Thirteen year-old Natalie Giorgi probably didn’t know the name of the company that makes EpiPen. The 2013 death of the Sacramento girl from a peanut-induced allergy attack inspired passage of the California law that made the Mylan product a staple at every school.

It was Giorgi’s story, not industry lobbying, that then-California State Senate Minority Leader Bob Huff (R-San Dimas) said inspired him to usher through the requirement that public schools in the state stock the injectors. He said he was also influenced by one of his staffers who had a child with life-threatening allergies.

“It was just sort of organic,” said Huff about carrying the bill. “It seemed like we oughta do better to protect these kids.”

Mylan, the company that raked in $1 billion last year for the EpiPen, takes credit for passing “legislation in 48 states” to ensure schools have them. But its political maneuvering is only one reason the company has, in its own words, become “the number one dispensed epinephrine auto-injector.”

High-profile deaths in several states, particularly among school-age children, have helped to spur legislative action and fuel demand for consumer-dispensed epinephrine. At the same time, no other company has been able to effectively compete with Mylan’s drug-delivery device. Patent rules, and competitors’ manufacturing foibles, also have helped the company reign over the consumer epinephrine market.

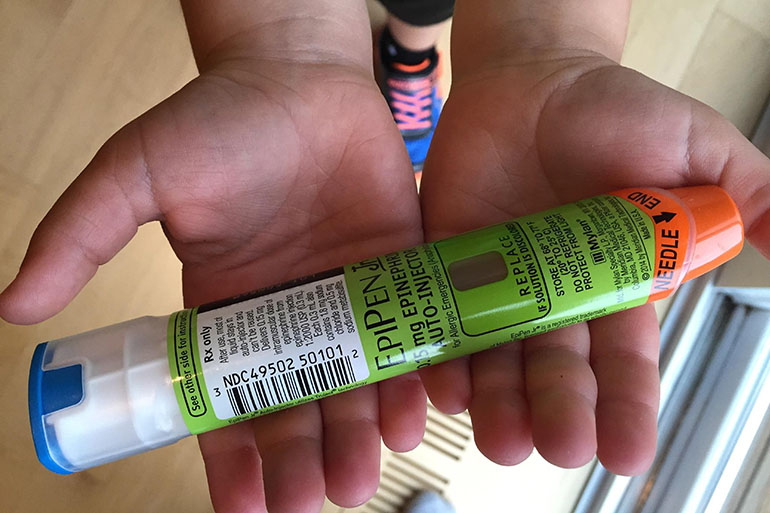

When someone with a severe allergy goes into anaphylactic shock and can’t breathe, “seconds count,” said Mylan CEO Heather Bresch in a recent CNBC interview about the EpiPen, which now has a sticker price of $608 per 2-pack. That’s why, she said, “they need to be everywhere.”

Bresch said lobbying is just one way the company has spent hundreds of millions “developing” the EpiPen since it acquired the patent in 2007.

Indeed, Mylan’s presence in state houses across the country has grown exponentially. The company added lobbyists in 36 states between 2010 and 2014, according to the Center for Public Integrity, outpacing every other U.S. company. And it spent more than $1.3 million lobbying in 16 states since 2012, according to the National Institute on Money in State Politics. (Those are not the exact states that passed the school requirements, however.)

Just in the past several years, 10 states have passed laws requiring epinephrine in schools. Another 38 states have passed laws permitting them, according to the Food Allergy Research & Education advocacy group (FARE).

Nebraska appears to have been the first state with a school epinephrine requirement. High asthma rates in the state, as well as a couple of school-based child fatalities due to the respiratory illness, created an emergency response protocol that became law in 2006.

In California’s case, Huff said he had never even heard of Mylan until the recent uproar over the EpiPen price increases. But the company is listed as a supporter of his bill, and FARE, partially funded by Mylan, was an official sponsor.

