J. Ronald Verrier

Age: 59

Occupation: Surgeon

Place of Work: St. Barnabas Hospital in the Bronx, New York

Date of Death: April 8, 2020

Dr. J. Ronald Verrier, a surgeon at St. Barnabas Hospital in the Bronx, spent the final weeks of his audacious, unfinished life tending to a torrent of patients inflicted with COVID-19. He died April 8 at Mount Sinai South Nassau Hospital in Oceanside, New York, at age 59, after falling ill from the novel coronavirus.

Verrier led the charge even as the financially strapped St. Barnabas Hospital struggled to find masks and gowns to protect its workers — many nurses continue to make cloth masks — and makeshift morgues in the parking lot held patients who had died.

“He did a good work,” said Jeannine Sherwood, a nurse manager at St. Barnabas Hospital who worked closely with Verrier.

“He can rest.”

Born in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, Verrier graduated from the Faculté de Médecine et de Pharmacie in 1986 and trained at Lincoln Medical Center in the Bronx. He worked at St. Barnabas for two decades, performing thousands of surgeries on critically ill patients and trauma victims, while overseeing the general surgery residency program.

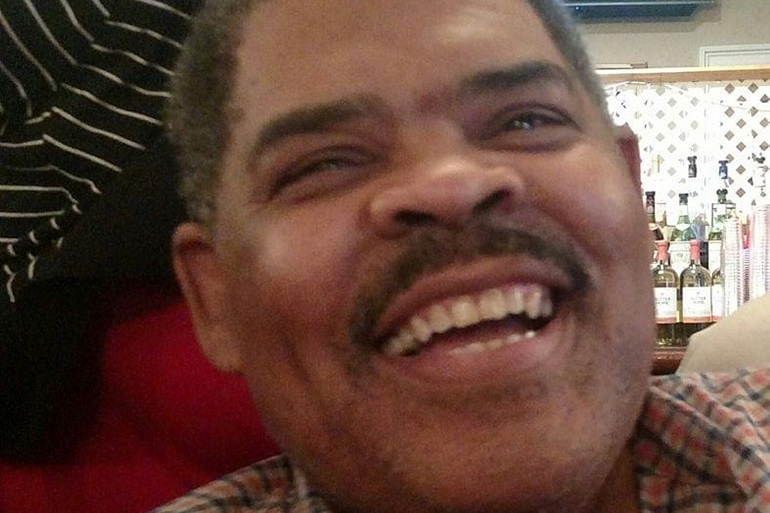

A towering presence with a wide, dimpled smile, Verrier watched his large flock closely — popping into patients’ rooms for impromptu birthday parties, pressing his medical school residents to sharpen their surgical skills and extinguishing doubt in bright, young minds.

“He kept pushing me forward,” said Dr. Christina Pardo, a cousin who became an obstetrician and gynecologist. “I would call him and say, ‘I swear I failed that test,’ and he would laugh. He was my confidence when I didn’t have it.”

“He was someone you’d love to see if you were having a bad day,” said Dr. Ridwan Shabsigh, chairman of the Department of Surgery at SBH Health System. “He would comfort your heart.”

The Verrier family stretches across continents — a boisterous crew of cousins who grew up as brothers and sisters, a pot of joumou, a spicy Haitian soup, always boiling somewhere.

Verrier, who spoke English, French and Creole, zipped around to a niece’s wedding in Belgium, a baptism in Florida, another wedding in Montreal. In February, he ferried medical supplies to Haiti, returning to St. Barnabas to fortify the hospital for the surge of coronavirus patients.

Verrier helped steer the hospital’s efforts to increase — by 500% — the number of critically ill patients it could care for, an effort he worked on until he became ill.

“He was at the hospital every day,” Shabsigh said. “This was a nonstop effort, day and night.”

Verrier discovered he was infected in early April. After developing symptoms, he worked from his Woodmere, New York, home.

Undaunted, he did not want to talk about being sick. “He has this personality that, ‘Everything is going to be OK,’” said Pardo.

Shabsigh spoke with him the day before his death.

“He understood the coronavirus, he understood the pandemic,” he said. “He still maintained a high morale and hope that he would recover.”

When his condition worsened suddenly, according to Pardo, Verrier was taken by ambulance to a nearby hospital where he died.

After a powerful earthquake struck Haiti in 2010, Verrier tended to victims, treating dozens of patients who required amputations at a Port-au-Prince hospital.

“Sometimes you use a little anesthesia and you cut the limb,” Verrier said soberly in a video recorded at the time. “Because you have to save a life.”

This story is part of “Lost on the Frontline,” an ongoing project by The Guardian and Kaiser Health News that aims to document the lives of health care workers in the U.S. who die from COVID-19, and to investigate why so many are victims of the disease. If you have a colleague or loved one we should include, please share their story.