Before Luke Whitbeck began taking a $300,000-a-year drug, the 2-year-old’s health was inexplicably failing.

A pale boy with enormous eyes, Luke frequently ran high fevers, tired easily and was skinny all over, except his belly stuck out like a bowling ball.

“What does your medicine do for you?” Luke’s mother, Meg, asked after his weekly drug treatment recently.

“Be so strong!” Luke said, wrapping his chubby fist around an afternoon cheese stick.

Luke now spends days playing with his big brother, thanks to what he calls his “superhero” medicine, a drug called Cerezyme, which has saved his life.

For the Whitbecks, finding a way to pay for the drug has been a nerve-wracking struggle. Their family business and its insurer cough up hundreds of thousands of dollars per year, spreading the cost across the people it insures.

Cerezyme is an “orphan drug” which means it was created to treat a rare disease, one that affects fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S. The orphan drug program overseen by the Food and Drug Administration is loaded with government incentives and has helped hundreds of thousands of patients like Luke feel better or even stay alive.

But the 34-year-old program has opened the door to almost unlimited price tags and created incentives among drugmakers to cash in, and to cash in repeatedly, a Kaiser Health News investigation shows. The explosion has burdened insurers as well as government programs like Medicare and Medicaid with drugs that cost up to $840,000 a year that they have almost no choice but to pay for.

The Orphan Drug Act has clearly spurred the creation of rare disease drugs. And more are needed: The National Institutes of Health estimates that one of every 10 Americans suffers from a rare disease. All told, there are about 7,000 of them.

But the costs are adding up quickly.

Annual sales from orphan drugs are expected to grow 12 percent a year through 2020 — a pace that general drugmakers could “only dream about,” market watcher EvaluatePharma said in its most recent orphan drug report. In 2014, the average annual price tag for orphan drugs was $111,820 versus $23,331 for mainstream drugs.

What’s more, the number of orphan drugs is growing and their total portion of prescription drug spending is growing, according to EvaluatePharma. Orphan drug sales worldwide are expected to account for just over 20 percent of all drug sales, excluding generics, by 2020. Europe and Japan have strong orphan drug programs as well.

At Aetna, orphan drugs are now the fastest-growing part of the giant insurer’s spending on drugs and are driving up insurance premiums, said Dr. Ed Pezalla, Aetna’s former national medical director for pharmacy policy and strategy.

For many drugmakers, orphan drugs look so profitable that they’re drawing attention from mass-market drugs.

“Companies [are going] after the rare diseases … and a larger set of patients with other diseases [are] left behind,” said Alan Carr, a research analyst for Needham & Co.

High prices are a reflection of the high cost of developing new drugs, said Anne Pritchett, vice president for policy and research at the industry lobbying firm Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America.

“You may have a company that focuses on a rare disease area for 20, 30, years and never turns a profit [but] they keep at it,” Pritchett said.

Others dispute that calculation. In a December report to Congress, the Department of Health and Human Services said orphan drugs cost about $1 billion to develop compared with $2.6 billion for mass market drugs.

Bernard Munos, a former Eli Lilly executive now at the nonprofit Milken Institute, said orphan drugs cost $50 million to $200 million to develop at a small company. And regardless of the development costs, he said drugmakers will charge whatever they want “because they can get away with it.”

The creators of the orphan drug program, say the price spiral — and loopholes in the approval process — have undermined the spirit of a well-intentioned law.

“What was intended for a good purpose can be used for a purpose that’s harmful to patients who can’t afford drugs,” said former U.S. Rep. Henry Waxman, D-Calif., a primary sponsor of the 1983 Orphan Drug Act. “And it makes the whole cost of all of these pharmaceuticals much more expensive for everybody.”

‘That’s Not Normal’

One winter day in early 2016, Meg Whitbeck stood in her Connecticut home holding a baby onesie.

Meg’s days were filled with Luke spiking high fevers, rushing to the doctor’s office and watching her toddler struggle to keep food down. Just before slipping the onesie over Luke’s head, she paused.

It was a 12-month onesie; Luke was 18 months old.

“That’s not normal. Babies fly through clothes the first year-and-a-half of life,” Whitbeck said. As Meg lifted another onesie from Luke’s dresser, she took a deep breath as she realized: It was full of 9- and 12-month clothes.