To address recent questions about its funding from Mylan, FARE announced Wednesday it would no longer accept money from epinephrine device makers until there’s “meaningful competition.” FARE asserts that the money it received from Mylan has helped fund its education work, not its advocacy.

It didn’t disclose exactly how much of its funding came from Mylan before Wednesday’s announcement, but said contributions from corporate partners amounted to less than 10 percent of its budget.

“In some states, momentum has been garnered by a fatality,” said Jennifer Jobrack, senior national director of Advocacy at FARE, who said local lawmakers and activists call them in for help to craft policy.

“Legislators are looking for something they know will have a positive impact,” Jobrack said.

Virginia’s law, passed in 2012, came after Amarria Johnson died at a Chesterfield County school from a reaction to peanuts. A Texas teenager’s death from fire ant bites led to that state’s law permitting epinephrine in schools.

President Barack Obama disclosed his daughter’s peanut allergy when he signed off on the 2013 federal “EpiPen law,” which gives financial incentives to states that require the medication in schools. Co-author of the federal legislation, Rep. Steny Hoyer, D-Md., cited his 11 year-old granddaughter’s peanut allergy when the EpiPen law passed the House. FARE and Mylan supported that effort as well.

With the help of these laws, Mylan’s EpiPens are at 63,000 schools nationwide and the company has distributed 500,000 of them for free through EpiPens4Schools.

New York State’s Attorney General announced Tuesday it will investigate Mylan to determine whether it introduced “anticompetitive terms” into school contracts. Stat recently reported that participants of Mylan’s EpiPen4schools program had to agree not to purchase EpiPen-like products for twelve months in order to get a discount.

The school give-away program brings visibility and credibility to the EpiPen brand, building a consumer base beyond schools.

“It’s kind of like the first hit’s for free,” said Nicholson Price, an assistant professor at the University of Michigan Law School. “You want to start people off with your product, and getting these products in at schools is a great way.”

Mylan also has a virtual monopoly on epinephrine auto-injectors simply because there are almost no other products like it, either branded or generic.

Mylan has a patent on the drug-device combo until 2025. If companies want to make a generic EpiPen, they have to sue Mylan in court to try to invalidate its exclusive rights on the injector, according to Jacob Sherkow, an associate professor at New York Law School.

Trying to create an EpiPen generic is an expensive and risky endeavor, said Sherkow. Even if a company is successful in court, manufacturing the device, which must be identical, is also challenging.

Copying a chemical compound, like ibuprofen, is easier than reproducing a piece of hardware, like the iPhone, said Sherkow. Patents are publicly available, and can act as an “instruction manual,” but a lot can go wrong in the actual production of EpiPen syringes.

“The drug inside can’t degrade or leak, they need to withstand shipping, they need to work at a wide range of temperatures, they need to be handled safely to not accidentally inject the user with the needle,” said Sherkow.

Teva Pharmaceuticals took on these challenges. It sued to invalidate Mylan’s patent in court so that it could make a generic version of EpiPen, and successfully got the green light to do so through a settlement agreement. But Teva has yet to win FDA approval to release the product.

Other companies have tried to make their own version of the epinephrine injector without attempting to copy the EpiPen. But their efforts haven’t been very successful either.

Amedra pharmaceuticals makes Adrenaclick, which has an injector with two caps (EpiPen only has one). But Amedra has limited manufacturing capabilities for the device and a barely visible market share, according to Price.

Auvi-Q, made by Sanofi, was taken off the market after concerns the device wasn’t dispensing the proper dose of epinephrine.

More epinephrine products will be on the market in 2017. Teva’s generic EpiPen is expected to be reintroduced then, and Mylan will put out its own generic in the coming weeks.

It’s too early to tell if more consumer choices will bring down EpiPen’s price.

This story was produced by Kaiser Health News, which publishes California Healthline, a service of the California Health Care Foundation.

Former Kaiser Health News intern Zhai Yun Tan contributed to this report.