Irene Mooney survived four heart attacks and still copes with high cholesterol, persistent indigestion and heart problems. Recently, she developed some dangerous new symptoms – suspicious bruising all over her body and severe fatigue. “I could barely put one foot in front of the other,” she says. A pharmacist discovered the culprit: Some of the very medications Mooney was taking to manage her medical conditions.

The pharmacist met with Mooney, examined her 13 medications and then contacted her doctor, who cut the dosage of one drug and replaced another, reducing her risk of uncontrollable bleeding. Mooney, 82, one of the devoted card players at her seniors’ complex, soon noticed the change. “I’ve been so much better,” she says.

The help Mooney got – called “medication therapy management” – was provided by Senior PharmAssist, a Durham, N.C., non-profit group that makes sure seniors use the right prescription drugs and take them correctly to prevent harmful side effects or drug interactions.

Now, medication management is coming to nearly 7 million seniors and disabled Americans enrolled in Medicare drug plans. Under new, tougher Medicare rules that took effect in January, private insurers that offer drug coverage must automatically enroll members who have at least $3,000 in total annual drug costs, take several drugs and have chronic health conditions such as diabetes, hypertension or heart disease.

Insurance company representatives – in most cases, pharmacists – are required to ask these members about their medications and side effects. They must report any problems to patients’ doctors, along with recommended changes such as lowering the dose or replacing or eliminating a drug. Patients can drop out of medication management at any time.

The goal is to keep seniors healthy by detecting medication-related problems. That would be welcomed by most doctors, says Peter DeGolia, director of geriatric medicine at University Hospitals Case Medical Center in Cleveland.

Yet he’s concerned that health plans might pressure members to take cheaper or fewer drugs. If that happens, he says, doctors won’t comply. “Sometimes it’s beneficial for the insurance plans, but not the patients,” he says.

R. Sean Morrison, a professor of geriatrics and palliative medicine at Mt. Sinai School of Medicine in New York City, warns that medication management could backfire because pharmacists working for the insurers don’t know the patients’ medical history. “These are often not simple and straightforward decisions,” he says.

Strengthening The Rules

Insurers say they can play an important role in the doctor-patient relationship.

Catherine Misquitta, pharmacy director for Health Net, which provides drug coverage to more than 687,000 seniors, cites “numerous cases” in which neither the member nor the physician realized – until Health Net told them – that the patient had two very similar drugs for the same condition prescribed by different physicians, usually a primary care doctor and a specialist.

Ed Pezalla, the chief of Aetna’s pharmacy division, which has more than 586,000 drug plan members, says even when a pharmacist suggests a less costly drug, “the final decision always rests with the patient and the prescribing physician.”

Nearly 28 million older and disabled people get Medicare-subsidized drug coverage from insurance companies. Almost a quarter of them will be eligible for medication management under the new rules – about twice as many as last year, Medicare spokesman Peter Ashkenaz says. When Medicare drug coverage took effect in 2006, Congress required health plans to provide medication management, but the rules were so vague that an insurer could comply simply by sending a brochure to someone with diabetes.

Under the tougher rules, that won’t be enough. The service must include an annual medication review and quarterly reassessments. Discussions must be in person, over the phone or via the Internet, and seniors must get a written summary.

William Fleming, Humana’s vice president of pharmacy and clinical integration, says a patient who takes the correct drugs – whether they’re brand-name or cheap generic versions – may stay healthier and file fewer medical claims.

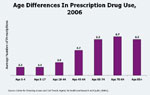

People over 65 take twice as many medications as younger adults, an average of six to seven drugs for multiple chronic health problems, according to a study by the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Seniors often get prescriptions from multiple doctors and fill them at different pharmacies. Aging bodies process medications less efficiently, so normal doses can build to dangerous levels. Seniors who can’t afford their medications may skip doses or cut pills in half.

Any one of these situations could cause serious problems, says pharmacist Gina Upchurch, founder of Senior Pharm8Assist.

Meetings Not Required

Upchurch worries that Medicare’s medication management won’t detect such problems because the new rules don’t mandate face-to-face meetings with patients.

“I can’t teach you to use an inhaler without seeing you,” Upchurch says. “I can’t see if you are drawing up your insulin correctly over the phone.”

Ashkenaz says officials were reluctant to impose such a requirement because some older people may have trouble getting to those meetings. The agency will consider changes as they evaluate reports from insurers.

Geneva Boykin, 79, went to Senior PharmAssist last year after complaining of stomach pain. A pharmacist reviewed her 14 medications and contacted Boykin’s doctor, who stopped one drug and reduced the dosage of another. Six months later, in January, Boykin returned with good news. “I don’t have the burning in my stomach,” she said.