Earlier this month, a day after the House of Representatives passed a bill to repeal and replace major parts of the Affordable Care Act, Ashleigh Morley visited her congressman’s Facebook page to voice her dismay.

“Your vote yesterday was unthinkably irresponsible and does not begin to account for the thousands of constituents in your district who rely upon many of the services and provisions provided for them by the ACA,” Morley wrote on the page affiliated with the campaign of Rep. Pete King (R-N.Y.). “You never had my vote and this confirms why.”

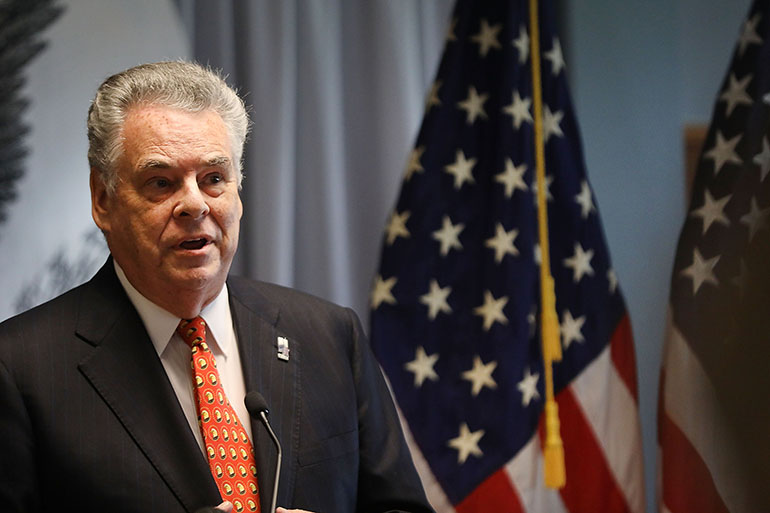

The next day, Morley said, her comment was deleted and she was blocked from commenting on or reacting to King’s posts. The same thing has happened to others critical of King’s positions on health care and other matters. King has deleted negative feedback and blocked critics from his Facebook page, say several of his constituents who shared screenshots of comments that are no longer there.

“Having my voice and opinions shut down by the person who represents me — especially when my voice and opinion wasn’t vulgar and obscene — is frustrating, it’s disheartening, and I think it points to perhaps a larger problem with our representatives and maybe their priorities,” Morley said in an interview.

King’s office did not respond to requests for comment.

As Republican members of Congress seek to roll back the Affordable Care Act (ACA), commonly called Obamacare, and replace it with the American Health Care Act (AHCA), they have adopted various strategies to influence and cope with public opinion, which, polls show, mostly opposes their plan. ProPublica, with our partners at Kaiser Health News, Stat and Vox, has been fact-checking members of Congress in this debate and we’ve found misstatements on both sides, though more by Republicans than Democrats. The Washington Post’s Fact Checker has similarly found misstatements by both sides.

Today, we’re back with more examples of how legislators are interacting with constituents about repealing Obamacare, whether online or in traditional correspondence. Their more controversial tactics seem to fall into three main categories: providing incorrect information, using euphemisms for the impact of their actions and deleting comments critical of them. (Share your correspondence with members of Congress with us.)

Incorrect Information

Rep. Vicky Hartzler (R-Mo.) sent a note to constituents this month explaining her vote in favor of the Republican bill. First, she outlined why she believes the ACA is not sustainable — namely, higher premiums and few choices. Then she said it was important to have a smooth transition from one system to another.

“This is why I supported the AHCA to follow through on our promise to have an immediate replacement ready to go should the ACA be repealed,” she wrote. “The AHCA keeps the ACA for the next three years then phases in a new approach to give people, states, and insurance markets plenty of time to make adjustments.”

Except that’s not true.

“There are quite a number of changes in the AHCA that take effect within the next three years,” wrote ACA expert Timothy Jost, an emeritus professor at Washington and Lee University School of Law, in an email to ProPublica.

