To start a lively discussion of America’s health care system, let’s consider who’s responsible for saving the sight of Luis Lang.

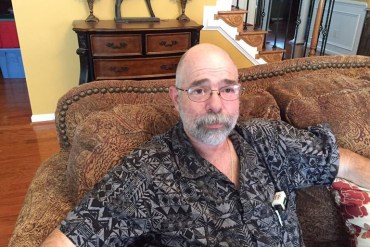

Luis Lang, an uninsured resident of Fort Mill, S.C., needs an expensive operation to save his sight. (Ann Doss Helms, Charlotte Observer)

Lang, a 49-year-old resident of Fort Mill, S.C., has bleeding in his eyes and a partially detached retina caused by diabetes.

“He will lose his eyesight if he doesn’t get care. He will go blind,” said Dr. Malcolm Edwards, the Lancaster ophthalmologist who examined Lang.

Lang is a self-employed handyman who works with banks and the federal government on maintaining foreclosed properties. He has done well enough that his wife, Mary, hasn’t had to work. They live in a 3,300-square-foot home in the Legacy Park subdivision valued at more than $300,000.

But he has never bought insurance. Instead, he says, he prided himself on paying his own medical bills.

That worked while he and his wife were relatively healthy. But after 10 days of an unrelenting headache, Lang went to the emergency room on Feb. 25. He says he was told he’d suffered several ministrokes. He ran up $9,000 in bills and exhausted his savings. Meanwhile, his vision worsened, and he can’t work, he says.

That’s when he turned to the Affordable Care Act exchange. Lang learned two things: First, 2015 enrollment had closed earlier that month. And second, because his income has dried up, he earns too little to get a federal subsidy to buy a private policy.

Lang, a Republican, says he knew the act required him to get coverage, but he chose not to do so. But he thought help would be available in an emergency. He and his wife blame President Barack Obama and congressional Democrats for passing a complex and flawed bill.

“(My husband) should be at the front of the line, because he doesn’t work and because he has medical issues,” Mary Lang said last week. “We call it the Not Fair Health Care Act.”

Anyone who’s remotely familiar with insurance knows there’s no system that lets people skip payments while they’re healthy and cash in when they get sick. Public systems tax everyone. Private ones rely on the premiums of the well to cover the costs of those who are ailing.

And Democrats might point out that the ACA was designed to provide Medicaid coverage for people whose income falls below the poverty line. The federal government pays 100 percent of the ACA expansion to cover low-income, able-bodied adults, but 21 Republican-led states, including North Carolina and South Carolina, declined to participate.

For now, Lang qualifies only for a South Carolina Medicaid plan that covers checkups and family planning. The aged (65 and older), blind and disabled get more extensive coverage. Lang says he hasn’t applied for Social Security disability benefits because it takes too long.

The S.C. Department of Health and Human Services is still reviewing whether he might qualify through a vocational rehabilitation program. If so – and if he can find a surgeon who takes Medicaid – South Carolina taxpayers will share the cost with the federal government.

Last week, Lang went back to Dr. Edwards, who had previously provided injections to control the bleeding in his eyes at a discounted rate. That’s when he learned that his problem had worsened, including the detached retina.

“He’s in a very bad situation,” Edwards said after Lang signed a privacy release. “The longer he waits, the poorer his results will be.”

Edwards said he would provide care at no cost, but Lang now requires surgery and follow-up treatment that is beyond his expertise. His Eye & Laser Center has a network of specialists who work on a sliding scale and organizations that sometimes help with donations. But Lang requires such extensive and ongoing work that there’s no way to guarantee there won’t be significant bills, Edwards said.

Lang says he has called charities that work with diabetes and blindness, but he doesn’t seem to fit anyone’s cause. “I’m either too young or too old,” said Lang, who has launched a GoFundMe.com page in hopes of garnering donations.

There’s a lot of talk about personal responsibility in health care reform, so it’s probably fair to note that Lang is a smoker who has, by his own account, been inconsistent in his efforts to control his diabetes. Edwards says it’s not uncommon to see patients who don’t take the treatment regimen seriously until they’re facing major problems. Bleeding in the blood vessels of the eyes often foretells similar problems with the kidneys and feet, he said.

When I started covering health care last summer, Newsday columnist Lane Filler wrote a column that was striking in its candor. He argued for employers to get out of the health insurance business, shift the money they spend on premiums into employee wages and give everyone the freedom to decide whether they’ll spend it on insurance.

“If I were just free, I could buy no health insurance, instead banking the money to pay medical bills as they came due,” Filler wrote. “But ‘just free’ societies must have onerous consequences for the imprudent and the unlucky. If we want to be allowed to buy health insurance or not, we must be willing to let folks who choose wrong be bankrupted by medical bills. Worse, we must be willing to let them die for lack of care, and listen to them wail from the gutters.”

That kind of argument can be easy to defend in an intellectual debate and hard to hold on to when you’re face to face with someone who’s going to die – or go blind – when they could be saved.

On the other side, you have single-payer advocates who say it’s time to stop arguing over who deserves to be denied coverage or care. Instead, they say, it’s time to treat health care like fire and police protection: Tax everyone and provide the aid when it’s needed.

Lang’s story drew national attention after it was posted on charlotteobserver.com Tuesday morning. Liberal bloggers across the country blasted him for blaming Obama for problems created by his own actions and South Carolina legislators. His fundraising page, which had gotten no donations in the first 24 days, raised more than $2,000 in the first 11 hours after the post went online. Most of it was small amounts from self-identified liberals and ACA supporters, who urged him to change his views.

“You’re a poster child for what you claim to be against, and like most of the donors here, I don’t believe ANYone deserves to suffer without proper medical care,” wrote Andrew Knight, who gave $5. “I wish you all the best. I hope you’ll come to see ACA and healthcare for all as a basic right.”

A staffer with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services emailed the Observer to say Lang’s case had been “discussed here in DC at a fairly high level” in hopes of finding a solution. If the family income were to rise above the poverty level ($15,730 for a couple), he could qualify for special enrollment, the staffer said.

For Lang’s doctor, the overwhelming feeling is frustration at knowing that one of his patients could lose his sight for lack of a way to pay for care that’s readily available in modern American society.

“That’s probably the worst thing that can happen to someone outside of death,” Edwards said. And he added that if Lang doesn’t get help now, he’s likely to end up dependent on the government: “It’s extremely costly to let a person go blind.”

This blog post comes from The Charlotte Observer, produced in partnership with KHN.