Brian and Sandy Willhite (Courtesy of the Willhite family)

Sandy Willhite doesn’t mind driving 45 minutes to the nearest shopping center. But living in Hillsboro, W.Va., became problematic when she had to travel nearly six hours for proper foot treatment.

“There just aren’t any quality surgeons or specialists in our area,” Willhite said, when explaining why she went to a doctor in Laurel, Md.

Getting health care is a common problem for the residents of Hillsboro, a tiny hamlet in the middle of Appalachia with a population of just under 250 residents.

And the Appalachian region is in dire need of health care. This section of the U.S., long acknowledged to be among the most economically disadvantaged in the country, is showing a growing gap in health outcomes with the rest of the United States.

A study released Monday in the journal Health Affairs found disparities widening sharply between Appalachia and the rest of the country, driven by higher rates of infant mortality, smoking, obesity and early deaths from motor vehicle accidents and drug overdoses.

“Although life expectancy increased everywhere in the United States between 1990 and 2013, less rapid declines in mortality and slower gains in life expectancy among people in Appalachia have led to a widening health gap,” the study said.

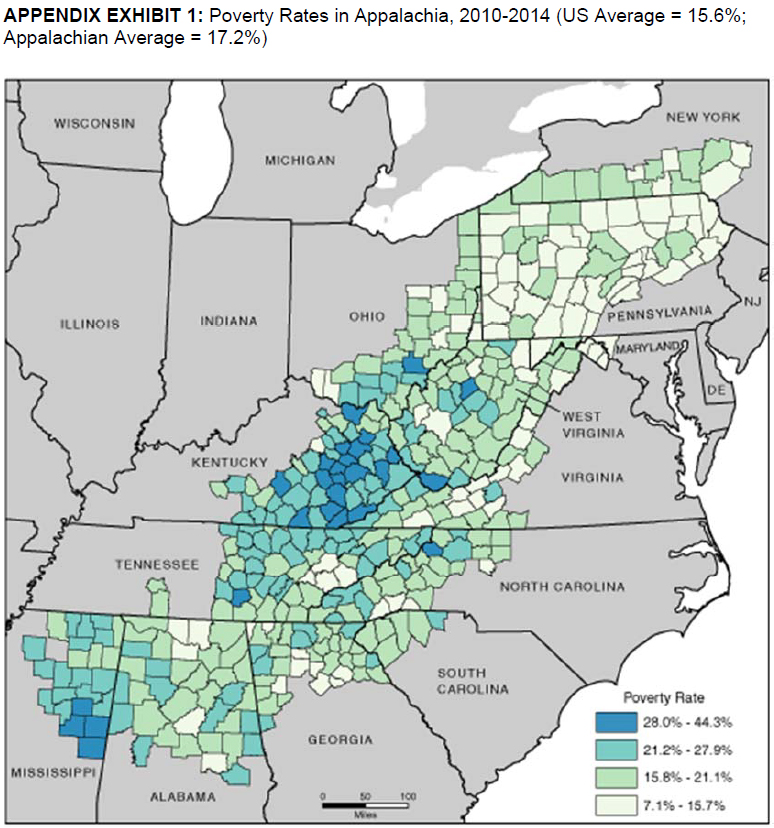

The study focused on the 428 counties within the 13 states that constitute Appalachia. Gopal Singh, an author of the study and a senior health equity adviser at the Health Resources and Services Administration, found that counties with high rates of poverty have the highest infant mortality rate and lowest life expectancy. These areas are seen mostly in central and southern Appalachia.

Courtesy of Health Affairs

The researchers found Appalachia lagged behind the rest of the country on health measures in the early 1990s — but only slightly. Infant mortality rates were not statistically different. And life expectancy was about 75 years — just 0.6 years shorter than that outside of the region.

But when the researchers analyzed data from 2009 to 2013, they found the infant mortality rate for Appalachia to be 16 percent higher than the rest of the country and the difference in life expectancy was 2.4 years.

When researchers examined specific demographic groups, some of the disparities were much greater. For instance, they noted a 13-year gap in life expectancy between black men in high-poverty areas of Appalachia (age 70.4) and white women in low-poverty areas elsewhere in the country (83).

According to the study, the association between poverty and life expectancy was stronger in Appalachia than the rest of the country.

“You do see a more rapid improvement in the rest of the country compared to Appalachia, but there are specific reasons why Appalachia I guess continues to fall behind,” said Singh, the lead author.

The study points to specific health problems, including lack of access to doctors and other providers, high rates of preterm births and low-weight births, and high rates of smoking-related diseases, such as lung cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and heart disease.

“Smoking-related diseases accounted for more than half of the life-expectancy gap between Appalachia and the rest of the country,” the study said.

Dr. Joanna Bailey treats some of Appalachia’s patients every day as a family medicine physician in Wyoming County, W.Va. She grew up there and said the lifestyle plays a large role in health outcomes. “I treat a lot of diabetes; I see a lot of high blood pressure; I see a lot of heart disease. I see a lot of obesity, because it is a place where it has been normalized quite a bit.”

“I think that the culture is such that getting those conditions under control is difficult for many reasons,” Bailey said.

The economic issues compound the situation, she said.

“There’s the problem of poverty,” she added. “A lot of people are on disability and they rely on food stamps to get their food for the month.” Many of Bailey’s patients pay someone to drive them to the grocery store. She said it’s difficult to coach them to buy healthful groceries when the food is good only for a few days.

“By the end of the month, they are back to eating cereal and Hamburger Helper,” Bailey said.

She thinks the widening health gap in recent years has accelerated with an increasing number of young people leaving the area for job opportunities.

“We’re left with an older, sicker population who can’t work or don’t work, and those people are notoriously sicker,” Bailey said.

Both Bailey and Singh agree that addressing the health gap requires socioeconomic change. The communities need better higher-education opportunities and infrastructure improvements, such as improved roadways so patients can more easily get to larger towns and cities to access health care.

Until then, Willhite and her family will continue to drive hours for care, such as the foot doctor in Laurel, whom she had consulted when she lived in Maryland.

“There are just absolutely so many (health) issues here in this region, you can’t begin to put your finger on one,” Willhite said. “It’s like a big vicious circle.”