Delayed by state lawmakers, Michigan did not expand Medicaid until the day after the federal online insurance exchange closed March 31 – a move advocates feared would undermine signups.

Turns out, enrollment is exceeding expectations, which has pleased officials who seek to make the state among the first in the nation to add a heavy dose of “personal responsibility” to the federal-state entitlement program.

This spring, the Wolverine state became the second after Iowa to offer lower premiums and cost sharing to recipients who agree to do a health risk assessment with their doctor every year and to commit to improve their health by taking steps such as quitting smoking or losing weight.

“There is a heavy consumer engagement piece in this, both in terms of finances and skin in the game, but also in terms of healthy behaviors and really trying to find ways in which we can make the population of Michigan healthier,” Michigan Medicaid Director Stephen Fitton said in a briefing in Washington earlier this month. “We have a high obesity rate in Michigan. We don’t do very well on some broad [health] measures and we are really looking for ways to move the needle there.”

The hope is that giving people a financial incentive to change their behaviors will improve their health and control Medicaid spending.

Other states, such as Pennsylvania, are also seeking to tie Medicaid coverage to personal responsibility by seeking federal approval for a plan that would prod unemployed people to search for jobs and get annual wellness exams in exchange for lower premiums.

In an effort to give Medicaid recipients more “skin in the game,” as proponents call it, most newly eligible Michigan recipients will face copays — typically from $1 to $3 for most outpatient health services. Those with incomes between 100 percent ($11,670) and 138 percent ($16,105) of the federal poverty level will also pay a premium of 2 percent of their income.

While many states impose similar cost-sharing, Michigan will be the first to ask enrollees to make those payments — either co-pays or premiums or both — through a health savings account. Indiana Gov. Mike Pence, a Republican, has also recently proposed health savings accounts as part of his Medicaid expansion plan.

Both the state of Michigan and individuals and potentially, their employers, will be asked to deposit money into those accounts based on enrollees’ copays in the prior six months. If funds are left at the end of the year, they will be rolled over. If a beneficiary becomes ineligible for Medicaid, the balance will be put into a voucher they can use to buy private insurance.

Joan Alker, executive director of the Georgetown University Center for Children and Families, credits the state for using the “carrot approach over the stick approach,” but said there’s little evidence such incentives improve enrollees’ health.

“We know from the employer world, this is very hard to do,” she said.

She said the complexity will also make it harder for the state to implement the plan. “The legislation adds a lot of red tape,” she said.

Enrollees with incomes above the poverty level who fill out health assessment forms and commit to healthful practices can reduce their premiums by half. Individuals with a $12,000 income, for instance, could cut their annual premium of $240 to $120.

Enrollees with incomes below the poverty level won’t pay a premium though they are eligible for a $50 gift card if they complete their assessment form and agree to improve their health.

They don’t have to meet specific health goals to qualify for lower cost sharing or the $50 gift card beyond filling out the assessment with their doctor once a year and attesting that they will do such things as eating better, exercising more or getting a flu shot.

The state is still trying to decide what to do if a recipient fails to contribute to the savings account. Losing Medicaid coverage is not an option, said Michigan Medicaid spokeswoman Angela Minicuci. The state is considering collecting unpaid contributions through a lien on tax refunds.

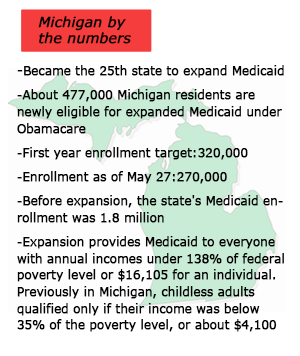

Michigan did not expand Medicaid until April because the legislature did not approve the move until last September and Republican opponents included a provision delaying the implementation until at least 90 days after the lawmakers adjourned their 2013 session. Michigan is the 25th state and one of eight led by Republican governors to expand the program. Gov. Rick Snyder also waited to make sure the state’s online enrollment was working to avoid a repeat of the botched federal exchange rollout.

Nonetheless, more than 270,000 low-income Michigan residents have signed up for Medicaid since April 1 — over half the estimated 477,000 eligible for the program. The signup pace has exceeded that of most of the 25 states that expanded Medicaid in January, which benefited from the publicity surrounding the open enrollment period for private plans. Unlike buying private coverage, people can sign up for Medicaid any time.

“I was absolutely worried about the timing,” said Conrad Mallett Jr., chief administrative officer for Detroit Medical Center, a large safety net hospital. He credits efforts by groups such as the Salvation Army to boost enrollment. “In 99 percent of the cases, poor people are just poor, not stupid — they know what this opportunity means in their lives.”

Nearly all of those newly eligible for Medicaid will get their coverage through a private Medicaid managed care plan. Health plan officials say the risk assessment will help them identify members who need help quitting smoking or, say, managing their diabetes.

“We take this as an opportunity to engage with members,” said Patricia Graham, director of operations for Detroit-based Meridian Health Plan. Her plan is also paying $25 to doctors as incentives to get them to help their patients fill out the health risk assessment and set some healthy behavior goals.

The state’s safety-net hospitals that treat many poor and uninsured patients are among the major beneficiaries of the strong Medicaid enrollment. “This will have a significant effect on Henry Ford Health System because every year we see our uncompensated care rising,” said Sharifa Alcendor, the hospital’s director of patient care management.

Alcendor, though, is concerned that hospitals and other providers will get stuck with extra costs if enrollees don’t pay into the health savings accounts.

Michigan health officials said their enrollment efforts gained from the publicity surrounding the Obamacare marketplace enrollment so there was still huge demand when Medicaid signups began in April. They also were able to switch 60,000 adults into Medicaid automatically on April 1 who had more limited coverage in a state basic health insurance program. Unlike a number of states such as California, which have a large backlog of people waiting to get insurance cards, Michigan officials say new enrollees have received their Medicaid cards within weeks — with coverage retroactive to first day of the month they signed up.

“We’ve been pleasantly surprised that we could enroll this amount of people in this short period of time,” said Phillip Bergquist, director of health center operations with the Michigan Primary Care Association.

Like most northern states, Michigan officials benefitted from a culture where residents are used to having insurance, said Josh Fangmeier, policy analyst at the University of Michigan’s Center for Healthcare Research & Transformation. Despite the state’s higher than average unemployment rate, its 13 percent uninsured rate in 2012 was below the nation’s 15.4 percent average.