WAYNESVILLE, N.C. — In the mountains of Western North Carolina, health insurance navigator Julia Buckner spends hours driving around what she calls “God’s Country” — miles and miles of mountains, rivers and winding roads. Her job – and her passion – is to help the rural residents of some of the poorest counties in North Carolina sign up for coverage through the Affordable Care Act.

But for nine out of ten of the people she talks with, she says, it seems as if there’s nothing she can do. They’re too poor to qualify for affordable health insurance in North Carolina, because they’re in what’s called “the coverage gap:” They don’t earn enough to qualify for a subsidy under the health law, and they can’t get Medicaid because North Carolina is one of the 23 states that decided not to expand the program under the health law. The expansion covers childless, low-income adults who previously didn’t qualify for Medicaid.

“I take someone who’s working poor, I ask them to come see me, and then I find out that not only are they poor, but they’re too poor for me to help. It’s almost as if I wished I hadn’t seen them,” says Buckner, who grew up in the area.

So now, the name of the game is the workaround – inventive ways that low-income consumers can earn enough to reach the poverty line ($11,500 for a single person) in order to qualify for a a subsidy. Sometimes, Buckner says, people haven’t thought of all the various things they can count as income, like a woman she spoke with who cleans houses for a living.

“We went through a bunch of questions, like what else could you consider income? And there’s this light that goes off. ‘Oh! Can I use the ginseng?’ And I said ‘Sure,'” she explains.

The woman can earn money selling wild ginseng from her yard, plus some extra money from a few new cleaning clients. That additional income pushes her over the poverty line. She was able to sign up for coverage on the exchange with a hefty subsidy.

Other people may be able to pick up a extra hours at work or count on extra money from odd jobs — taking care of an aging neighbor or babysitting, for example.

“Folks are trying to use every source of income, whether it’s selling tomatoes from their garden, or perhaps they’ve never actually sold the hay off of their field, they’ve just always let their nephew cut it for free,” explains Buckner.

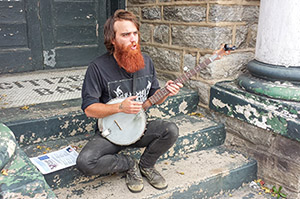

Or they might be able to get coverage under other provisions of the law. About 40 minutes away from Graham County, the local courthouse in Swain County lets Buckner set up shop in their small claims court when it’s not in session. Wandering around town, she spots a young man with a thick red beard and a flannel shirt, playing banjo in front of the bank.

She waits for a break in his playing and approaches. “Do you have health insurance?” she asks. “I do not,” replies John Martin, who adds that he used to have coverage through his mom’s plan but lost it when he turned 21. Now he works for the railroad, but during the off-season he’s unemployed. And he earns less than $11,500, which is 100 percent of the federal poverty level for a single adult.

But it turns out that he’s only 24. Bingo. The law allows people under 26 to stay on a parent’s plan. And it worked. Martin was able to get coverage through his mom and is now insured.

Even for those a little older, there might still be options.

At a church in nearby Franklin, Chuck Cantley stopped by a presentation about the health law after receiving a letter from Blue Cross Blue Shield explaining that the plan he was getting for $240 per month would soon cost him $1,100.

“Well, I can’t do that,” said Cantley. “I’ve got to find another option. Either that or I won’t have insurance.”

Cantley, 62, is retired but was waiting to collect Social Security until he was 66, hoping to get a higher monthly rate. But he needs health coverage now. So he applied for Social Security early, which pushed him and his wife up to the poverty level. He qualified for a big subsidy and signed up for coverage on the health insurance exchange.

Success stories like Cantley and Martin are the minority, but they give Buckner hope.

“The folks that have been able to sign up, they are ecstatic,” she says. “And as long as we keep hearing success stories, that energy and excitement are going to grow.”