Within weeks, Luke would be laying in a hospital bed at Maria Fareri Children’s Hospital in Valhalla, N.Y., If handed a toy, he would hold it but lacked enough energy to play. Luke was diagnosed with Gaucher disease — a genetic condition that affects only about 6,000 people in the U.S.

Luke’s body lacked the glucocerebrosidase enzyme, and every cell in his tiny frame was becoming compromised. Luke’s liver and spleen were swollen and without treatment his bones would eventually become fragile. Brain damage could follow. Some babies die before the age of two, if they aren’t treated. Patients can live decades with enzyme replacement therapy.

Dr. David Kronn, who heads the medical genetics unit at Maria Fareri, said Luke’s condition was “quite severe” and he needed help fast.

Luke immediately began treatment but the family said they spent months uncertain whether their health insurer Oxford Health Plans, which is owned by UnitedHealthcare, would cover the drug. The drug is made by Sanofi Genzyme and costs $6,356.69 for each treatment, the Whitbecks’ paperwork shows.

“At the time, there was a lot going on physically with Luke,” Meg Whitbeck recalled. In the first two months after his diagnosis, the family would receive bills and “we were just putting it all in a pile.”

In late April, the Whitbecks received a letter from the insurer asking for additional medical information to process the payments for Luke’s medicine. It was the first time, Meg said that she became scared about how the drug would be paid for. She recalled wondering: “How can something that’s going to keep my baby alive not be covered by insurance?”

UnitedHealthcare spokeswoman Tracey Lempner said her company covered Cerezyme and the dosage suggested by the doctor from the beginning. Last May, the Whitbecks received a confirmation letter that UnitedHealthcare would cover the drug.

Even then, though, the Whitbecks said they were required to get the coverage reauthorized at random intervals, ranging from three weeks to 10 weeks. And in late October 2016, fear struck the family when a letter arrived saying Luke’s medicine was reauthorized for just one week.

In an emailed statement, UnitedHealthcare said it granted a request in early November from Luke’s doctor to approve payment for a full year. The insurer declined multiple requests for interviews with executives. But Lempner stated in an email that “specialty medications like these are among the greatest drivers of pharmacy benefit costs for all employers, individuals, insurers and the government.”

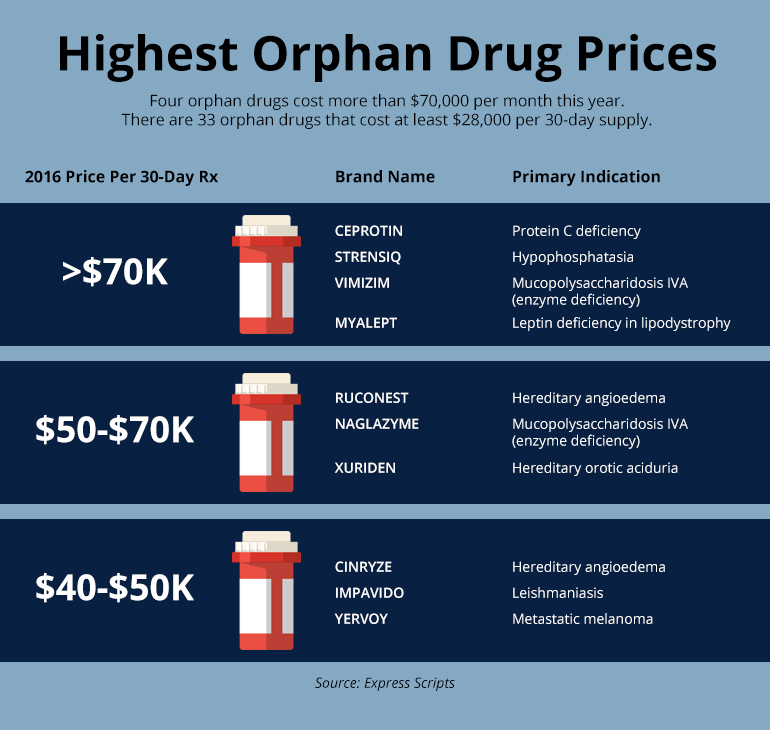

At the request of Kaiser Health News, Express Scripts, which manages pharmacy benefits, analyzed the orphan drugs on its approved list, or formulary. Four orphans cost more than $70,000 for a 30-day supply, or $840,000 annually. Another 29 orphan drugs cost at least $28,000 for a 30-day supply, or more than $336,000 a year. At those prices, the revenue for an orphan drugmaker can build up quickly: A $50,000 orphan taken by 50,000 patients could reach $2.5 billion in annual sales; a $300,000 orphan for just 5,000 people could hit $1.5 billion a year.

