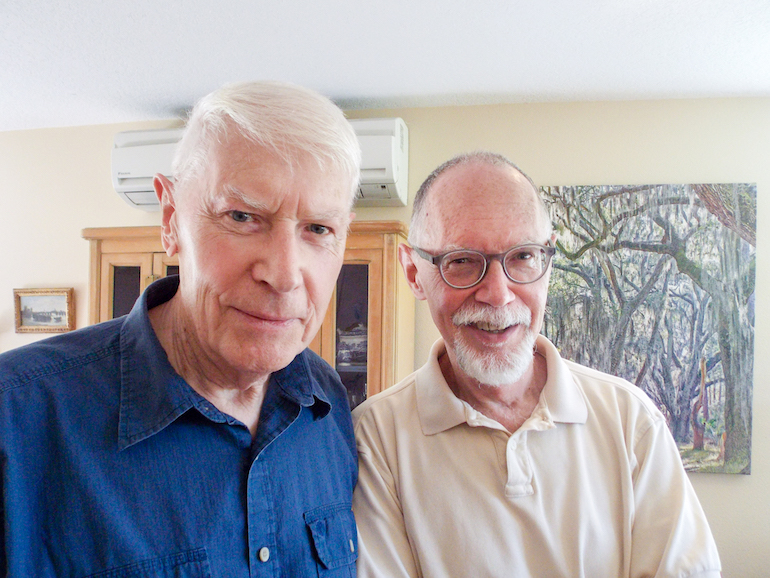

Partners Edwin Fisher, 86, and Patrick Mizelle, 64, moved to Rose Villa in Portland, Oregon, from Georgia about three years ago. Fisher and Mizelle worried residents of senior living communities in Georgia wouldn’t accept their gay lifestyle. (Anna Gorman/KHN)

Patrick Mizelle and Edwin Fisher, who have been together for 37 years, were planning to grow old in their home state of Georgia.

But visits to senior living communities left them worried that after decades of living openly, marching in pride parades and raising money for gay causes, they wouldn’t feel as free in their later years. Fisher said the places all seemed very “churchy,” and the couple worried about evangelical people leaving Bibles on their doorstep or not accepting them.

“I thought, ‘Have I come this far only to have to go back in the closet and pretend we are brothers?” said Mizelle. “We have always been out and we didn’t want to be stuck in a place where we couldn’t be.”

So three years ago, they moved across the country to Rose Villa, a hillside senior living complex just outside of Portland that actively reaches out to gay, lesbian and transgender seniors.

As openly gay and lesbian people age, they will increasingly rely on caregivers and move into assisted living communities and nursing homes. And while many rely on friends and partners, more are likely to be single and without adult children, according to research published by the National Institutes of Health.

Rose Villa Senior Living, located just outside of Portland, Oregon, has made a point of welcoming LGBT elders. The community, which offers independent and assisted living, also has a nursing home on site. (Anna Gorman/KHN)

But long-term care facilities frequently lack trained staff and policies to discourage discrimination, advocates and doctors said. That can lead to painful decisions for seniors about whether to hide their sexual orientation or face possible harassment by fellow elderly residents or caregivers with traditional views on sexuality and marriage.

“It is a very serious challenge for many LGBT older people,” said Michael Adams, chief executive officer of SAGE, or Services and Advocacy for Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Elders. “[They] really fought to create a world where people could be out and proud. … Now our LGBT pioneers are sharing residences with those who harbor the most bias against them.”

There are an estimated 1.5 million gay, lesbian and bisexual people over 65 living in the U.S. currently, and that number is expected to double by 2030, according to the organization, which runs a national resource center on LGBT aging.

Nationwide, advocacy groups are pushing to improve conditions and expand options for gay and lesbian seniors. Facilities for LGBT seniors have opened in Chicago, Philadelphia, San Francisco and elsewhere.

SAGE staff are also training providers at nursing homes and elsewhere to provide a more supportive environment for elderly gays and lesbians. That may mean asking different questions at intake, such as whether they have a partner rather than if they are married (even though they can get married, not all older couples have). Or it could be a matter of educating other residents and offering activities specific to the LGBT community like gay-friendly movies or lectures.

Mizelle, 64, and Fisher, 86, said they found the support they hoped for at Rose Villa, where they live in a ground-floor cottage near the community garden and spend their time socializing with other residents, both gay and straight. They both exercise in the on-site gym and pool. Fisher bakes for a farmer’s market and Mizelle is participating in art classes. Fisher, who recently had a few small strokes, said they liked Rose Villa for another reason too: It provides in-home caregivers and has a nursing facility on site.

But many aging gays and lesbians — the generation that protested for gay rights at Stonewall, in state capitols and on the steps of the Supreme Court — may not be living in such welcoming environments. Only 20 percent of LGBT seniors in long-term care facilities said they were comfortable being open about their sexual orientation, according to a recent report by Justice in Aging, a national nonprofit legal advocacy organization.

Ed Dehag, 70, at the Triangle Square Apartments in Los Angeles in August 2016. The retired floral designer moved into the building when his partner passed away and he couldn’t afford the rent on his old apartment by himself. (Heidi de Marco/KHN)

This summer, Lambda Legal, a gay advocacy group, filed a lawsuit against the Glen Saint Andrew Living Community, a senior residential facility in Niles, Illinois, for failing to protect a disabled lesbian woman from harassment, discrimination and violence. The resident, 68-year-old Marsha Wetzel, moved into the complex in 2014 after her partner of 30 years had died of cancer. Soon after, residents called her names and even physically assaulted her, according to the lawsuit.

