Faced with the possibility that a bout of abnormal heartbeats could end his life, in 2006, Dr. Marc Sicklick had a small device implanted in his chest that would shock it back into rhythm. Soon he would struggle with another life-or-death choice: whether to remove the Sprint Fidelis, which was deemed dangerous and recalled in 2007 after it had been implanted in hundreds of thousands of patients.

The Sprint Fidelis was prone to giving patients random electrical jolts — and sometimes failed to fire in genuine cardiac emergencies, according to manufacturer Medtronic’s letter to doctors.

What Sicklick and thousands of others in his position have not known is that the Food and Drug Administration quietly took steps to keep critical information out of the public light. Shortly after the recall, the FDA and Medtronic made a deal to keep reports about the widely used device’s malfunction incidents — now totaling 50,000 — shielded from public scrutiny.

The FDA has allowed device makers to file 1.1 million reports of injuries or malfunctions to a little-known internal FDA database since 2016, a recent Kaiser Health News investigation has found, spurring top FDA officials to pledge to open those records within weeks and shut down the “alternative summary reporting” program.

For the past two decades, the agency has granted various devices different types of so-called exemptions from reporting to their public-facing database, called MAUDE, KHN has found.

One of those exemptions covered the Sprint Fidelis. In May 2008, it was granted a “remedial action” exemption — allowed when “the manufacturer has initiated reasonable and appropriate actions to mitigate the problem(s)” and further reports of harm will not “provide any significant new data,” FDA spokeswoman Deborah Kotz said in an email. She said the FDA hasn’t granted such an exemption since 2015 and has “effectively ended the program,” and could not say whether that data would be opened to the public soon.

The logic of the FDA’s approach sits poorly with patients like Sicklick who have a Sprint Fidelis buried deep in their chests. “Worrying about it not working [has] caused a tremendous, tremendous amount of anxiety in me, and I’m not an anxious person,” said Sicklick, an allergy specialist from Long Island, N.Y. “I think the FDA should be making this information public.”

Six top cardiologists interviewed for this report said they weren’t aware the FDA had granted Medtronic such an exemption.

“Amazing. Really amazing,” said Dr. Robert Hauser, the Minnesota cardiologist whose research first brought the high rate of Sprint Fidelis failures to light. “It’s not in the best interest of the patients who have these devices.”

Hauser and other doctors have spent years helping patients navigate the risks of living with a cardiac implant that could harm them or undergoing a complicated device-removal surgery that could prove deadly.

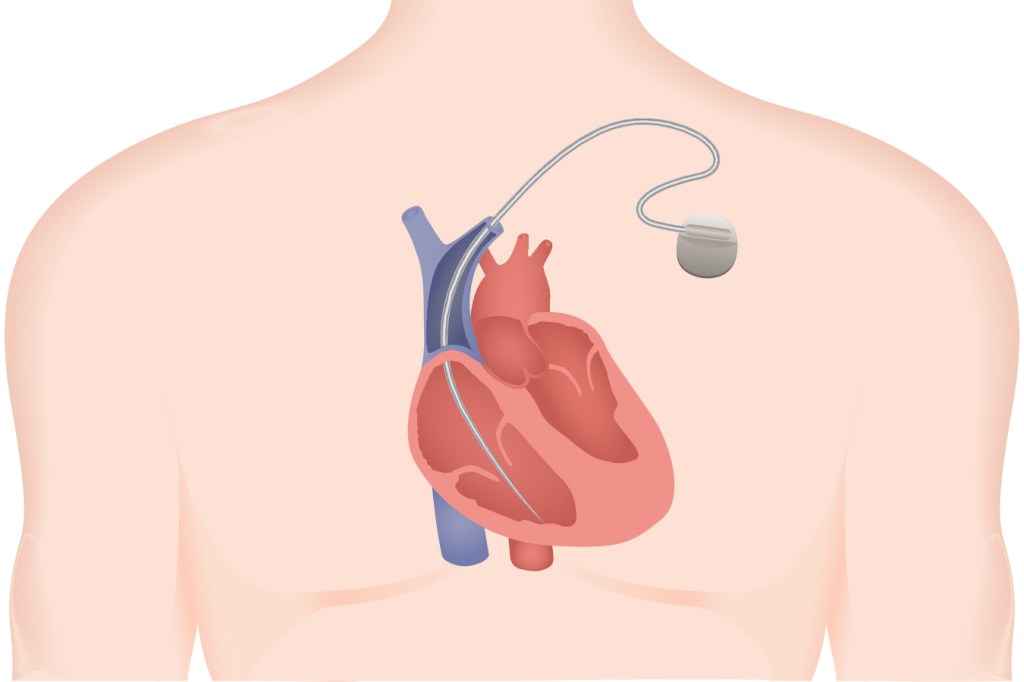

The device is a pair of wires tied to a defibrillator designed to shock the heart back into a normal rhythm. By the time it was recalled in late 2007, the Sprint Fidelis had been implanted in the heart tissue of 268,000 patients.

While doctors and patients can voluntarily report problems with the device, the FDA requires device makers to report to MAUDE the injuries they become aware of — unless they have an exemption.

Through March, Medtronic says, it logged more than 50,000 instances of harm or malfunction, with more than one problem reported for some of the 35,000 cases.