Just after Christmas, Biogen Inc. announced it would market Spinraza, its newly approved treatment for spinal muscular atrophy, for up to $750,000 in the first year and $375,000 in later years. Leerink analyst Geoffrey Porges wrote in a note that the price could be “the straw that breaks the camel’s back in terms of the U.S. market’s tolerance for rare disease pricing.”

Executives at Express Scripts, the pharmacy which supplies Luke’s medicine, said orphan drugs like Cerezyme often have very few competing drugs that could help them drive down the cost.

“We have very little negotiating power because the pharmaceutical company can set the price and we have to be a price acceptor,” said Dr. Steve Miller, chief medical officer for Express Scripts.

In the past year, the Whitbecks said they have paid more than $17,000 out of pocket for Luke’s medical care. Most of the cost falls on Oxford, the insurer that covers the 25 employees and their families where Drew works. The small company, owned by Meg’s side of the family, said the medical coverage for its employees amounts to about $338,000 a year and employees don’t pay monthly premiums.

The ultimate cost to the family is unclear but they fear the drug treatments, plus related care, could reach into hundreds of thousands per year if the reauthorizations ever stop.

Luke Whitbeck at the cardiology department at Maria Fareri Children’s Hospital in Hawthorne, N.Y., in October 2016. (Heidi de Marco/KHN)

Meg has gone back to work part time as a dietician and the family launched a fund-raising effort called “The Warrior Campaign” on social media, which shows the family has raised nearly $12,000 thus far. They also applied for $15,000 in aid from the Sanofi Genzyme’s patient assistance program. So far, the family said the company has paid for a month of Cerezyme and provided guidance from a case manager.

While she appreciates the support, Meg Whitbeck is daunted by the uncertainty of what the family has to come up with.

“We’re not going to not treat Luke, but we’re also never going to be able to pay these bills,” she said. “It was almost laughable.”

Much of the drug’s early development costs were paid for by the National Institutes of Health, according to a 1992 report from the congressional Office of Technology Assessment. The report notes that Genzyme spent about $29.4 million on R&D for the early version of the drug, Ceredase. The company quickly recovered those costs. Ceredase launched with a nearly $300,000 price tag in 1991 as one of the most expensive drugs in the world. Cerezyme, a genetically engineered successor, came to market in 1994. French pharmaceutical giant Sanofi-Aventis acquired Genzyme for $20.1 billion in 2011.

Sanofi Genzyme declined multiple requests for interviews. In an email, company spokeswoman Lisa Clemence said the company has raised the price of Cerezyme slightly since it launched and — relative to inflation, it’s 33 percent less expensive today than 22 years ago. Asked how drug prices are set, Clemence emailed that it is “determined by the clinical value they provide to patients and the rarity of the disease they treat.”

The Whitbeck family, Drew 35, Luke, 2, Parker, 5 and Meg, 34, at their home in Ridgefield, Conn., in October 2016. (Heidi de Marco/KHN)

Meg Whitbeck says their faith has helped the family cope with Luke’s diagnosis. (Heidi de Marco/KHN)

Cerezyme is still the drugmaker’s top-selling rare disease medicine, with nearly $800 million in 2015 annual sales, according to the French company’s annual financial filing. Despite competition, prices to treat Gaucher disease have not come down; indeed, the newest drugs on the market are priced at about $300,000 as well.

Drew Whitbeck joked that, in the end, it all feels like Monopoly money to him. Meg would like the company to justify Cerezyme’s price.

“I totally get from a scientific point of view, what it takes to create, manufacture and deliver these medications,” she said. “But why can’t they make it a little less expensive? What’s holding them back?”

