[UPDATED at 6:15 p.m. ET]

SACRAMENTO, Calif. — A proposal sailing through the California legislature that aims to stop people from getting harassed outside of vaccination sites is raising alarms among some First Amendment experts.

If it becomes law, SB 742 would make it punishable by up to six months in jail and/or a maximum fine of $1,000 to intimidate, threaten, harass or prevent people from getting a covid-19 — or any other — vaccine on their way to a vaccination site.

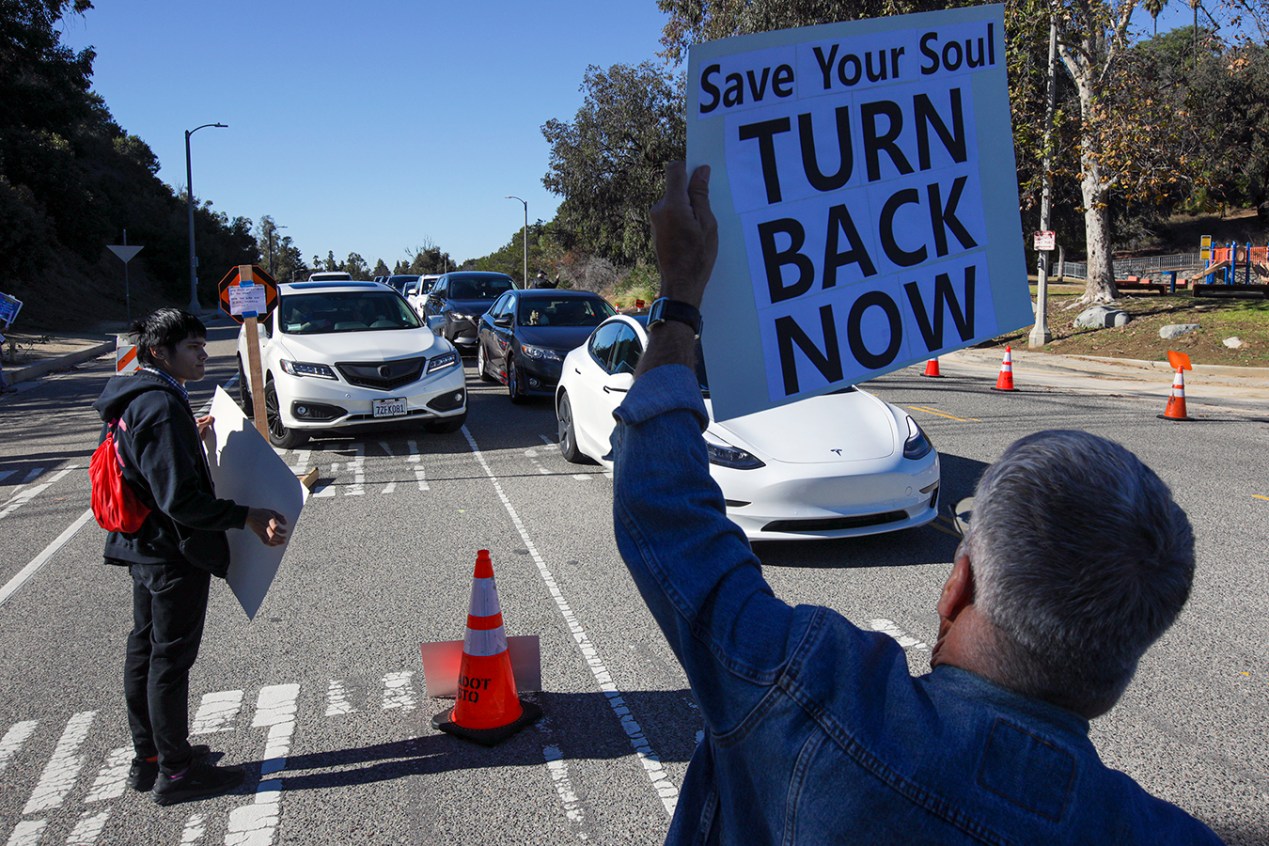

The measure was introduced after protesters briefly shut down a mass vaccination clinic at Los Angeles’ Dodger Stadium in January. Now that mass vaccination clinics have mostly folded up, lawmakers worry that vaccination sites with less security than Dodger Stadium — like pharmacies and mobile clinics in parks or fast-food parking lots — are vulnerable.

It’s a sign of how toxic the issue of vaccination has become in a state with a long history of intense and divisive vaccine wars.

State Sen. Richard Pan (D-Sacramento), a pediatrician who administers vaccines to his patients, wrote the bill. He has been the target of anti-vaccination harassment since writing and championing laws that made it harder for parents to refuse routine vaccines for their children by eliminating personal belief exemptions and tightening rules around medical ones.

