Dr. Albert Hsiao and his colleagues at the University of California-San Diego health system had been working for 18 months on an artificial intelligence program designed to help doctors identify pneumonia on a chest X-ray. When the coronavirus hit the United States, they decided to see what it could do.

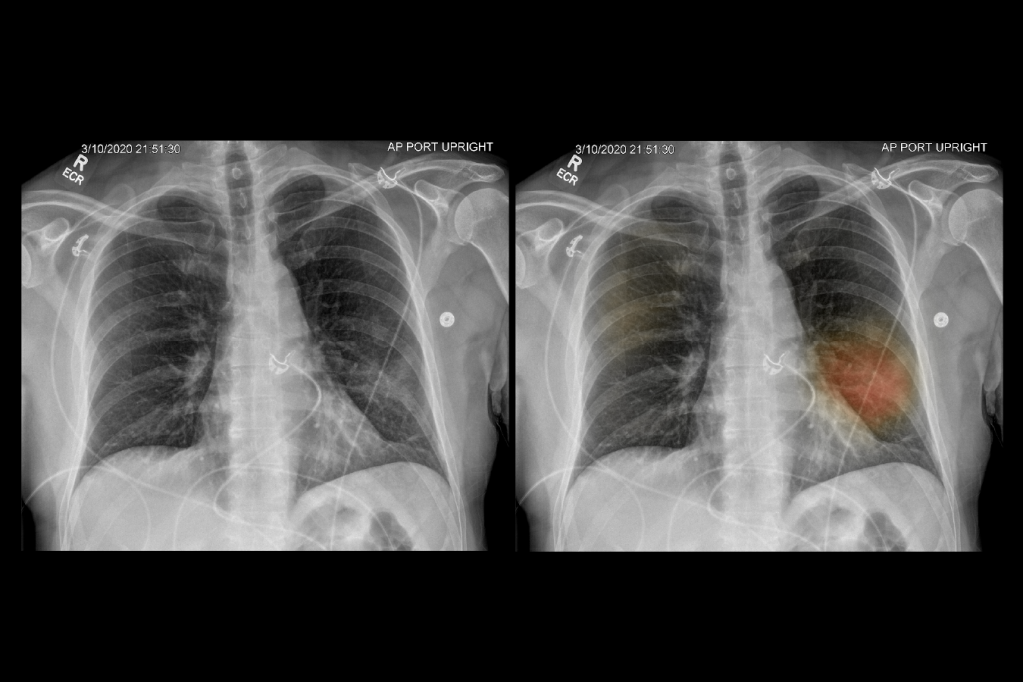

The researchers quickly deployed the application, which dots X-ray images with spots of color where there may be lung damage or other signs of pneumonia. It has now been applied to more than 6,000 chest X-rays, and it’s providing some value in diagnosis, said Hsiao, the director of UCSD’s augmented imaging and artificial intelligence data analytics laboratory.

His team is one of several around the country that has pushed AI programs developed in a calmer time into the COVID-19 crisis to perform tasks like deciding which patients face the greatest risk of complications and which can be safely channeled into lower-intensity care.

The machine-learning programs scroll through millions of pieces of data to detect patterns that may be hard for clinicians to discern. Yet few of the algorithms have been rigorously tested against standard procedures. So while they often appear helpful, rolling out the programs in the midst of a pandemic could be confusing to doctors or even dangerous for patients, some AI experts warn.

“AI is being used for things that are questionable right now,” said Dr. Eric Topol, director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute and author of several books on health IT.

Topol singled out a system created by Epic, a major vendor of electronic health records software, that predicts which coronavirus patients may become critically ill. Using the tool before it has been validated is “pandemic exceptionalism,” he said.

Epic said the company’s model had been validated with data from more 16,000 hospitalized COVID-19 patients in 21 health care organizations. No research on the tool has been published, but, in any case, it was “developed to help clinicians make treatment decisions and is not a substitute for their judgment,” said James Hickman, a software developer on Epic’s cognitive computing team.

Others see the COVID-19 crisis as an opportunity to learn about the value of AI tools.