“Specialty drugs,” which include orphan drugs, have seen “incredible price increases the past few years, across the board,” said Craig Burns, vice president for research at America’s Health Insurance Plans, which represents health insurers.

AHIP, in a study led by Burns, found that the prices of 45 orphan drugs increased 30 percent, on average, from 2012 through 2014.

Former U.S. Rep. James Greenwood, R-Pa., now president of the Biotechnology Innovation Organization, a trade group, said insurers are overstating the impact.

Meg and Luke Whitbeck wait to be seen by the cardiologist at Maria Fareri Children’s Hospital. (Heidi de Marco/KHN)

“The insurance industry likes to tell us that the reason our premiums [and] our copays and coinsurance are going up and our deductibles are going up” is because of high prices for orphans or other drugs, Greenwood said. “It just isn’t the case.” The bulk of health care spending, Greenwood said, is for hospitals, doctors and nursing homes. Prescription drugs get attention, he said, because “we are an easier target.”

Insurers, including UnitedHealthcare, try to mitigate the costs of orphans and other high-cost drugs by requiring patients to pay a larger share, setting quantity limits and asking patients to try other less expensive drugs first, a process known as step therapy.

Some believe that amounts to rationing.

“Nobody wants to talk about rationing, but there is already some of that anyway because of [the] levels of insurance that we have,” said Christopher-Paul Milne, director of research at Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development.

‘What Would God Really Think About This?’

Abbey Meyers, founder of NORD, National Organization for Rare Disorders (Courtesy of Abbey Meyers)

In the early 1980s, Abbey Meyers was known on Capitol Hill as the housewife from Connecticut — an angry mother who wouldn’t put up with pharmaceutical companies ignoring her son’s illness, Tourette syndrome.

A drugmaker had stopped producing medicine for the disorder, saying there weren’t enough patients to justify the cost. Meyers mobilized advocates, lawmakers and even actor Jack Klugman from the popular TV show “Quincy, M.E.” to persuade Congress to pass the Orphan Drug Act.

Under the law, companies with orphan drugs win some of the richest financial incentives in the regulatory world: a 50 percent tax credit on research and development in the U.S., fee waivers and access to federal grants. In a 2009 webinar, an FDA official referred to the incentive package as “our ‘basket of goodies.'”

Most important, once an orphan drug gains FDA approval, the agency guarantees it will not approve another version to treat that specific disease for seven years, even if the brand name company’s patent has run out.

Now, three decades since the program started, Meyers is worried that corporate greed is ruining her legacy.

“They will set a price of $300,000 a year for their drug for a fatal disease. And they’ll go to church every Sunday, and they will pray, and they’ll ask for God’s grace, you know?” Meyers said during an interview at her Connecticut home. “I’m wondering, what does God really think about this?”

Epilogue

Just before Christmas, the Whitbecks coped with another health scare.

There was a blockage in Luke’s chest port, an implanted catheter through which Cerezyme is delivered into his body each week. He needed surgery to fix it. Luke came down with pneumonia afterward but has recovered.

Luke, 2, has Gaucher disease, a rare hereditary condition, and needs a weekly enzyme infusion of an orphan drug to treat the disorder. (Heidi de Marco/KHN)

“I hope in 2017 there are no hospital admissions,” Meg Whitbeck said. Then she paused and recalled that the family hadn’t yet seen all the bills from the port surgery.

The family’s savings disappeared in 2016. And the Whitbecks are still trying to figure out if they have to pay an outstanding $6,000 bill for Cerezyme that appeared on the latest pharmacy statement.

“We’re not scared,” Whitbeck said, but “when you’re a parent of a child with a chronic illness, you’re always walking on a tight rope … Every day we have to give [Luke] the once-over and make sure everything is good. If it’s a good day, everything is like a normal family.”

Contributors: John Hillkirk, Scott Hensley, NPR, Diane Webber (editors); Elizabeth Lucas (data editing); Joe Neel, NPR (radio editing)

Interactives, Video and Presentation: Lydia Zuraw, Emily Kopp and Meredith Rizzo, NPR (timeline, digital presentation); Francis Ying (videos, motion graphic); Heidi de Marco (videos, photos); Alley Interactive (database lookup)

KHN’s coverage of prescription drug development, costs and pricing is supported in part by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation.