After legal battles and lobbying efforts, tens of thousands of people with hepatitis C are gaining earlier access to expensive drugs that can cure this condition.

States that limited access to the medications out of concern over sky-high prices have begun to lift those restrictions — many, under the threat of legal action. And commercial insurers such as Anthem Inc. and United HealthCare are doing the same.

Massachusetts is the latest state to decide that anyone with hepatitis C covered by its Medicaid program will qualify for the newest generation of anti-viral drugs. Previously, managed care plans serving Medicaid members often limited the drugs, with a list price of up to $1,000 a pill or more, to people with advanced liver disease only.

The expansion follows a threatened lawsuit against drugmakers by Massachusetts’ attorney general, which induced companies to offer the state bigger rebates on the medications, making them more affordable.

Over the past few months, Florida, New York and Delaware have also expanded access in their Medicaid programs. And in April, a federal judge ruled that Washington state couldn’t withhold treatments from Medicaid members with hepatitis C who hadn’t yet developed serious medical complications.

“I think the writing is on the wall for restrictive policies, and plaintiffs are likely to prevail in these lawsuits,” said Nicholas Bagley, a professor of law at the University of Michigan.

“These aren’t me-too drugs with marginal benefits: they’re actual cures. While their cost is a huge fiscal problem, states aren’t permitted under the law to restrict access to medically necessary therapies on the grounds that they cost too much.”

Hard Decisions

The problem for states that are lifting restrictions: how to offset the expense of covering thousands of patients who may now come forward for hepatitis C treatment. “We want to give these medications to everybody who needs them, but with the prices they’re commanding, something has to give,” said Matt Salo, executive director of the National Association of Medicaid Directors. “We’ve run out of escape valves.”

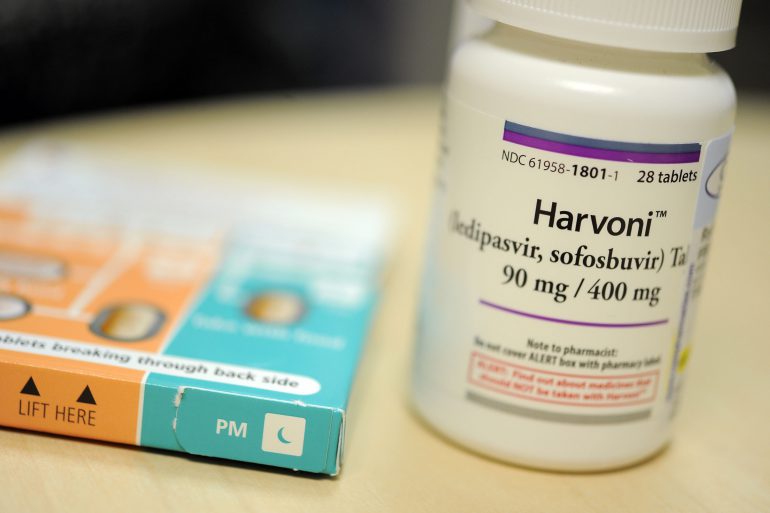

The drugs in question — Sovaldi and Harvoni from Gilead Sciences, Viekira Pak from AbbVie Inc., and Zepatier from Merck & Co., among others — eliminate the hepatitis C virus over 90 percent of the time, a cure rate almost double that of earlier therapies. The latest entrant in this market, Gilead Sciences’ Epclusa, received approval from the Food and Drug Administration last week.

But with a sticker price of $54,600 to $94,500 for an average 12-week course of treatment, dozens of states balked at the budgetary implications and provided the medication for only the sickest patients.

Private insurers followed suit in their group and individual plans, but many have been reversing those policies recently, also under the threat of lawsuits. Anthem Blue Cross and Blue Shield plans in 14 states quietly began authorizing treatment to people “in all stages of fibrosis” (liver scarring) in December, the company confirmed in an email. Previously, medication had been limited to hepatitis C patients with severe fibrosis or cirrhosis.

UnitedHealthcare enacted the same policy nationwide on Jan. 1, according to an email from the firm. After a March legal settlement with New York’s attorney general in New York, seven commercial insurers there are extending hepatitis C treatments to people who haven’t yet developed serious liver disease.

