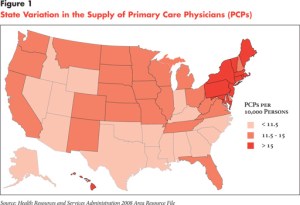

States in the South and Mountain West, which traditionally have the lowest rates of primary care physicians, could struggle to provide medical services to the surge of new patients expected to enroll in Medicaid under the health overhaul and federal incentives may not provide much help, according to a report issued today by a Washington health research group.

The study, by the Center for Studying Health System Change, noted that many of the states with low numbers of primary care doctors per capita are also expecting some of the highest percentage increases in Medicaid enrollment. The study’s author – Peter Cunningham – estimated that Medicaid programs could grow by as much as 38 percent in states with low rates of primary care physicians, while only about 15 percent in those states that have high rates of the doctors-those in the Northeast and the Mid-Atlantic regions.

“Things are probably not going to be pretty in those states that have a hard time” recruiting primary care doctors, said Alwyn Cassil, the center’s director of public affairs.

The new federal health law will expand Medicaid eligibility starting in 2014 to those making up to 133 percent of the federal poverty level, or about $14,400 for an individual and just under $30,000 for a family of four. About 16 million people are expected to join the joint federal-state health program by 2019.

Many physicians currently do not accept Medicaid patients or limit the number they will see, saying the reimbursement rates are too low. That has raised concerns about whether the new enrollees will be able to find doctors.

The study analyzed responses from 4,700 physicians in general internal medicine, family practice and general pediatrics and found that physicians’ willingness to take on new Medicaid patients, who often face greater barriers to access, didn’t vary geographically.

The study also examined the potential impact of a boost in Medicaid reimbursement for doctors that was included in the health law. It found that the bump, which would put payment for certain primary care services on par with Medicare levels in 2013 and 2014, may have a more limited impact than expected and would also vary according to geography.

“If you thought the increased Medicaid reimbursement was going to get a lot more docs to jump in and be willing to take on new Medicaid patients, it’s not going to work that way,” Cassil said.

In general, states with low rates of primary care physicians — primarily in the South and West — tend to provide more generous Medicaid reimbursement to attract doctors to the program. On average, Medicaid reimbursement rates in those states are 81.6 percent of the reimbursement rates for Medicare, compared to 54.8 percent in the high primary care doctor states. That means the new Medicaid reimbursement bump will likely have less of an impact in those areas than in states with more primary care docs.

But the situation is complicated in those low-doctor states. They traditionally have more restrictive Medicaid enrollment. That means that when the new health law is implemented, they will have a higher percentage of residents suddenly coming into the Medicaid program, which makes the demand for doctors serving enrollees even greater.

Dr. Lori Heim, a family physician in North Carolina and a member of the board of directors of the American Academy of Family Physicians, said the report underscored the need to address the primary care shortage. “If you’re going to address the shortage areas, we have to look at a payment reform as well as how we deliver care,” Heim said.

The supply of specialists also poses a challenge as more states push Medicaid patients to join Medicaid managed care plans, which often lack enough specialists.