The number of people with insurance coverage for alcohol and drug abuse disorders is about to explode at a time there’s already a severe shortage of trained behavioral health professionals in many states.

Until now, there’s been no data on just how severe the shortage is and where it’s most dire. Jeff Zornitsky of the health care consulting firm Advocates for Human Potential (AHP) has developed the first measurement of how many behavioral health professionals are available to treat millions of adults with a substance use disorder, or SUD, in all 50 states.

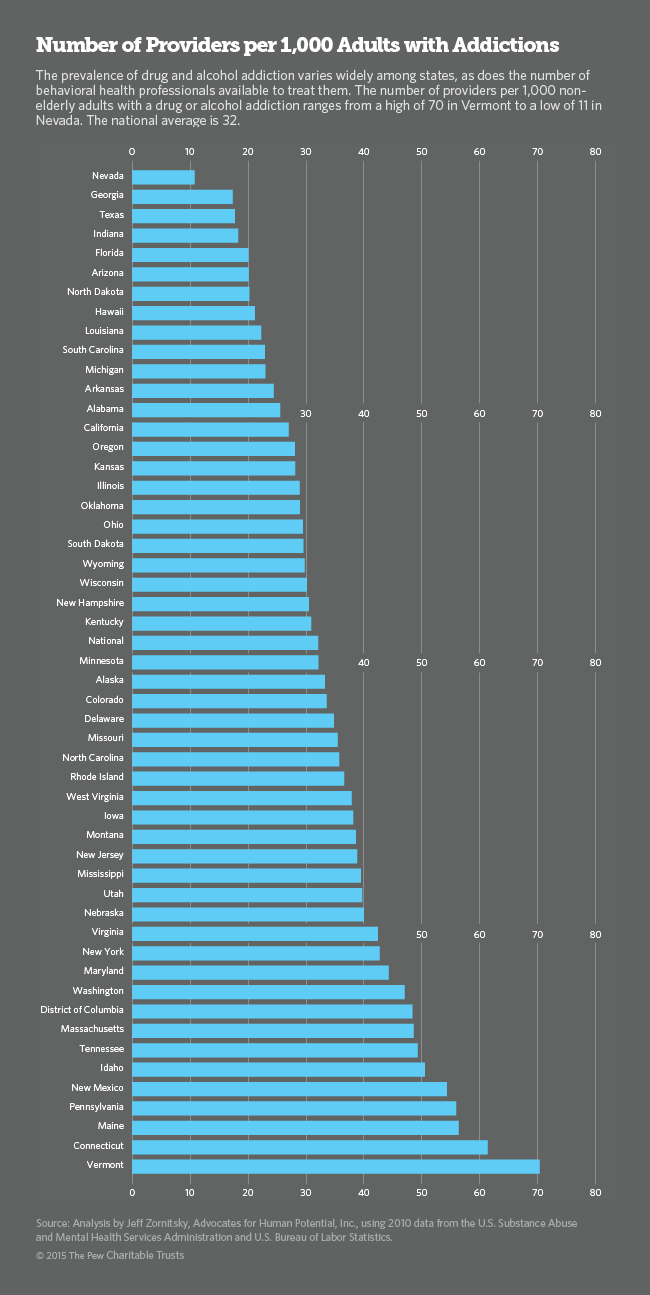

Zornitsky’s “provider availability index” – the number of psychiatrists, psychologists, counselors and social workers available to treat every 1,000 people with SUD – ranges from a high of 70 in Vermont to a low of 11 in Nevada. Nationally, the average is 32 behavioral health specialists for every 1,000 people afflicted with the disorder. No one has determined what the ideal number of providers should be, but experts agree the current workforce is inadequate in most parts of the country.

“Right now we’re in a severe workforce crisis,” said Becky Vaughn, addictions director for the industry organization National Council for Behavioral Health. The shortage has consequences, she said. “When people need help for addictions, they need it right away. There’s no such thing as a waiting list. If you put someone on a waiting list, you won’t be able to find them the next day.”

The shortage of specialists threatens to stall a national movement to bring the prevention and treatment of SUD into the mainstream of American medicine at a time when millions of people with addictions have a greater ability to pay for treatment thanks to insurance.

