Doctors should consider expensive new hepatitis C drugs for patients with advanced liver disease, including those awaiting transplants, but ask most others to wait for drugs in development, the Department of Veterans Affairs said Wednesday.

A California panel made similar recommendations Monday, saying in a report to insurers, providers and consumers that immediate treatment with the new drugs, Sovaldi and Olysio, should be given to those with advanced disease, but could be delayed for others.

Limiting the number of patients treated with the drugs may prove controversial but necessary because the costs per patient can run from $70,000 to $170,000, and there may be too few specialists to handle a sudden influx of patients, according to the report from the California Technology Assessment Forum. An estimated 3 million Americans have hepatitis C.

“We think these drugs should be used because they have a high clinical benefit, but not everyone needs to be treated immediately,” said Rena Fox, a professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, who was one of 10 experts for the VA who drafted “treatment considerations” after a review of the drugs’ effectiveness.

The findings of the two expert panels come amid controversy over the high cost of the drugs, which could potentially cure large numbers of people with the hepatitis C virus, many of whom are in taxpayer-supported programs such as the VA, Medicaid and state and federal prisons. Although some medical groups have made initial recommendations for the drugs’ use, these are the first large-scale efforts to consider which patients should be treated first.

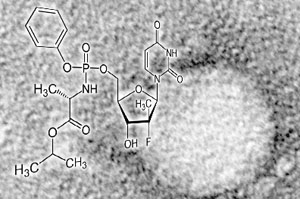

The drugs cost as much as $1,000 a pill and are often used in combination with other drugs such as interferon and ribavirin, which can have debilitating side effects. Still, for some patients, the effectiveness can be greater than 90 percent, an improvement over earlier treatments.

What’s A Cure Worth?

Drugmakers Gilead and Janssen Therapeutics say the medications’ prices are justified because they cure many people and prevent the need for costly medical care by those with the slow-advancing infection.

The VA report, while aimed mainly at helping VA doctors choose which patients should get treatment immediately, could also influence private insurers setting their guidelines.

“If these were a penny a tablet, we would want to treat everyone,” said Fox. “But for the time being, we have only a certain number of hepatologists out there with experience using these drugs and we cannot treat the whole population.”

Other drugs now in development, which could be used without interferon, might be available as early as this fall.

Hepatitis C is a blood-borne infection which generally progresses slowly, leading to symptoms in at least 70 percent of patients over time, often decades. If left untreated, it may cause chronic liver disease in 60 to 70 percent of patients and lead to death from cirrhosis or liver cancer in 1 to 5 percent, according to the California report.

The virus is spread mainly by intravenous drug use. But many people were unknowingly infected by poorly sterilized medical equipment and blood transfusions before widespread screening of the blood supply began in 1992. Some may also been infected through tattoos and piercings with contaminated needles.

VA officials did not return calls about whether the agency would cover Sovaldi and Olysio for patients who have no symptoms or have only mild liver disease.

In January, two physician groups recommended treatment for nearly all patients. However, that report from the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease and the Infectious Diseases Society of America did not specify which patients may be able to rely on older treatments or wait for new drugs.

“We make recommendations we think are in the best interests of patients,” said Donald Jensen, a co-chair of the specialty society guideline committee and director of the Center for Liver Diseases at the University of Chicago. “For most patients, the newer drugs – even if used with interferon and ribavirin — have advantages over previous therapies.”

The VA report shows that many patients with various types of hepatitis C could benefit from treatment. Even so, evidence for the drug’s effectiveness for some groups is weak, Fox said.

For example, a combination of Sovaldi and Olysio, is sometimes used for patients with the most common type of hepatitis C — genotype 1 — who can’t take interferon. But studies of the effectiveness of that regimen have been done on only a small set of patients and are not yet final. The Food and Drug Administration has not approved the combination either.

“The data are scant,” said Fox, “so if patients are not in an urgent situation, we would advise them to consider waiting either until there is better data, or other options.”

It isn’t unusual for patients with hepatitis C to delay treatment because interferon was included in many regimens and is so difficult to take. Many are also expected to wait until more interferon-free choices are available, experts say.

“It’s not unreasonable for payers to figure out ways not to treat everyone,” said Steve Pearson, who oversaw the report by the California Technology Assessment Forum, which is funded by the Blue Shield of California Foundation. “There will be other drugs available soon that may be even better.”

The 15-member California panel, which includes doctors, consumer advocates and research experts, voted last month that the new drugs, while an advance over older treatments, represented “low value” that given their price, as part of deliberations leading up to this week’s report.