The current law’s penalties on individuals who do not purchase insurance and on employers who do not offer it would be repealed retroactively to 2016, which could remove the incentive for some employers to offer coverage to their workers. Moreover, beginning in 2018, older people could be charged premiums up to five times more than younger people — up from three times under current law. The way in which premium tax credits would be calculated would change as well, benefiting younger people at the expense of older ones, Jost said.

“It is certainly not correct to say that everything stays the same for the next three years,” he wrote.

In an email, Hartzler spokesman Casey Harper replied, “I can see how this sentence in the letter could be misconstrued. It’s very important to the Congresswoman that we give clear, accurate information to her constituents. Thanks for pointing that out.”

Other lawmakers have similarly shared incorrect information after voting to repeal the ACA. Rep. Diane Black (R-Tenn.) wrote in a May 19 email to a constituent that “in 16 of our counties, there are no plans available at all. This system is crumbling before our eyes and we cannot wait another year to act.”

Black was referring to the possibility that, in 16 Tennessee counties around Knoxville, there might not have been any insurance options in the ACA marketplace next year. However, 10 days earlier, before she sent her email, BlueCross BlueShield of Tennessee announced that it was willing to provide coverage in those counties and would work with the state Department of Commerce and Insurance “to set the right conditions that would allow our return.”

“We stand by our statement of the facts, and Congressman Black is working hard to repeal and replace Obamacare with a system that actually works for Tennessee families and individuals,” her deputy chief of staff Dean Thompson said in an email.

On the Democratic side, The Washington Post Fact Checker has called out representatives for saying the AHCA would consider rape or sexual assault as preexisting conditions. The bill would not do that, although critics counter that any resulting mental health issues or sexually transmitted diseases could be considered existing illnesses.

Euphemisms

A number of lawmakers have posted information taken from talking points put out by the House Republican Conference that try to frame the changes in the Republican bill as kinder and gentler than most experts expect them to be.

An answer to one frequently asked question pushes back against criticism that the Republican bill would gut Medicaid, the federal-state health insurance program for the poor, and appears on the websites of Rep. Garret Graves (R-La.) and others.

“Our plan responsibly unwinds Obamacare’s Medicaid expansion,” the answer says. “We freeze enrollment and allow natural turnover in the Medicaid program as beneficiaries see their life circumstances change. This strategy is both fiscally responsible and fair, ensuring we don’t pull the rug out on anyone while also ending the Obamacare expansion that unfairly prioritizes able-bodied working adults over the most vulnerable.”

That is highly misleading, experts say.

The Affordable Care Act allowed states to expand Medicaid eligibility to anyone who earned less than 138 percent of the federal poverty level, with the federal government picking up almost the entire tab. Thirty-one states and the District of Columbia opted to do so. As a result, the program now covers more than 74 million beneficiaries, nearly 17 million more than it did at the end of 2013.

The GOP health care bill would pare that back. Beginning in 2020, it would reduce the share the federal government pays for new enrollees in the Medicaid expansion to the rate it pays for other enrollees in the state, which is considerably less. Also in 2020, the legislation would cap the spending growth rate per Medicaid beneficiary. As a result, a Congressional Budget Office review released Wednesday estimates that millions of Americans would become uninsured.

Sara Rosenbaum, a professor of health law and policy at the Milken Institute School of Public Health at George Washington University, said the GOP’s characterization of its Medicaid plan is wrong on many levels. People naturally cycle on and off Medicaid, she said, often because of temporary events not changing life circumstances — seasonal workers, for instance, may see their wages rise in summer months before falling back.

“A terrible blow to millions of poor people is recast as an easing off of benefits that really aren’t all that important, in a humane way,” she said.

Moreover, the GOP bill actually would speed up the “natural turnover” in the Medicaid program, said Diane Rowland, executive vice president of the Kaiser Family Foundation, a health care think tank. (Kaiser Health News is an editorially independent project of KFF.)

