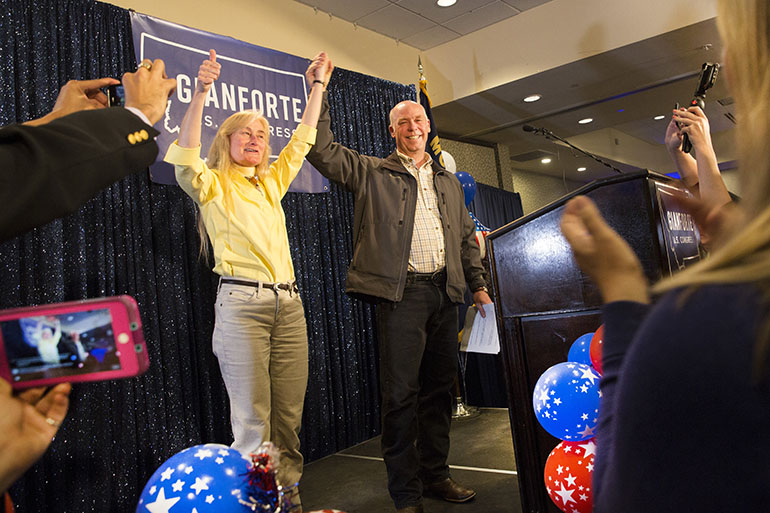

There was likely good reason why Greg Gianforte, successful Republican candidate for Congress from Montana, lost his cool on the eve of the election — scuffling with a reporter, breaking the man’s glasses and ending up with a misdemeanor assault charge:

He, like many Republicans these days, walks a perilous line when talking health care.

Ben Jacobs, a reporter for The Guardian, approached the candidate armed with an audio recorder and persistent, pesky questions about a Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report, which found that the GOP’s American Health Care Act would leave 23 million more Americans uninsured over 10 years and would effectively price out from coverage millions with preexisting conditions.

Though the AHCA passed muster in the House of Representatives, disapproval of the Republican plan has been high among voters — by ratios of more than 2-to-1 among men and more than 3-to-1 among women, according to a Quinnipiac University poll. Over 50 percent of Republicans opposed cutting federal funding for Medicaid, a component of the bill.

Torn between conflicting impulses, the GOP candidate for Montana’s only seat in the House of Representatives had already stepped into the health care muck twice — on opposite sides of the issue. He told reporters he would not have voted for the Obamacare repeal bill passed by the House earlier this month, but a tape surfaced of him saying he was “thankful” for that same bill during a fundraising call with D.C. lobbyists. No wonder he wasn’t eager to respond to Jacobs’ question.

On the other side of the political divide, Democratic challenger Rob Quist tried to seize the moment, making opposition to the AHCA a campaign issue. On the final weekend before Thursday’s vote, Quist made a major buy of political ads that pinned the erosion of preexisting condition protections on his opponent. He confided his own preexisting condition — related to “a botched gall bladder surgery” — and noted that about half of all Montanans have a preexisting condition. Approximately 52 million Americans have a health history that could make them uninsurable in the future, if laws don’t guard against the practice.

According to the CBO report, “people who are less healthy (including those with preexisting or newly acquired medical conditions) would ultimately be unable to purchase comprehensive nongroup health insurance at premiums comparable to those under current law, if they could purchase it at all.”

Quist’s health narrative also dissolved one of Gianforte’s most potent attacks on him: financial problems that led to bankruptcy. Medical bills caused that bankruptcy, Quist said, and indeed, as a folk singer for most of his life, Quist was someone who had to buy health insurance on the unstable and discriminatory individual market. At 69, he can now rely on Medicare.

Gianforte, at 56, is in the age range of those who can be charged five times more than younger people for insurance under the House-passed bill. But, like President Donald Trump, Gianforte is a wealthy businessman, who likely has not had to focus deeply on the high costs of health coverage.

The altercation may not have affected the election. The seat has been occupied by a Republican for more than two decades, and nearly two-thirds of the expected turnout had already cast a ballot by mail. Montana also has same-day voter registration. Reporters from Montana Public Radio heard from brand-new voters Thursday — some who were appalled and compelled by Gianforte’s behavior and others who thought Jacobs was in the wrong.

It’s hard to say how much health care influenced Gianforte’s 6 percentage point win over Quist. The use of public lands had been the central issue in the election, and both candidates had avoided the topic of health care for much of the race, which replaces the seat vacated by Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke.

But Gianforte’s election eve scuffle may signal how tense and explosive health care will be politically for the 2018 election cycle.

Eric Whitney of Montana Public Radio contributed to this report.