With federal spending on Medicaid experiments soaring in recent years, a congressional watchdog said state and federal governments fail to adequately evaluate if the efforts improve care and save money.

A study by the Government Accountability Office released Thursday found some states don’t complete evaluation reports for up to seven years after an experiment begins and often fail to answer vital questions to determine effectiveness. The GAO also slammed the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services for failing to make results from Medicaid evaluation reports public in a timely manner.

“CMS is missing an opportunity to inform federal and state policy discussions,” the GAO report said.

Joan Alker, executive director of the Georgetown University Center for Children and Families, called the report’s findings “troubling but not surprising.”

“It has been clear for some time that evaluations of Section 1115 waivers are not adequate,” she said. “There is some good work going on in this space at the state level, for example in Michigan and Iowa, but as the report makes clear state’s evaluations are often incomplete and not rigorous enough.”

These experiments are often called “demonstration projects” or “1115 demonstration waivers” — based on the section of the law that allows the federal government to authorize them. They allow federal officials to approve states’ requests to test new approaches to providing coverage. They are used for a wide variety of purposes, including efforts to extend Medicaid to people or services not generally covered or to change payment systems to improve care.

Medicaid demonstration programs often run for a decade or more. Several states that expanded Medicaid eligibility under the Affordable Care Act did so through a demonstration program, including Indiana, Iowa, Arkansas and New Hampshire.

