“I’ll deal with it tomorrow. The perpetual tomorrow.”

That’s what one person told a pollster, encapsulating how Americans avoid planning ahead for serious illness and death.

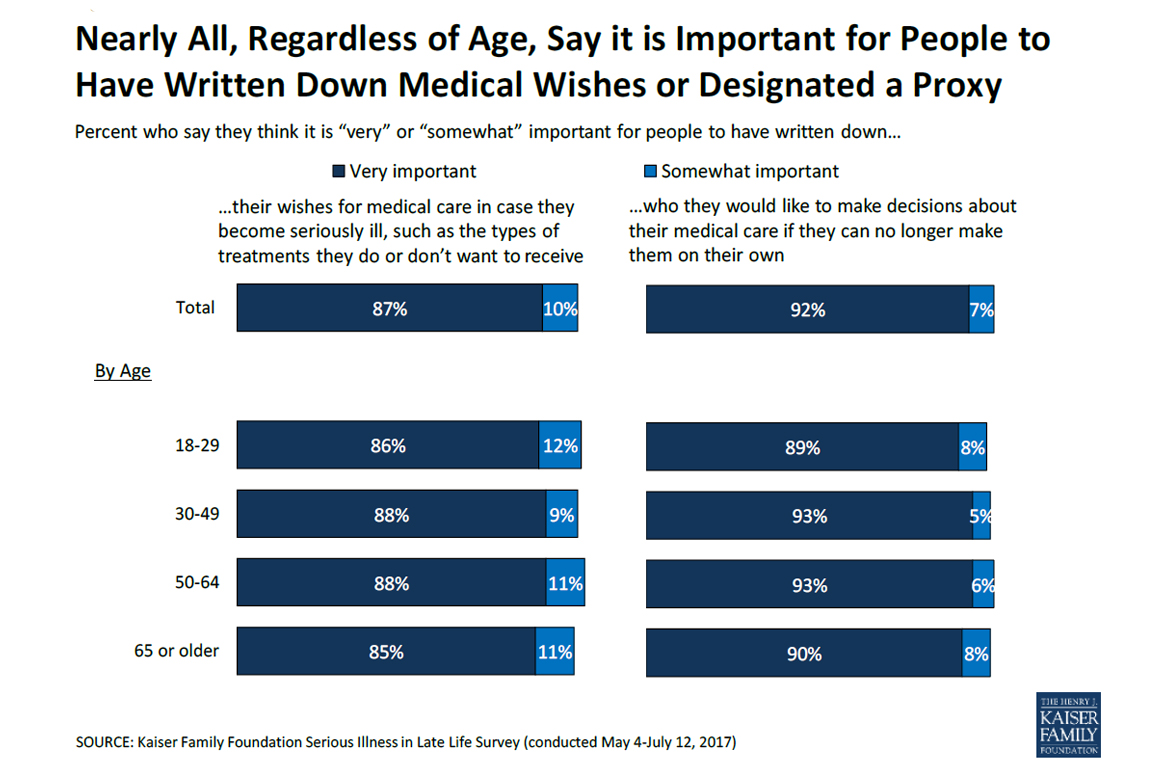

While the vast majority of Americans say it’s important to write down their medical wishes in case they become seriously ill, only a third have done so, according to the poll, released Thursday by the Kaiser Family Foundation. (Kaiser Health News is an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation.)

When adults with serious illness don’t write down their wishes, family members are much less likely to know exactly what their loved one would want, and the adults themselves are less likely to feel their wishes are closely followed, the poll found.

The poll surveyed a representative sample of 2,040 American adults by phone, including 998 with direct experience of serious illness in the family.

Americans 65 and older are more prepared than younger Americans but, still, only 58 percent in that age group have a written document outlining their medical wishes in case of serious illness, and 67 percent have documented who they want to make medical decisions on their behalf if they become incapacitated, the poll found.

The top reason people gave for avoiding these tasks is that “there are too many other things to worry about right now.”

The poll identifies differences across racial and ethnic groups:

Black adults 65 and older were far less likely than white and Hispanic counterparts to have written down their medical wishes.

Black and Hispanic adults were more likely than whites to cite “don’t want to think about sickness and death” as a major reason they didn’t document their wishes.

The poll also highlights challenges faced by seriously ill adults and their families. A seriously ill adult is defined as someone 65 or older who has a chronic condition, such as diabetes, asthma or heart disease, and also has functional limitations, such as difficulty eating, dressing or using the toilet. The findings include:

- About half of adults with serious illness had trouble understanding instructions for medications and medical care in the previous year.

- One in five family caregivers said no one can give them a break if they need it.

- About a third of family caregivers said they did not receive any training on how to move their loved one safely, recognize signs of pain or distress, or administer medications.

“The one thing I would say, for my family members, I was able to show them how to wash hair, how to change the bed with the person in it, those things,” one caregiver told pollsters. “But it would have been so helpful if the hospital, community center, anybody, had offered some basic classes.”

KHN’s coverage of end-of-life and serious illness issues is supported by The Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.