“My intuition is it’s a little bit of the good, bad and ugly,” said Eric Perakslis, a data science fellow at Duke University and former chief information officer at the Food and Drug Administration. “Research in this setting is important.”

Nearly $2 billion poured into companies touting advancements in health care AI in 2019. Investments in the first quarter of 2020 totaled $635 million, up from $155 million in the first quarter of 2019, according to digital health technology funder Rock Health.

At least three health care AI technology companies have made funding deals specific to the COVID-19 crisis, including Vida Diagnostics, an AI-powered lung-imaging analysis company, according to Rock Health.

Overall, AI’s implementation in everyday clinical care is less common than hype over the technology would suggest. Yet the coronavirus crisis has inspired some hospital systems to accelerate promising applications.

UCSD sped up its AI imaging project, rolling it out in only two weeks.

Hsiao’s project, with research funding from Amazon Web Services, the University of California and the National Science Foundation, runs every chest X-ray taken at its hospital through an AI algorithm. While no data on the implementation has been published yet, doctors report that the tool influences their clinical decision-making about a third of the time, said Dr. Christopher Longhurst, UC San Diego Health’s chief information officer.

“The results to date are very encouraging, and we’re not seeing any unintended consequences,” he said. “Anecdotally, we’re feeling like it’s helpful, not hurtful.”

AI has advanced further in imaging than other areas of clinical medicine because radiological images have tons of data for algorithms to process, and more data makes the programs more effective, said Longhurst.

But while AI specialists have tried to get AI to do things like predict sepsis and acute respiratory distress — researchers at Johns Hopkins University recently won a National Science Foundation grant to use it to predict heart damage in COVID-19 patients — it has been easier to plug it into less risky areas such as hospital logistics.

In New York City, two major hospital systems are using AI-enabled algorithms to help them decide when and how patients should move into another phase of care or be sent home.

At Mount Sinai Health System, an artificial intelligence algorithm pinpoints which patients might be ready to be discharged from the hospital within 72 hours, said Robbie Freeman, vice president of clinical innovation at Mount Sinai.

Freeman described the AI’s suggestion as a “conversation starter,” meant to help assist clinicians working on patient cases decide what to do. AI isn’t making the decisions.

NYU Langone Health has developed a similar AI model. It predicts whether a COVID-19 patient entering the hospital will suffer adverse events within the next four days, said Dr. Yindalon Aphinyanaphongs, who leads NYU Langone’s predictive analytics team.

The model will be run in a four- to six-week trial with patients randomized into two groups: one whose doctors will receive the alerts, and another whose doctors will not. The algorithm should help doctors generate a list of things that may predict whether patients are at risk for complications after they’re admitted to the hospital, Aphinyanaphongs said.

Some health systems are leery of rolling out a technology that requires clinical validation in the middle of a pandemic. Others say they didn’t need AI to deal with the coronavirus.

Stanford Health Care is not using AI to manage hospitalized patients with COVID-19, said Ron Li, the center’s medical informatics director for AI clinical integration. The San Francisco Bay Area hasn’t seen the expected surge of patients who would have provided the mass of data needed to make sure AI works on a population, he said.

Outside the hospital, AI-enabled risk factor modeling is being used to help health systems track patients who aren’t infected with the coronavirus but might be susceptible to complications if they contract COVID-19.

At Scripps Health in San Diego, clinicians are stratifying patients to assess their risk of getting COVID-19 and experiencing severe symptoms using a risk-scoring model that considers factors like age, chronic conditions and recent hospital visits. When a patient scores 7 or higher, a triage nurse reaches out with information about the coronavirus and may schedule an appointment.

Though emergencies provide unique opportunities to try out advanced tools, it’s essential for health systems to ensure doctors are comfortable with them, and to use the tools cautiously, with extensive testing and validation, Topol said.

“When people are in the heat of battle and overstretched, it would be great to have an algorithm to support them,” he said. “We just have to make sure the algorithm and the AI tool isn’t misleading, because lives are at stake here.”

This story was produced by KFF Health News, which publishes California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation.