With covid vaccines expected to remain scarce into early spring, Connecticut has scrapped its complicated plans to prioritize immunizations for people under 65 with certain chronic conditions and front-line workers. Instead, the state will primarily base eligibility on age.

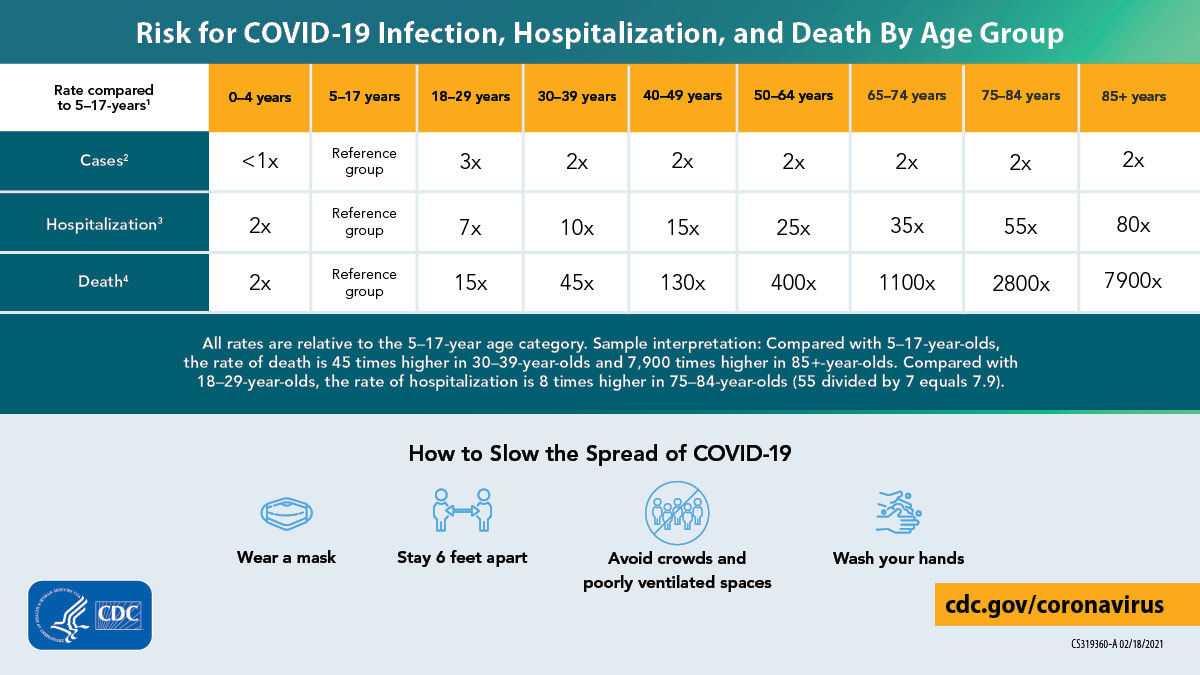

Gov. Ned Lamont pointed to statistics showing the risk of death and hospitalization from covid-19 rises significantly by age.

Yet, shifting to an age-based priority system — after health workers, nursing home patients and people 65 and up have been offered vaccines — has frustrated people with health conditions such as cancer or diabetes who thought they would be next in line. It also could exacerbate the difficulty in getting people in underserved communities and those in minority racial and ethnic groups vaccinated, health experts said.

While it’s reasonable for states to want to vaccinate people in their 50s and 60s ahead of those in their teens and 20s, the experts added, there are no easy answers in deciding who should get vaccines first. Is a 40-year-old with diabetes at higher risk than a 64-year-old without serious health issues? How about an older person who works at home or a younger person whose job puts them at higher risk of infection?

Gini Fischer, 57, a portrait artist in Wilton, Connecticut, has mixed feeling about people her age being in line ahead of those with chronic illnesses. She also teaches water aerobics to seniors at her local YMCA and sees getting vaccinated as a way to protect others. So, she plans to make an appointment for the vaccine.

“I do think people with chronic illnesses are more vulnerable than I am,” said Fischer, a breast cancer survivor. But given her teaching responsibilities, “I certainly don’t want to be a risk to anyone in the class,” she said. “I do believe the more people who get vaccinated the safer it will be for others who have not been vaccinated.”

People 50 to 64 are nine times more likely to die of the virus than adults 30 to 39, according to the data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“There’s no magic bullet,” said Claire Hannan, executive director of the Association of Immunization Managers, referring to the different priority lists.

Under Connecticut’s new plan, the state on Monday will be the first to start vaccinating everyone age 55 to 64 and up. Later this spring, the state plans to vaccine younger adults. The only exception will be educators and child care providers, who also can also get vaccinated starting Monday.

Last month, Nebraska Gov. Pete Ricketts also indicated the state would adopt a plan to move away from prioritizing vaccinating people with chronic illnesses. But Friday he said Nebraska would issue plans in March to give certain people, such as those on dialysis and those who have compromised immune systems, priority when the state finishes vaccinating those 65 and older.

Rhode Island has also set up an age-based plan, and the state estimates it will begin vaccinating people younger than 65 by age group starting in mid-March. But between vaccinating the group of residents who are 60 to 64 years old and those with ages ranging from 50 to 59, Rhode Island also will offer vaccines to people with certain chronic illnesses. The state expects to start vaccinating those in the 16-to-39 age group in June.

In addition, Indiana also has set up a largely age-based vaccine priority system for adults 60-64. It has plans to continue vaccinating by age but also include people with chronic conditions.

Cathy Wilcox, 59, of Stamford, Connecticut, made an appointment for Monday when the new eligibility kicks in. “I am really happy to be able to get it,” she said.

Wilcox, who wears a KN95 mask when working the front desk at an indoor tennis facility, expected she wouldn’t be eligible until April or later but is excited because she has been worried about her risk of getting covid-19. “What worries me about covid is you can have no symptoms but be a carrier and be fine or you can die or everything in between,” she said.

More than 40 states adopted plans to prioritize adults with certain chronic conditions, a strategy that generally uses the “honor system” for people to self-attest they have conditions ranging from a smoking history to asthma, according to KFF. (KHN is an editorially independent program of KFF.)

“There is no obvious right or wrong way to do it,” said Dr. Amesh Adalja, an infectious diseases expert with the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security in Baltimore. He said the goal of the vaccine program — at least initially — is to protect the most vulnerable so they don’t overwhelm hospital capacity. But it is difficult to determine who is most at risk.

A simpler age-based system could speed vaccination efforts that some say have been complicated in states with covid priority phases with numerous tiers based on job and health status, Adalja said. “There is a clear argument to make it as simple and seamless as possible,” he added.

The big advantage of giving vaccines out by age is it could reduce people from gaming the system (or lying that they have a health condition) since vaccinators can easily check a person’s age identification, said Dr. Richard Zimmerman, a University of Pittsburgh professor who works with its Center for Vaccine Research.

“It may stop some people from skipping the line,” he said.

States and the District of Columbia defend their systems that give early access to people with chronic illnesses, saying they are following CDC recommendations.

After it finishes vaccinating seniors, Maryland will include all adults 16 to 64 who are front-line workers and adults with certain health conditions. A spokesperson for the Maryland Health Department said vaccines should be in large-enough supply in a few months so there won’t be a need to prioritize by age.

Washington, D.C., has a similar strategy. “Age is not a good metric for disease severity nor disease progression,” the city’s health department said in a statement when asked why it plans to eventually give people ages 18 to 64 equal access to the vaccine.

Age also doesn’t not necessarily reflect overall risk, said Dr. Ana Núñez, an internist and vice -dean for diversity, equity and inclusion at the University of Minnesota School of Medicine. Housing, employment and other social determinants can raise a healthy person’s chance of getting the virus.

Indeed, experts said these factors help explain why people from Black, Hispanic and Native American backgrounds are dying at disproportionately high rates.

Distributing by age without targeting the most affected populations also gives preference to white residents, she said, because they outnumber racial and ethnic minority groups in many states.

“If you just do age,” Núñez said, “who are you preferentially immunizing?”

Michelle Cantu, who oversees infectious disease and immunization programs at the National Association of County and City Health Officials, said it’s important for jurisdictions to use data to determine who and how they immunize.

Multiple locations with large minority populations have contacted her in the past month about how an age-based system doesn’t work for them, she said. “I think there are a lot of critical considerations that states and local health departments have to consider,” she said.

Figuring out the best priority order for vaccines will be a short-term issue, as the number of vaccine doses is expected to rise exponentially by late April. But the question of vaccine hesitancy may then become a greater challenge, said. Dr. Sonja Rasmussen, a professor in the departments of pediatrics and epidemiology at the University of Florida.

“I have a concern we will soon get to a point where we have more vaccine than people who want to get it.”

Correction: This story was updated on March 1 at 11 a.m. ET to report that Indiana also has a vaccination plan that is based largely on eligibility by age. The state plan also notes, however, that people with chronic medical conditions may be included.