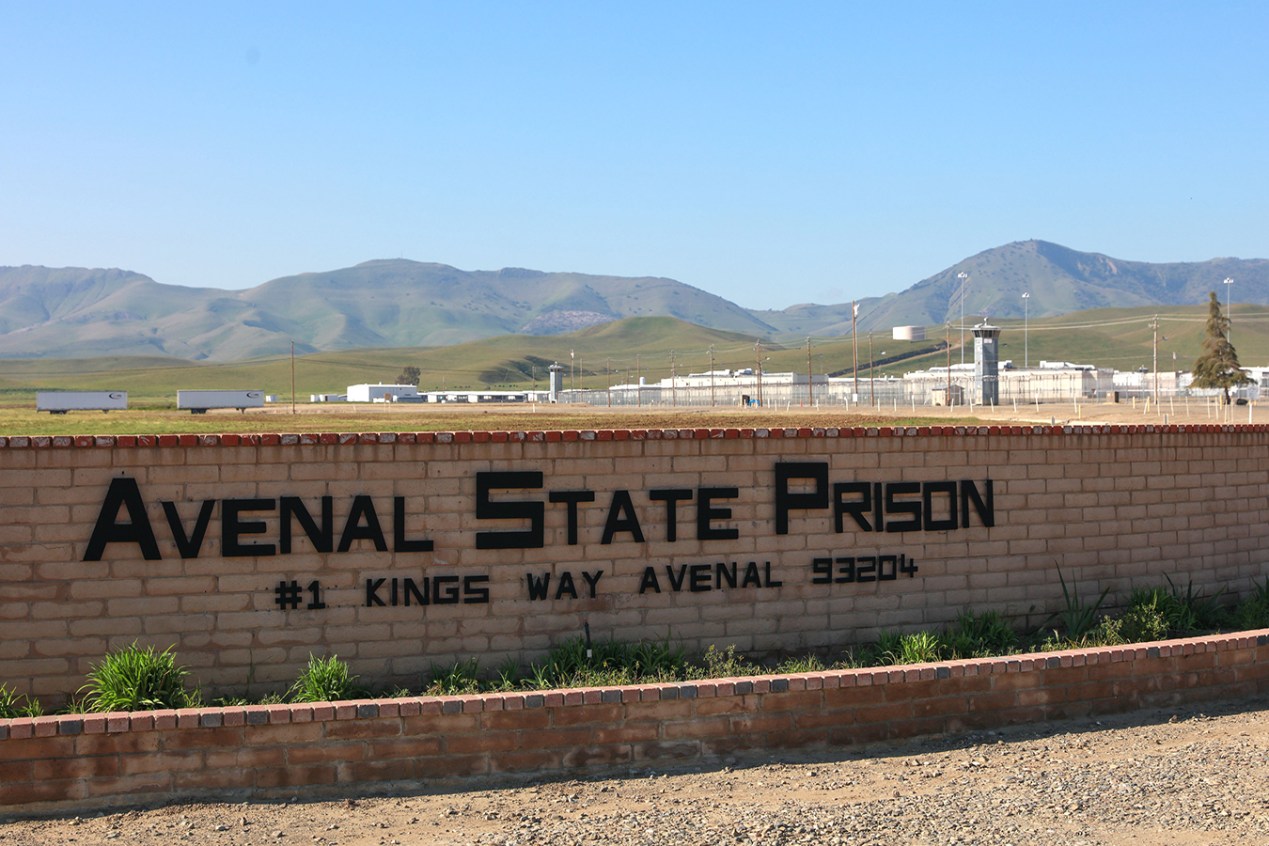

When news of the pandemic first reached the men incarcerated at Avenal State Prison in central California, inmate Ed Welker said the prevailing mood was panic. “We were like, ‘Yeah, it’s going to come in here and it’s going to spread like wildfire and we’re all going to get it,’” he said. “And that’s exactly what happened.”

Almost a year later, 94% of Avenal’s incarcerated men have contracted covid-19 and eight have died. With more than 3,600 confirmed cases among prisoners and staff members, the facility tops the list of the country’s largest covid clusters in prisons compiled by The New York Times and the UCLA Covid-19 Behind Bars Data Project.

Calling the prison system’s response to the pandemic “nonchalant,” “incompetent” and at times “negligent,” Welker and his fellow inmates described a crowded and dangerous living situation. Inmates interviewed by Valley Public Radio said physical distancing was nearly impossible, and constant moves in and out of quarantine were confusing and disruptive. The postponement of visits and rehabilitative programs left the men with little opportunity to vent their frustrations.

“It’s chaos over here, man,” said John Walker, 50, an inmate interviewed via the prison system’s collect-calling service during the fall surge in cases. “That’s why the mental health program’s blowing up.”

Similar grievances have been voiced by prisoners across the country, who have contracted the virus at a rate more than three times that of the general population, according to an analysis by The Associated Press and the Marshall Project, a nonprofit newsroom dedicated to the U.S. criminal justice system. Lawsuits and criminal justice advocates detail a pandemic response in prisons and jails that has ranged from careless to egregious.

California’s prison authority denies many of these men’s claims and instead points to the long list of precautions the agency has adopted since the pandemic began. Dana Simas, press secretary at the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, wrote in an email that state and Avenal officials “are continuously working with public health and health care experts to address this unprecedented pandemic and protect those who live and work in our state prisons.”

