Covered California still faces major challenges in enrolling African-Americans and Latinos as the state’s health insurance exchange launches its third open enrollment period Sunday.

“We know we’ve come up short in who’s enrolled today,” Covered California Executive Director Peter Lee said at a recent media briefing on the exchange’s marketing and outreach plans. “Of those who are still uninsured, we want to make sure we reach them.”

About 2.4 percent of the exchange’s approximately 1.3 million enrollees are African-American, only about half of the blacks considered eligible for subsidies because of their income. Another 30 percent are Latino; 37 percent are considered eligible for subsidies, according to Covered California data.

In contrast, enrollment of whites and Asians has exceeded eligibility projections, meaning that Covered California was better able to reach those groups. The state’s enrollment data is not exact, because more than a quarter of enrollees decline to state their race.

While many more California Latinos and African-Americans have become insured since the passage of the Affordable Care Act, including through the state’s Medi-Cal expansion and employer-based insurance, Covered California’s experience echoes that of other states trying to ensure that their minority populations get the health coverage they need, said Larry Levitt, senior vice president at the Kaiser Family Foundation.

About 55 percent of the nation’s remaining 32.3 million uninsured under age 65 are people of color, including 34 percent who identify as Hispanic/Latino and 14 percent who identify as black, according to Kaiser Family Foundation data. (KHN is an editorially independent program of the foundation.)

In California, about 2.2 million Californians remain uninsured but are eligible for Medi-Cal or Covered California insurance plans, Lee said. They are more likely to be Latino and African-American, and younger and slightly more affluent than current enrollees, who may have qualified for subsidies or Medi-Cal, the state’s version of Medicaid.

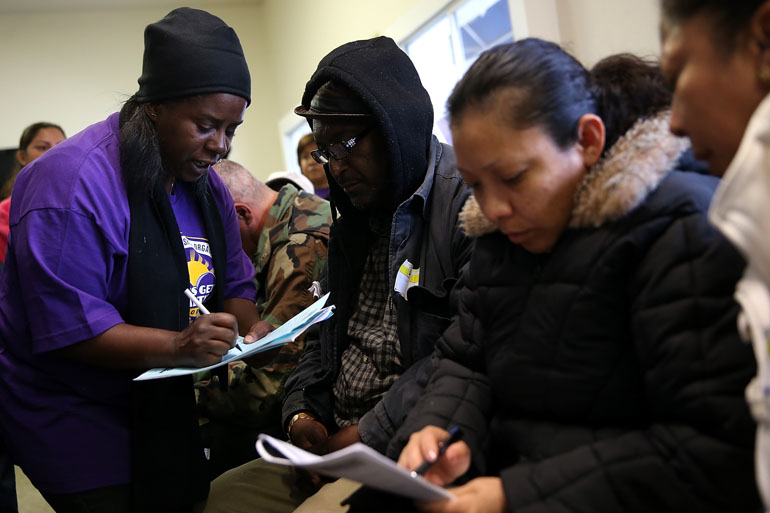

Covered California has earmarked about $50 million for marketing and another $13 million for navigators, trained counselors who help people learn about and sign up for coverage. The exchange was expected to unveil its new advertising campaign Friday, including ads specifically targeted to Latinos and African-Americans. Covered California’s open enrollment runs from Nov. 1 to Jan. 31, 2016.

Explanations for the disproportionately low enrollments of eligible African-Americans and Latinos vary. “We’ve got people who don’t trust the government,” said Dan Daniels, coastal area director of the NAACP California State Conference, who oversaw Affordable Care Act outreach in his region.

Daniels also cited attitudes among “young invincibles,” who are healthy enough to think they don’t need coverage and are willing to pay the mandatory penalty for not having health insurance. That penalty will rise in 2016 to $695 per person or 2.5 percent of income, whichever is higher.

Among some Latinos who are legal residents, there is fear that applying for health insurance through Covered California will jeopardize the immigration status of other family members, Levitt said.

And affordability remains a looming concern for higher-income people of color who may not be eligible for subsidies or Medi-Cal.

For example, Kemisha Roston, a 38-year-old contract lawyer from Riverside, said she makes too much money to qualify for those programs, but not enough to afford Covered California unsubsidized premiums – which top $300 per month — while she pays off student debt.

“I’m living check to check, because the market for attorneys is very saturated,” Roston said. “My health is pretty good right now, so I don’t need to go to the doctor. When I do, I go to free clinics or Planned Parenthood. I’m dismayed, because if something does happen and I don’t have health insurance, I could be wiped out.”

In addition, some community leaders and health advocates have criticized Covered California’s previous marketing and outreach efforts to both African-American and Latino communities as too generalized and impersonal. The exchange has spent more money on marketing and outreach than other exchanges, with less to show for it, said Hector De La Torre, executive director of the Transamerica Center for Health Studies.

“You have these challenges in these communities and it takes a lot more than a TV commercial to make them aware of what they need to do – you can’t do that in 30 seconds,” De La Torre said, referring to the need to educate people about the basic value of health insurance. “That’s where Covered California has not done as much as it could in reaching out to these folks. It’s a face-to-face communication effort that needs to take place.”

Charla Franklin, community outreach liaison for Healthy African American Families, an advocacy group in Los Angeles, said Covered California did well in reaching out to California’s black churches and community groups to get the word out. But the advertising campaign in her area was “so bland it was ridiculous,” she said. The exchange really needed to better inform people about specific community events and places where people could get in-person help with the complicated and time-consuming online enrollment process, she said.

Lee has told reporters recently that Covered California is stepping up its ground game and changing its messaging. Consumer surveys have shown that potential enrollees need more education on how subsidies can lower their out-of-pocket costs, he said. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services said it will pursue a similar strategy of publicizing financial help available to many people.

“We cannot take it as a given that Californians understand that health care is more affordable because subsidies are available,” he said. “We’ll be getting back to basics.”

The exchange is also expanding its direct outreach efforts, more than doubling the number of Covered California storefronts where people can get help to enroll to 500, Lee said. The exchange also plans door-to-door canvassing in communities with the highest remaining number of uninsured people, including Culver City, Inglewood, Riverside, Oakland and Richmond.

But while Lee promised “a more intense ground game,” he also cautioned against overly high expectations for the exchange’s third open enrollment season.

“We have millions of Californians who’ve adopted a culture of coping. They don’t understand they have subsidies available to them and are making do. It’s going to be years to change to a culture of coverage.”

The California Wellness Foundation supports KHN’s work with California ethnic media.