He was shoved by someone who opposed the medical exemption bill in 2019, the same year in which an anti-vaccine protester threw menstrual blood onto the state Senate floor.

Pan was also among the lawmakers threatened at a committee hearing earlier this year.

Last month, Pan volunteered at a vaccination clinic at a Sacramento park that he said was disrupted by anti-vaccine protesters with a bullhorn who made it hard for medical personnel to converse with patients and answer their questions.

And while he said he can handle threats, ordinary citizens “shouldn’t have to run a gauntlet to get vaccinated.” That includes walking through a group likely made up of unvaccinated protesters and possibly getting exposed to covid to get protected, he said.

His measure prohibits obstructing, injuring, harassing, intimidating or interfering with people “in connection with any vaccination services.” The bill passed the state Senate with just four no votes and faces one more committee hurdle before it heads to the Assembly floor.

The bill defines harassment as getting within 30 feet of someone to hand them a leaflet, display a sign, participate in any kind of verbal protesting like singing or chanting, or conduct any education or counseling with that person.

Blocking someone or impeding them from getting a vaccine is an obvious problem, and it’s good that the proposal would try to stop that, said Glen Smith, litigation director for the First Amendment Coalition, a California-based nonprofit that promotes the First Amendment, which guarantees rights such as free speech and assembly. But he thinks the proposal goes too far with its definition of harassment.

“To say you can’t get within 30 feet of them just to hand them a pamphlet or ask them a question? That seems to be overkill for me,” Smith said.

It’s worse than overkill, said Eugene Volokh, a professor of First Amendment law at the UCLA School of Law.

“That law is clearly unconstitutional,” Volokh said.

He has two primary concerns with the proposal:

First, though it’s modeled on similar laws that create zones around abortion clinics to protect patients from harassment, this bill goes beyond what courts have upheld in the past, he said. In 2000, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld a Colorado law that created an 8-foot “bubble zone” around a person entering or exiting an abortion clinic, but in 2014 the high court struck down a Massachusetts law that created a 35-foot “buffer zone” around clinics.

A 30-foot zone around a person getting a vaccine is bigger than the court would allow, Volokh believes.

His second concern is that the bill specifically prohibits someone from leafletting or talking to someone only about vaccines.

That violates the First Amendment, Volokh said, because it targets certain content. Someone could hand out an anti-war or anti-fur leaflet and not run afoul of the law, he said.

“I think it’s pretty shocking that a state legislature would try to enact this kind of restriction on fully protected speech this way,” Volokh said.

The Right to Life League, which has opposed the measure from the start, advocated to get “in connection with vaccination services” added to the bill language.

Once the bill was amended to include that phrase, that limited “the negative impact of the bill on pro-life activities,” like anti-abortion sidewalk counseling outside Planned Parenthood clinics, which provide abortions and vaccines, Elisabeth Beall, media coordinator for the Right to Life League, wrote in a statement.

The group still believes the bill is unconstitutional.

Not all free speech advocates share Volokh’s interpretation of the bill. The American Civil Liberties Union said it has no issues with it as written.

“It’s not necessarily the case that the freedom to express our views is unrestricted,” said Kevin Baker, director of governmental relations at ACLU California Action. “They can be balanced with important governmental objectives” like letting people get vaccinated in peace.

Part of that objective is stopping disinformation about vaccines, which Pan said is the primary reason people are not getting the shots.

“Frankly, any gains we make to try to get more people vaccinated are going to be incremental because of disinformation,” Pan said. And when protesters show up claiming they’re there to educate patients, “they’re talking about disinformation.”

Joshua Coleman, co-founder of the group V is for Vaccine, which advocates for informed consent before vaccinations and says vaccines carry risk, said he brought the bullhorn to Pan’s clinic to “educate those coming to receive the vaccine on important facts they deserve to know” and object to Pan’s bill.

“The intent in attending Senator Pan’s vaccination clinic was to protest the censorship of important information and his egregious and erroneous attack on free speech,” he said via email.

Pan said his bill was “carefully crafted” to stop the “obstruction, harassment and intimidation” of people seeking vaccines, and is confident that it is well within the bounds of the First Amendment.

“There’s precedent for saying you can protest. This law doesn’t say you can’t protest. There’s certain rules around the protest,” Pan said. “Especially as we’re trying to deal with this pandemic, we need to do what we can to be sure people feel safe getting themselves vaccinated.”

This story was produced by KHN, which publishes California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation.

[Correction: This article was revised at 6:15 p.m. ET on Aug. 9, 2021, to correct the Right to Life League’s position on SB 742. A previous version of the story implied the group had changed its stance to support the bill, but it still opposes it.]