Under the ACA, states were permitted only to recheck enrollees’ eligibility for Medicaid once a year because cumbersome paperwork requirements have been shown to cause people to lose their coverage. The American Health Care Act would require these checks every six months — and even give states more money to conduct them.

Rowland also took issue with the GOP talking point that the expansion “unfairly prioritizes able-bodied working adults over the most vulnerable.” At a House Energy and Commerce Committee hearing earlier this year, GOP representatives maintained that the Medicaid expansion may be creating longer waits for home- and community-based programs for sick and disabled Medicaid patients needing long-term care, “putting care for some of the most vulnerable Americans at risk.”

Research from the Kaiser Family Foundation, however, showed that there was no relationship between waiting lists and states that expanded Medicaid. Such waiting lists predated the expansion and they were worse in states that did not expand Medicaid than in states that did.

“This is a complete misrepresentation of the facts,” Rosenbaum said.

Graves’ office said the information on his site came from the House Republican Conference. Emails to the conference’s press office were not returned.

The GOP talking points also play up a new Patient and State Stability Fund included in the AHCA, which is intended to defray the costs of covering people with expensive health conditions. “All told, $130 billion dollars would be made available to states to finance innovative programs to address their unique patient populations,” the information says. “This new stability fund ensures these programs have the necessary funding to protect patients while also giving states the ability to design insurance markets that will lower costs and increase choice.”

The fund was modeled after a program in Maine, called an invisible high-risk pool, which advocates say has kept premiums in check in the state. But Sen. Susan Collins (R-Maine) says the House bill’s stability fund wasn’t allocated enough money to keep premiums stable.

“In order to do the Maine model — which I’ve heard many House people say that is what they’re aiming for — it would take $15 billion in the first year and that is not in the House bill,” Collins told Politico. “There is actually $3 billion specifically designated for high-risk pools in the first year.”

Deleting Comments

Morley, 28, a branded content editor who lives in Seaford, N.Y., said she moved into Rep. King’s Long Island district shortly before the 2016 election. She said she did not vote for him and, like many others across the country, said the election results galvanized her into becoming more politically active.

Earlier this year, Morley found an online conversation among King’s constituents who said their critical comments were being deleted from his Facebook page. Because she doesn’t agree with King’s stances, she said she wanted to reserve her comment for an issue she felt strongly about.

A day after the House voted to repeal the ACA, Morley posted her thoughts. “I kind of felt that that was when I wanted to use my one comment, my one strike as it would be,” she said.

By noon the next day, it had been deleted and she had been blocked.

“I even wrote in my comment that you can block me but I’m still going to call your office,” Morley said in an interview.

Some negative comments about King remain on his Facebook page. But King’s critics say his deletions fit a broader pattern. He has declined to hold an in-person town hall meeting this year, saying, “to me all they do is just turn into a screaming session,” according to CNN. He held a telephonic town hall meeting but answered only a small fraction of the questions submitted. And he met with Liuba Grechen Shirley, the founder of a local Democratic group in his district, but only after her group held a protest in front of his office that drew around 400 people.

“He’s not losing his health care,” Grechen Shirley said. “It doesn’t affect him. It’s a death sentence for many, and he doesn’t even care enough to meet with his constituents.”

King’s deleted comments even caught the eye of Andy Slavitt, who until January was the acting administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Slavitt has been traveling the country pushing back against attempts to gut the ACA.

.@RepPeteKing, are you silencing your constituents who send you questions?

Assume ppl in district will respond if this is happening.

— Andy Slavitt 🇮🇱 🇺🇦 (@ASlavitt) May 12, 2017

Since the election, other activists across the country who oppose the president’s agenda have posted online that they have been blocked from following their elected officials on Twitter or commenting on their Facebook pages because of critical statements they’ve made about the AHCA and other issues.

Have you corresponded with a member of Congress or senator about the Affordable Care Act? Or has your comment on an elected official’s Facebook page been deleted? We’d love to hear about it. Please fill out our short form or email charles.ornstein@propublica.org.