“I don’t feel safe in my own home,” Wetzel said in a phone interview. “I am scared constantly. … What I am doing is about getting justice. I don’t want other LGBT seniors to go through what I’ve gone through.”

Karen Loewy, Wetzel’s attorney at Lambda Legal, said senior living facilities are “totally ill-prepared” for this population of openly gay elders. She said she hopes the case will not only stop the discrimination against Wetzel but will start a national conversation.

“LGBT seniors have the right to age with dignity and free from discrimination, and we want senior living facilities to know … that they have an obligation to protect it,” Loewy said.

A photo of Dehag’s partner sits on the dresser in his bedroom. Dehag moved into one of the apartments shortly after his partner passed away. (Heidi de Marco/KHN)

Spencer Maus, spokesman for Glen Saint Andrew, declined to comment specifically on the lawsuit but said in an email that the community “does not tolerate discrimination of any kind or under any circumstances.”

Many elderly gay and lesbian people have difficulty finding housing at all, according to a 2010 report by several advocacy organizations in partnership with the federal American Society on Aging. Another report in 2014 by the Equal Rights Center, a national nonprofit civil rights organization, revealed that the application process was more difficult and housing more expensive for gay and lesbian seniors.

Recognizing the need for more affordable housing, the Los Angeles Gay & Lesbian Elder Housing organization opened Triangle Square Apartments in 2007. In the building, the first of its kind, residents can get health and social services through the Los Angeles LGBT Center. The wait for apartments with the biggest subsidies is about five years.

Residents display rainbow flags outside their doors throughout the building. On a recent morning, fliers about falls, mental health, movie nights and meningitis vaccines were posted on a bulletin board near the elevator.

Lee Marquardt, 74, at the Triangle Square Apartments in Los Angeles, California, in August 2016. Marquardt moved into the apartment building two years ago. She said she didn’t want to spend her elder years hiding her true self as she had as a younger woman. (Heidi de Marco/KHN)

Ed Dehay, 80, moved into one of the apartments when they first opened. His partner had recently passed away and he couldn’t afford the rent on his old apartment by himself. “This was a godsend for me,” said Dehay, a retired floral designer who has covered every wall of his apartment with framed art.

His neighbor, 74-year-old Lee Marquardt, said she came out after raising three children, and didn’t want to spend her elder years hiding her true self as she had as a younger woman. Marquardt, a former truck driver who has high blood pressure and kidney disease, said she found a new family as soon as she moved into the apartment building two years ago.

“I was dishonest all the time before,” she said. “Now I am who I am and I don’t have to be quiet about it.”

Tanya Witt, resident services coordinator for the Los Angeles LGBT Center, said some of the Triangle Square residents are reluctant to have in-home caregivers — even in their current housing — because they worry they won’t be gay-friendly. Others say they won’t ever go into a nursing home, even if they have serious health needs.

Marquardt holds an old photograph of herself of when she was married. Marquardt, a former truck driver who has high blood pressure and kidney disease, came out after raising three children. (Heidi de Marco/KHN)

In addition to facing common health problems as they age, gay and lesbian seniors also may be dealing with additional stressors, isolation or depression, said Alexia Torke, an associate professor of medicine at Indiana University.

“LGBT older adults have specific needs in their health care,” she said. And caregivers “need to be aware.”

Lesbian, gay and bisexual elders are at higher risk of mental health problems and disabilities and have higher rates of smoking and excessive alcohol consumption. They are also more likely to delay health care, according to a report by The Williams Institute at UCLA School of Law. In addition, older gay men are disproportionately affected by some chronic diseases, including hypertension, according to research out of UCLA.

Torke said LGBT seniors are not strangers to nursing homes. The difference now is that there is a growing recognition of the need to make the homes safe and welcoming for them, she said.

The Los Angeles Gay and Lesbian Elder Housing organization opened Triangle Square Apartments in 2007. In the first of its kind building, residents can get health and social services through the Los Angeles LGBT Center. (Heidi de Marco/KHN)

At Rose Villa, CEO Vassar Byrd said she began working nearly a decade ago to make the community more open to gays after a lesbian couple told her that another facility had suggested they would be more welcome if they posed as sisters. Today, several gay, lesbian and transgender people — individually and in couples — are living there, Byrd said. Her staff has undergone training to help them better care for that population, and Byrd said she has spoken to other senior care providers around the nation about the issue.

Bill Cunitz and Lee Nolet, who began dating in 1976, didn’t come out as a couple until they moved to Rose Villa last year. Cunitz is an ordained minister and former head of a senior living community in Southern California. He said he didn’t want to be known as the “gay CEO.”

Nolet, a retired nurse and county health official, said it’s been “absolutely amazing” to find a place where they can be open— and where they know they will have accepting people who can take care of them if they get sick.

“After 40 years of being in the shadows … we introduce each other as partner,” Nolet said. “Everyone here knows we’re together.”

KHN’s coverage of aging and long-term care issues is supported by The SCAN Foundation. KHN’s coverage in California is funded in part by Blue Shield of California Foundation.