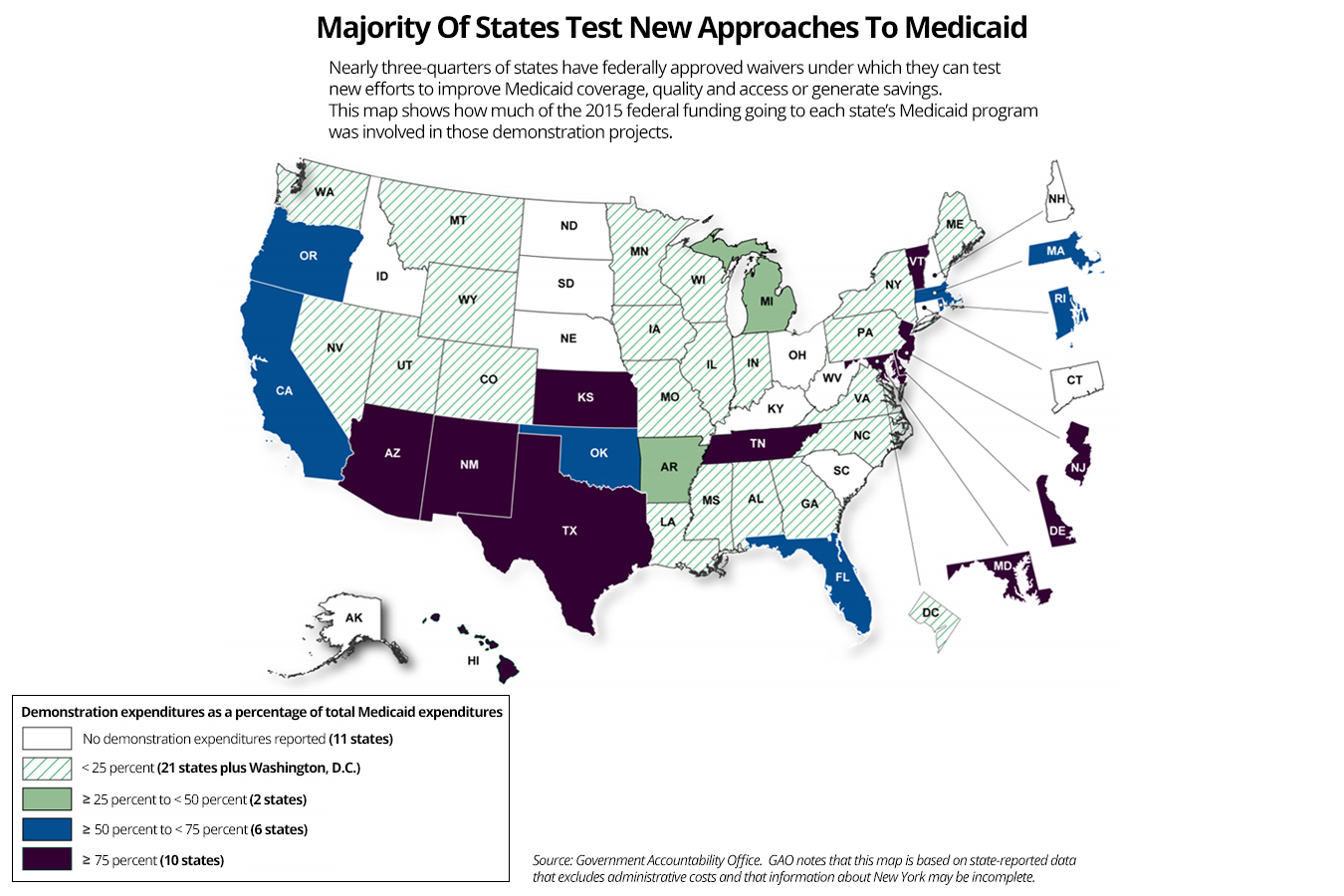

Nearly three-quarters of states have Medicaid demonstration programs, such as those testing providing services through private managed-care firms and requiring enrollees to pay monthly premiums. About a third of the federal government’s $300 billion a year in Medicaid spending goes to these test programs, the GAO said.

The study, requested by top GOP lawmakers including Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-Utah), reviewed demonstration programs in eight states — Arizona, Arkansas, California, Indiana, Kansas, Maryland, Massachusetts and New York.

In five of these states, money from their Medicaid demonstration program makes up more than half their total federal Medicaid budgets. Nearly all of Arizona’s funding — 99.7 percent — is through a demonstration program.

The use of Medicaid demonstration programs accelerated during the 1990s. But in recent years the experiments have often reflected the political leanings of state officials or the party controlling the White House. Under a demonstration program, the Trump administration this year approved requests from Indiana and Kentucky to enact work requirements for some adult Medicaid enrollees.

The GAO report noted that states often do not complete their evaluation reports until after the federal government renews their demonstration program. For example, Indiana’s Medicaid expansion demonstration program, which charges premiums and locks some enrollees out of coverage for lack of payment, was renewed in February even though a final evaluation report is not yet complete.

GAO said Indiana’s evaluation of its Medicaid expansion won’t look at the effect of the state’s provision that locks out enrollees for six months if they fail to pay premiums.

“GAO found that selected states’ evaluations of these demonstrations often had significant limitations that affected their usefulness in informing policy decisions,” the report said.

Alker said that “more sunshine and data are needed” to assess waivers, “especially as they are clearly the vehicle the Trump administration is now using to pursue its ideological objectives for Medicaid.”

(Story continues below.)

While states typically contract with independent groups to evaluate Medicaid demonstration programs, the federal government sometimes does its own review.

But the GAO investigators found Indiana’s Medicaid agency wasn’t willing to work with the federal contractor out of privacy concerns. That halted efforts for a federal review.

Joel Cantor, director of the Center for State Health Policy at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, N.J., said the demonstration programs have often shifted from their intended purpose because they are designed by lawmakers pushing an agenda rather than as a scientific experiment to find better ways to deliver care.

“Demonstration programs have been used since the 1990s to advance policy agenda for whoever holds power in Washington and not designed to test an innovative idea,” he said.

The evaluations often take several years to complete, he said, because of the difficulty of getting patient data from states. His center has done evaluations for New Jersey’s Medicaid program.

GAO recommended that CMS require states to submit a final evaluation report after the end of the waiver period, regardless of whether the experiment is being renewed, and that the federal agency publicly release findings from federal evaluations in a timely manner. Federal officials said they agreed with the recommendations.

Matt Salo, executive director of the National Association of Medicaid Directors, said the report highlighted a need to modernize the law dealing with Medicaid so that successful experiments are quickly incorporated into the overall program.

“The underlying problem is that the Medicaid statute has fundamentally failed to keep up with the changing reality of health care in the 21st century,” he said. “There’s no way to update the rules to make these changes” a permanent part of the program.