Suppose you have prostate cancer, and you want to know what to do. Surgery, your doctor warns, can be physically debilitating, but is generally effective and low risk. Radiation is not as taxing, but its effectiveness is uncertain. Or you could just wait and see, the doctor says. Many people live for years with prostate cancer and die of other causes. It’s up to you.

The same is true for parents wondering if they should use drugs to treat their son’s attention deficit hyperactivity disorder or a woman weighing whether to have a lumpectomy or mastectomy to treat DCIS, an early breast cancer. They, too, are often told that it’s their call.

In an era when many patients are eager to look up their latest diagnosis on the Internet and talk to three specialists before committing to a medical procedure, this is not an unusual conversation. Patients want to be partners with their doctors in determining the course of their care. But for many conditions, there are no good guideposts.

The authors of the 2010 federal health law wanted to help. The law established an independent nonprofit organization called the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). Its mission is to compare treatments to determine which options make the most sense for particular people.

Although European countries have long used such comparisons to help set care standards, “comparative effectiveness research” is a relatively new concept in the United States. In fact, the U.S. health system, which largely follows a model that pays doctors and hospitals for any service provided, generally has not embraced comparative effective research.

PCORI faces several major challenges:

— Identifying research priorities for patients based on the study of hundreds of medical conditions and the questions they pose.

— Avoiding political criticism from opponents who argue that PCORI will ration care, some even calling it a “death panel.”

— Maintaining support from medical device makers and drug companies that are concerned the institute will be simply a cost control mechanism.

— Devising strategies for conducting studies to provide meaningful results.

“Making research relevant is a very fundamental issue,” said Dr. Harlan Krumholz, a Yale University cardiologist and a member of the PCORI board. “We want to design and carry out studies that take into account the heterogeneity of patient populations.” It is key, he said, “to connect with the patients, to provide new knowledge for individual patients.”

Options For Conducting Research

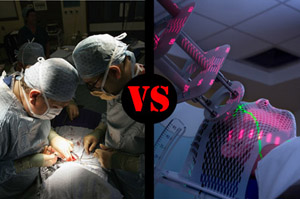

There are three basic ways to do the research, and each has both strengths and weaknesses.

- Systematic reviews examine all the research that has been done on a particular question. Although this can produce generally unbiased results, it does not offer new evidence.

- Observational research compares two treatments for the same disease or condition by examining medical records. Problems arise, however, because of what’s missing. If a doctor decides that a patient cannot have prostate surgery because he is too weak from other illnesses, he recommends radiation, but may not write down his reasons for the decision. If only robust patients get surgery, the study will be biased against radiation.

- Randomized trials are the gold standard for research. A researcher sets up a study with the stated purpose of comparing two or more treatments. The drawbacks of randomized studies are that they are expensive, take a long time and may be too specific.

“The heart of the matter,” Helfand said, is to “design and carry out studies that individualize the results. Often a question isn’t answered by just a randomized study or observational research. We have to make the research more applicable.”

–Guy Gugliotta

The institute has not fully outlined its plans, but it is reviewing past comparative effectiveness research. By the end of the year it expects to make a number of grants to identify what they need to find out from patients, for example, should they use social media to ask people what kind of information they want to have before making decisions.

Arthur Levin, director of the Center for Medical Consumers, an advocacy group, noted that in addition to enhancing the quality of the research, reaching out to patients can help the institute shed concerns about rationing that were raised by opponents in the health care debate: “You have to build public support,” Levin said, “because it’s so easy for the opposition to latch on to this.”

The law attempted to wall off PCORI from much of that fury. Although established by the federal law, the institute operates as an independent nonprofit using a trust fund that will provide an estimated $860 million between 2010 and 2014, and about $500 million per year from 2015 to 2019.

By law, the institute is forbidden to consider the cost of different treatments either in setting its research agenda or in drawing its conclusions. That provision has helped tamp down concerns of medical device manufacturers and drug companies. They want PCORI to “focus on clinical research and not cost effectiveness,” said David Nexon, senior executive vice president for AdvaMed, the medical technology manufacturers’ trade organization.

“For us, the biggest thing is that all stakeholders participate, that the process is transparent and that there are ample opportunities for comment along the way,” Nexon said. “The final version (of the legislation) does that. Everybody has a voice.”

Also, 19 of the institute’s 21 board members were chosen by the nonpartisan Government Accountability Office, and the directors of the National Institutes of Health and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality chose the other two. The board chairman is Eugene Washington, vice chancellor for health services at UCLA and dean of the medical school there.

If done well, PCORI’s research could empower patients to make informed choices about treatments and help them steer clear of unnecessary and perhaps expensive options, something that both sides of the political spectrum should endorse, said Dr. Harold C. Sox, former editor of Annals of Internal Medicine and emeritus professor at Dartmouth Medical School. “The basic mission is to insure that patients are well-informed and can have informed conversations with doctors,” he noted. “Shared decision-making is not a blue-red issue.”

In 2009, Sox led an Institute of Medicine (IOM) study on setting priorities in comparative effectiveness research. The study lasted only four months, but it provides a glimpse of what PCORI’s agenda might eventually look like. Both Washington and Dr. Joe V. Selby, the institute’s executive director, were part of the IOM’s 23-member study panel.

Besides participation from doctors, researchers, insurance companies, industry and consumer advocates, the IOM committee also received information and queries from patients both on the Internet and at public meetings. As part of its report, the IOM produced a list of 100 research priorities.

Some of these simply asked for comparisons of different medical treatments. What was the best way to deal with prostate cancer? Was surgery, catheter ablation or medication recommended in treating atrial fibrillation?

Others were almost entirely behavioral: compare school-based interventions, like vending machines, meal programs and exercise at various levels of intensity, in treating childhood obesity. And others were clinical: how effective are interventions such as prenatal care, nutritional counseling, smoking cessation and substance abuse treatment in reducing infant mortality?

Dr. Mark Helfand, a staff physician at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Portland, Ore.and a member of the IOM committee, said that unlike the IOM panel, PCORI is “an ongoing” organization that will need “broader and more intense ways of involving the public.”

“There is a real advantage in going back and looking at a longer term frame,” Helfand said. “As people participate in this process they become involved and knowledgeable in different ways.”