The virus continues to devastate prison populations and employees. Despite a dramatic drop in new infections since the holidays, more than 15,000 inmates nationwide have contracted the virus in the past three weeks, according to the Marshall Project. California’s facilities serve as a case study in which outbreaks recur while prison advocates argue that officials failed to enact a critical precaution: relieving overcrowding.

“There has not been the political will to do what’s necessary to keep people safe, which is to dramatically reduce prison and jail populations,” said Aaron Littman, a teaching fellow at UCLA School of Law and deputy director of the COVID-19 Behind Bars Data Project.

Early in the pandemic, corrections agencies across the country put in place measures to prevent outbreaks, mandating masks and physical distancing, setting aside housing units specifically for quarantined inmates, and establishing testing protocols for staffers and the incarcerated.

“The measures are important, the measures help … but those are not sufficient,” said Littman.

Horrific errors occurred. In late May, for instance, a transfer of a handful of inmates later discovered to have been covid-positive sparked an outbreak that killed 29 people and infected 2,600 others at San Quentin State Prison in Northern California.

Decision-makers disagree about what’s safe. At Avenal, as in all of California’s prisons, labor contracts permit guards to work different shifts in different buildings, despite the fact that many academic experts and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention discourage the practice.

The public health director of Kings County, where Avenal is located, tried to order the prison to temporarily freeze staff assignments in May, but the state prison authority politely informed him the county has no jurisdiction over a state-run facility. “The response to us was, ‘Well, because of labor agreements, we can’t do that,’” said Kings County Supervisor Craig Pedersen. “It was one of the most frustrating interactions we had, I think, in this process.”

Workplace culture may also undermine well-intentioned precautions. In a review published in October, California’s Office of the Inspector General, the state prison watchdog, reported that staff members failed to properly wear masks at two-thirds of the prisons it inspected. The report concluded lax enforcement was to blame.

Still, like Littman, many advocates and academics say preventive measures can accomplish little in such tightly packed environments. “Our review of the evidence indicates that relieving population pressures in jails, prisons, and detention centers greatly facilitates adherence to CDC guidelines, controlling COVID-19 outbreaks, and reducing health risks, particularly for medically vulnerable people,” members of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine wrote in an October report. “Smaller populations make it easier for correctional officials to place individuals in single cells, have sufficient resources for testing, and safely quarantine individuals after exposure to an infected person.”

When the pandemic began, 1.5 million inmates were housed in roughly 1,900 state and federal prisons, many of which were not just crowded but overcrowded. California’s prisons were stuffed with an average of 30% more inmates than they were designed to house. Avenal’s occupancy was nearly 50% beyond capacity.

Since March, the state corrections department has granted early releases to 19,000 inmates due to medical and other circumstances, but a federal judge argued it hasn’t been enough. “I have cajoled, begged and pleaded with the governor and the secretary to release a very significantly higher number of inmates beyond their current release efforts,” U.S. District Judge Jon Tigar said during a January hearing for an ongoing court case regarding medical care within the state’s prisons. “With all appreciation for the efforts they have made, those requests have fallen on deaf ears.”

It’s not just the incarcerated who are contracting covid at alarming rates. Throughout the country, nearly 103,000 prison employees have tested positive for the virus and 184 have died, a sum that doesn’t begin to account for the infections transmitted beyond prison walls to families and communities.

“It’s a huge concern,” said Jeff Garner, executive director of the nonprofit Kings Community Action Organization in rural Kings County, where three state prisons provide jobs for more than 4,300 people. “The prisons are a huge employer in our county. Whether it’s employees or clients, it’s kind of like those six degrees of separation.”

Just 40 miles from Avenal, on the other side of this agricultural county in the San Joaquin Valley, is the California Substance Abuse Treatment Facility and State Prison, Corcoran, ranked by The New York Times as the country’s second-largest cluster of covid in prison. Kings County health officials have not responded to multiple requests for comment about how these two prison outbreaks have contributed to community transmission of the virus.

Could the arrival of the vaccines finally put a stop to covid in prisons? In December, nearly 500 academics and public health experts signed a letter to the CDC calling for prisoners and correctional employees to receive priority access. At least nine states included incarcerated people in the first tier of vaccination plans, while 15 included prison staffers, according to the Prison Policy Initiative, a research organization that studies mass incarceration.

California began offering vaccines to medically vulnerable inmates at a limited number of facilities in December. By mid-February, the state had vaccinated close to 35,800 inmates and 24,900 correctional staffers.

Ed Welker, 58, hasn’t been offered a vaccine yet, but he said he’s not interested. Despite the 63 million doses that have already been shot into American arms, he’s wary of long-term side effects — and he also feels that, at Avenal, the vaccine is obsolete. “For this particular population, I think it’s a waste of time and money, because everybody here for the most part has had” covid, he said.

Although Welker said many inmates share his views, they appear to be in a minority: In a recent court filing, state officials reported that more than two-thirds of incarcerated people who’ve been offered the vaccine have accepted it.

Still, Welker argues that getting vaccinated, like masking and physical distancing, is a moral imperative for correctional staffers, who could bring the virus back to the prison. “They signed up for this,” he said. “It’s their job to protect us.”

Kerry Klein is a reporter with Valley Public Radio.

This story is from a reporting partnership that includes Valley Public Radio, NPR and KHN, an editorially independent program of KFF.