While a few reports in the MAUDE database refer to the existence of an exemption for the Sprint Fidelis, the FDA has said these “remedial action” reports are filed internally and available to the public through a Freedom of Information Act request, which can take nearly two years to process.

Medtronic, which supplied data on the exemption for this story, said that its Independent Physician Quality Panel has been reviewing data on the device since 2007 and that the information has been periodically reported to physicians. “Patient safety is our top priority,” spokesman Jeffrey Trauring said in an email.

Trauring said his company operates the “most comprehensive [defibrillator] lead surveillance program in the industry.” He also said Medtronic has updated information for doctors about the lead’s performance with the “most reliable data,” as compared with the FDA’s open MAUDE database and its “significant and well-established limitations.”

Kotz said via email that the FDA has “worked closely with Medtronic” to monitor the performance of the recalled leads and “ensure appropriate patient management recommendations are available to clinicians” in twice-yearly performance reports.

“[Medtronic provides] additional information on product performance and safety in a more comprehensive format than what we receive in summary reports,” Kotz said.

None of the Medtronic publications, though, offer details about the 50,000 malfunction and harm reports the company lodged with the FDA over 10 years. Those until-now-unacknowledged reports define the number of lead fractures or instances of inappropriate shocks.

The Medtronic reports tally less specific “advisory related events.” They also track more detailed malfunctions for a smaller number of devices either shipped back to the company or enrolled in a study.

Detective Work

A dozen years ago, before Sprint Fidelis was recalled, Hauser was a practicing cardiologist at the Minneapolis Heart Institute when two patients in one weekend arrived with fractured Sprint Fidelis leads. Hauser said he looked at the center’s files and found five similar cases.

Then he delved into MAUDE and found even more cases. He called Medtronic. He published a paper about what he had found, which he said “went viral.”

On Oct. 15, 2007, Medtronic issued a recall, saying the device gave some patients inappropriate shocks and was a “possible or likely” contributing factor in five patient deaths. The company later revised the death count to 13.

The thinnest defibrillator lead marketed to date, researchers said the Sprint Fidelis wires were prone to send faulty signals to the defibrillator, causing patient injuries.

In its 2007 letter to doctors, Medtronic advised against surgically removing the lead, citing rates of major complications, including death, ranging from 1% to 7%.

The recall was big news. Patients would testify to Congress or tell journalists about unexpected shocks that felt like a cannon to the chest or being kicked by a horse.

Then-House oversight committee chairman Henry Waxman fired off a letter to the FDA a week after the recall, in part asking about the company’s reporting of adverse events.

The agency acknowledged in a Dec. 13 response letter that Medtronic was reporting “the majority of adverse events” on their implantable defibrillators to the FDA “in aggregate electronically, via compact discs.”

Medtronic’s Trauring said at the time the company had an “alternative summary reporting” exemption for cases of lead infections or erosion, which meant the wires had moved out of position inside the body.

Six months later, on May 8, 2008, the FDA gave Medtronic a second exemption, allowing the company to report problems central to the recall outside of public scrutiny.

Trauring said in an email that under that second “remedial action” reporting exemption, Medtronic reported a total of 36,914 cases with 50,205 complications.

They include more than 22,000 instances of lead fracture and nearly 2,900 incidents of inappropriate shocks. Trauring said the company discontinued the summary reporting on Nov. 1, 2018, due to low volumes of issues.

Death cases were not filed with the reports granted exemptions. Since the 2007 recall, more than 2,300 reports of deaths in which the device was suspected to have played a role were filed with the FDA and are publicly available, records filed in MAUDE show. A 2009 report says one patient had 13 painful shocks and then bleeding during a surgery to remove his faulty lead. An attorney reported to the FDA that within months that patient died.

In 2012, a patient with a faulty device died after a major vessel was torn during a surgery to remove the lead. In 2015, a patient went to the emergency room after getting five shocks, was deemed to be in heart failure “exacerbation” and died in the hospital four days later, reports in MAUDE show.

Meanwhile, researchers trying to measure the harm resulting from the faulty device were reaching different conclusions. While Medtronic-backed studies were reporting a three-year lead survival rate of 95% to 97%, Hauser and his colleagues found a lower rate, 88%, according to a 2010 article in the Netherlands Heart Journal.

Dr. John Mandrola, a cardiologist at Baptist Medical Associates in Louisville, Ky., said the Sprint Fidelis was the “worst cardiac device problem” he has seen in 22 years of practice. He said some of his patients were traumatized by unexpected shocks and the repercussions went on for years. That the FDA did not publicly report ongoing harm “seems problematic to me,” he said. “What is the benefit to the public of an exemption?”

Dr. Frederic Resnic, cardiovascular medicine division chairman at Lahey Hospital & Medical Center in Burlington, Mass., and a Tufts University medical school professor, has testified to Congress about device safety. He said in an email that he commends the FDA for recent work to modernize safety surveillance for medical devices, but the “lack of communication and transparency” over the Sprint Fidelis exemption “challenges the FDA’s unique role as the primary, trusted, information source regarding medical device safety.”

Dr. Rita Redberg, a University of California-San Francisco cardiology professor and editor of JAMA Internal Medicine, said the FDA has acknowledged that device-related problems are woefully under-reported.

“Now the FDA is making it worse intentionally,” she said. “I can’t think of a justification for it, and I think it’s a dangerous practice.”

KHN data correspondent Sydney Lupkin contributed to this report.