A low-profile commission that advises Congress on Medicare has renewed its call for lawmakers to reinvent from the ground up the way doctors, hospitals and other providers are paid.

The commission’s annual report, released today, repeated its 2008 recommendation, saying, “To increase value for beneficiaries and taxpayers, the Medicare program must overcome the limitations of its current payment systems.” Back in 2006, the report described “perverse payment” and “fragmented delivery systems.” Since then, little has changed, commission officials say.

“We definitely think that there’s a crisis and we need change,” said Mark Miller, the executive director of the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, called MedPAC. “The pressure has to be on,” he added, for hospitals, physicians, and other providers, whose “payment system rewards doing more,” regardless of quality or value.

Proposals to rejigger Medicare payments are decidedly less glamorous than debates over how to expand insurance coverage or regulate insurers. Still, with Congress and the administration focused on a health care overhaul, MedPAC’s recommendations may be finding a more receptive-than-usual audience. In recent weeks, President Barack Obama, as well as congressmen, business leaders and outside experts, have all indicated a new interest in MedPACs long-ignored suggestions.

At a speech to the American Medical Association today, Obama said MedPAC’s recommendations would have saved $200 billion. “These recommendations have now been incorporated into our broader reform agenda.”

MedPAC’s recommendations include “bundling” of services into a single payment to encourage doctors to skip excess tests. They also include high-performance bonuses for providers who improve quality and increase value.

Some of these ideas, such as bundling, are getting interest in Congress. But as MedPAC said in today’s report, the current fee-for-service system, which pays providers for each service or procedure performed, limits “the benefit of these tools.”

Changing payment systems “have got to be key” in any final bill approved by Congress, said Jack Lewin, chief executive officer of the American College of Cardiology, at a conference on payment policy Friday. However, Lewin remained cautious: “I’m not sure it will be a central theme in the reform bills. I believe it could slip back and become relatively modest.”

One way to ensure that it doesn’t, Obama and at least one senator say, is to give MedPAC the authority to implement its recommendations with less interference by Congress and outside interest groups that might oppose changes that put their revenues at risk.

Sen. Jay Rockefeller, D-W.Va., introduced legislation last month that would move the commission into the executive branch and allow it to determine pay rates and reimbursement policies with only a yes-or-no vote from Congress. Obama proposed making MedPAC’s recommendations on cost controls binding unless opposed by a joint resolution of Congress. He noted, in a letter to the senators, that the process was similar to one used by a commission to close military bases.

MedPAC was created by the 1997 Balanced Budget Act to provide advice to Congress on Medicare payments and rules for reimbursing physicians. The annual rate-setting process often incites the health care lobby and provokes a congressional fracas.

Those who support empowering the commission paint it as a way to insulate Medicare rate-setting decisions from the pressure from industry lobbyists – something Obama implicated in his letter. A subsequent New York Times editorial pointed out that the proposal would give the commission “enormous power to set Medicare payment rates.”

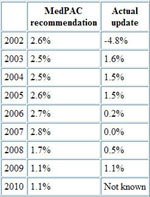

But that misses the point, some health analysts say. Congress hasn’t typically given providers better rates than MedPAC, which recommends increased payments in order to ensure access for Medicare patients. By contrast, members of Congress who in recent years have been worried about growing federal deficits have often given doctors and hospitals more modest raises than MedPAC suggested, or frozen the rates altogether.

In 2006, for instance, the commission suggested hiking payments for doctors by approximately 2.8 percent the following year–an adjustment based on market forces. Congress didn’t boost pay at all.

“If MedPAC is recommending a pretty substantial increase, often Congress can’t take that advice because they have other things to balance in the Medicare part of the budget,” says Joseph Antos, an economist at the American Enterprise Institute.

However, MedPAC has been much bolder than Congress in its suggestions to rejigger the current payment systems, which the panel says provides incentives to physicians to favor high-cost treatments and increase the volume of services they provide. Both behaviors contribute to ballooning costs.

To be sure, it is unclear whether the plan to empower MedPAC has legs in Congress. Rep. Michael Burgess, R-Texas, a physician, said, “I’m not a big fan of commissions, but what a commission is, is a way for congress to weasel out of tough decisions, to insulate us further from the people we represent.”

Also, a lobbyist for a physicians’ group said his members would oppose Rockefeller’s proposal partly because it would make lobbying more difficult. “We would lose our voice,” the lobbyist said. Reimbursement is a top issue for health professionals and hospitals, who gave nearly $120 million to political campaigns in the last election cycle, says the Center for Responsive Politics.

In the House, Ways and Means Committee Chairman Charles Rangel, D-N.Y., and Energy and Commerce Committee Chairman Henry Waxman, D-Calif., said in a press release today that they were developing a proposal to change the way physician reimbursements are calculated. They said the proposal would help make growth in primary care and preventive services sustainable, and to improve efficiency and coordination.

Meanwhile, in the Senate, Finance Committee Chairman Max Baucus, D-Mont., and Charles Grassley, R-Iowa, have proposed modest payment reforms, such as bundling reimbursements for certain treatments into a flat rate. In April, Baucus said, “We need to move away from paying for more care, and move towards paying for better care.”

Groups ranging from the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation to the Brain Injury Association of America have responded by saying such steps could delay or undervalue patient care.

But not all providers resist the payment changes. Last week, a group of health care chief executive officers many representing large, integrated care systems that have already improved efficiency and quality denounced fee-for-service payments. Patricia Gabow, CEO of Denver Health, a Colorado-based health and hospital system, said, “We need a payment model that provides the appropriate incentives.”

And Miller, MedPAC’s executive director, said that reimbursements should support providers that are already achieving good outcomes. “How about setting up a payment system that rewards them?”