Meanwhile, in March, after Congress appropriated extra funds, the Department of Veterans Affairs said it would treat anyone in its health system with hepatitis C, regardless of the stage of illness — a move that could extend therapy to nearly 130,000 veterans.

Medicare embraced a similar policy after acknowledging that medical guidelines recommended that all hepatitis C patients receive care, with a few exceptions.

Easing Access To Therapy

Although up-front costs of covering more people with hepatitis C could be enormous, significant savings are possible longer-term, as transmission of infections is reduced and complications such as liver failure, cancer, and kidney disease are avoided.

“I’m so happy: having this chance to get healthy is amazing,” said Vickie Goldstein, 57, of Delray Beach, Florida, who’s had hepatitis C since 2003 and is now taking Viekira Pak. Her Medicaid managed care plan earlier had refused access on the grounds that she wasn’t sick enough.

Goldstein’s experience figured prominently in the legal case in Florida. The state’s Medicaid program settled after the National Health Law Program and local advocates presented a demand letter.

Settlement talks are also underway in Indiana, where the American Civil Liberties Union filed a class action lawsuit. And Pennsylvania’s Medicaid program is considering whether to adopt new standards after its Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee recommended in May that all patients with hepatitis C receive treatment. Connecticut adopted new policies expanding access to the medications last year.

Medical Necessity Is Key

Nationally, at least 3.5 million people are believed to have hepatitis C, although half of them don’t know it. Three-quarters are baby boomers who likely became infected from contaminated blood (the blood supply wasn’t tested for this virus until 1992), injection drug use, or sex. About 1 million are thought to be covered by Medicaid, a joint state-federal program for the poor.

By law, Medicaid and Medicare are required to cover medically necessary treatments; they can’t exclude an entire class of medications that are proven effective for cost considerations alone. Commercial insurers also typically agree to provide all medically necessary care.

There is widespread agreement in the medical community that new hepatitis C therapies meet this standard. Their benefits apply even to people who haven’t yet developed serious liver disease, according to guidelines from the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease and the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

“I’ve never encountered a colleague who’s questioned the wisdom of treating everyone,” said Dr. John Scott, director of the liver clinic at Seattle’s Harborview Medical Center and a member of the committee that drafted the guidelines.

Last November, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services issued a bulletin attempting to clarify the legal situation. A drug for a specific disease may be denied only if “the excluded drug does not have a significant, clinically meaningful therapeutic advantage in terms of safety, effectiveness, or clinical outcomes,” it wrote.

The price of medications should fall as new therapies come on the market, increasing competition, CMS noted. Gilead Sciences has said average discounts are about 46 percent off the sticker price, but discounts may be even greater, bringing the cost of drugs down to $30,000 or even lower, according to Kevin Costello, director of litigation at Harvard Law School’s Center for Health Law & Policy Innovation.

States are trying to use their bargaining power to force concessions. Massachusetts succeeded in doing so last week, when Gilead and Bristol-Myers Squibb agreed to provide deeper discounts, responding to the attorney general’s threat of a lawsuit. The extent of rebates was not disclosed. But lower prices for the medications will mean that more patients will have access, Attorney General Maura Healey said.

CMS Acting Administrator Andy Slavitt took the occasion to take issue with the high price of hepatitis C drugs and urge “manufacturers and pharmacy benefit managers to continue to find innovative ways to make them more affordable to state Medicaid programs and the beneficiaries they serve.”

Costello’s center was a key player in the lawsuits in Washington state and Delaware and plans to bring similar actions elsewhere. “A 50 state solution is what we’re looking for,” he said.

Having lost in court, Washington Medicaid officials are now trying to figure out how many patients may come forward and how much the state can expect to pay for hepatitis C drugs.

Anthony Slack, 63, is a former drug addict who’s disabled by degenerative arthritis and was diagnosed with hepatitis C in 1998. He is on a waiting list for treatment at the Harborview Hepatitis and Liver Clinic in Seattle.

“They said my liver wasn’t scarred enough and I wasn’t sick enough to get the medications,” Slack said in a phone interview. “I appealed it and still they turned me down. … I ain’t going to give up: This is my life we’re talking about.”

A priority will be providing therapy to people, like Slack, who have filed appeals, said Amy Blondin, a spokeswoman for the Washington State Healthcare Authority.

“The clinic said I should be hearing from them soon, and that made me feel real good,” Slack said. “I’m trying to keep hope alive.”