Two Federal Laws

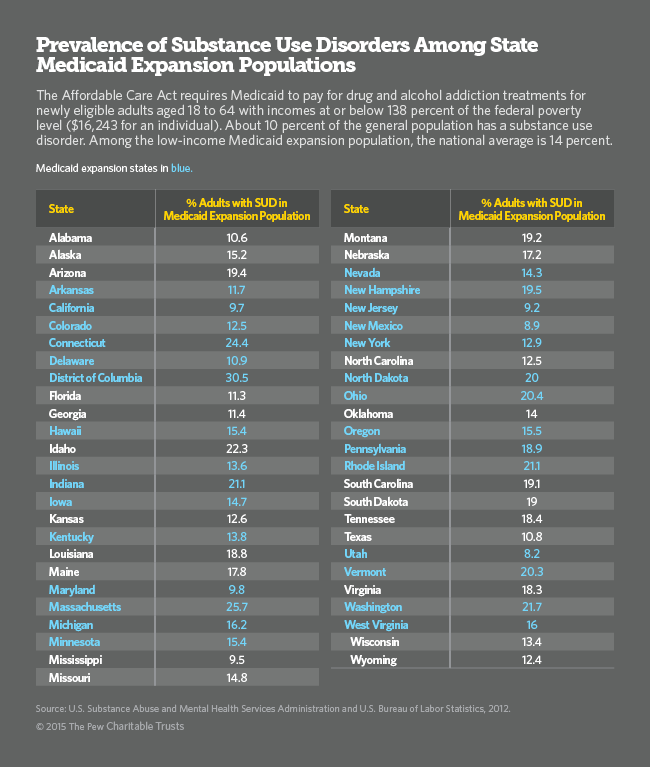

The Affordable Care Act for the first time requires all insurers, including Medicaid, to cover the treatment of drug and alcohol addiction. In the past, Medicaid covered only pregnant women and adolescents in most states. Private insurance either didn’t pay for treatments or paid so little that most people could not afford to make up the difference.

For anyone with insurance coverage, the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act ensures that the duration and dollar amount of coverage for substance use disorders is comparable to coverage for medical and surgical care. Together, the two federal laws are expected to make billions of dollars available to the behavioral health care market.

Of the estimated 18 million adults potentially eligible for Medicaid in all 50 states, at least 2.5 million have substance use disorders. Of the 19 million uninsured adults with slightly higher incomes who are eligible for subsidized exchange insurance, an estimated 2.8 million struggle with substance abuse, according to the most recent national survey by the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Although the federal government has acknowledged the scarcity of treatment specialists, it has failed to quantify and assess it. Other fields of health care, including mental health and primary care, are tracked by the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration to determine which communities are “underserved.” Without this information, it is hard to know where more behavioral health specialists are needed and when the supply of providers is expanding or shrinking in any given region.

That’s where AHP’s Zornitsky steps in. Using data from the U.S. Department of Labor’s Bureau of Labor Statistics on the current size of the labor force and its projected growth, plus Department of Health and Human Services data on the prevalence of SUD among adults, he approximates the relative adequacy of the addiction treatment workforce in each state.

“It is not perfect,” Zornitsky said of the index, “but it’s a consistent, state-based measure that allows for comparisons and tracking over time.”

Poor Pay

According to a 2013 report to Congress from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the “growing workforce crisis in the addictions field” is due to a variety of factors, including stigma, an aging workforce and inadequate compensation.

The U.S. spent $24 billion on treatment of drug and alcohol disorders in 2009, the most recent year for which comprehensive data are available, according to a new study by the Pew Charitable Trusts (Pew also funds Stateline). Sixty-nine percent of the spending came from public sources such as state and local governments, Medicaid, Medicare and federal grants. Private sources, including commercial insurance and out-of-pocket spending, made up the balance, according to the report.

Historically, reimbursement rates and consequently salaries for physicians, psychologists, social workers and counselors in the addiction field have been well below salaries for comparable professionals in other health care specialties that require the same level of education and training.

For example, the average salary for social workers in the addiction field is $38,600, compared to $47,230 in the rest of the health care industry, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

As a result, too few health care workers are going into the field and too many are switching to more lucrative specialties. And because the average age of addiction specialists is higher than in other professions, demographers predict a behavioral health retirement boom in the next five years.

Between now and 2020, the addiction services field will need to fill more than 330,000 jobs to keep pace with demand, of which more than half are the result of people retiring and switching to other occupations.

Low Treatment Rates

Of the roughly 23 million Americans who suffer from drug and alcohol disorders, only 11 percent receive treatment at a specialty facility, according to the most recent National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

That compares to U.S. treatment rates as high as 80 percent for diseases such as diabetes and hypertension. Part of the reason for lack of treatment has been inability to pay. With billions in private insurance and Medicaid dollars becoming available, that is expected to change.

But questions remain about how the existing addiction services industry will manage the expansion, whether new businesses will enter the market and how many providers will take Medicaid patients. Today, only 55 percent of addiction practitioners accept Medicaid reimbursements, which tend to be lower than private insurance.

Another reason many substance abusers go without treatment is the social stigma connected with addictions and mental illness. To avoid being labeled, many hide their drug or alcohol use, and refuse to admit they have a problem. With more money available for treatment and increased public concern over the nation’s rising death toll from drug addictions, experts are hopeful the stigma will dissipate and more health care professionals will be drawn to the field.

The Affordable Care Act eventually should spur more competitive salaries for behavioral health professionals. But for now, it is complicating matters, Vaughn said. Both Medicaid and private insurers require levels of professional licensing and credentialing that were not needed when addiction services were funded primarily by federal grants. In addition, many of the mostly small providers in the industry have no business experience negotiating contracts with Medicaid managed care organizations or filing claims for Medicaid and private insurance.

It will be largely up to states to make the changes needed to develop an adequate addiction treatment workforce. The federal government has offered model licensing guidelines that define a so-called “scope of practice” for each job title in the behavioral health profession, but states will have to create licensing laws and regulations. States could also encourage more people to go into the profession by offering to repay student loans and funding local colleges.

In addition, state Medicaid agencies will need to reach out to the existing addiction industry and provide business training to enable them to file claims for the billions in new funding for drug and alcohol treatments. Most important, Vaughn said, Medicaid rates for addiction services need to be raised to provide a reimbursement benchmark that is closer to the fees paid to practitioners in other health care professions.