When America’s joint surgeons were challenged to come up with a list of unnecessary procedures in their field, their selections shared one thing: none significantly impacted their incomes.

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons discouraged patients with joint pain from taking two types of dietary supplements, wearing custom shoe inserts or overusing wrist splints after carpal tunnel surgery. The surgeons also condemned an infrequently performed procedure where doctors wash a pained knee joint with saline.

“They could have chosen many surgical procedures that are commonly done, where evidence has shown over the years that they don’t work or where they’re being done with no evidence,” said Dr. James Rickert, an assistant professor of orthopedic surgery at Indiana University. “They chose stuff of no material consequence that nobody really does.”

The medical profession has historically been reluctant to condemn unwarranted but often lucrative tests and treatments that can rack up costs to patients but not improve their health and can sometimes hurt them. But in 2012, medical specialty societies began publishing lists of at least five services that both doctors and patients should consider skeptically. So far, 54 specialty societies have each offered recommendations and distributed them to more than a half-million doctors.

Hospitals that have deployed the lists, including Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, report that the frequency of superfluous procedures has dropped. Consumer Reports, AARP and Univision are some of the influential organizations that have been part of a broad campaign to educate patients about the questionable items. Dr. Donald Berwick, a former head of Medicare, heralded the “Choosing Wisely” campaign as “a game-changer” because the “advice comes not from payers or politicos, but from pedigreed physician groups.”

Yet some of the largest medical associations selected rare services or ones that are done by practitioners in other fields and will not affect their earnings. “They were willing to throw someone else’s services into the arena, but not their own,” said Dr. Nancy Morden, a researcher at the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy & Clinical Practice in New Hampshire.

Some specialists did target their own money-makers. Gastroenterologists, radiologists and clinical pathologists all placed their own tests on their lists. The Society of General Internal Medicine recommended against the annual physical exam, a mainstay of American health care.

Other specialty groups said they did not include their own procedures where there are concerns of overuse, such as stents for heart patients and spine surgery, because the evidence is murky and the procedures are right for some patients. “What we did when we made up the list was to start with more straightforward situations and hopefully expand that later,” said Dr. F. Todd Wetzel, a member of the board of directors of the North American Spine Society.

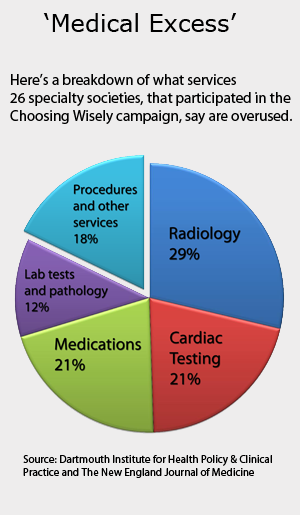

Those societies tended to focus on limiting testing that others do. In an article in the New England Journal of Medicine, Morden examined all the items on the first 26 Choosing Wisely lists. She found that 83 percent of the items targeted radiology, medications and cardiac and lab tests—not physician services.

Stenting Gets A Pass

The American College of Cardiology opted to list the use of cardiac testing in four circumstances. But the college did not tackle what studies suggest is the most frequent type of overtreatment in the field: inserting small mesh tubes called stents to prop open arteries of patients who are not suffering heart attacks, rather than first prescribing medicine or encouraging a healthier lifestyle. As many as one out of eight of these stent procedures should not have been performed, according to a study in Circulation, the journal of the American Heart Association. At hospitals where stenting was most overused, 59 percent of stents were inappropriate, the study found.

“Let’s face it, angioplasty and stenting is a big business, it’s highly profitable for hospitals, and it’s highly remunerative for physicians,” said Dr. William Boden, a New York cardiologist who oversaw the first large trials that found no advantage for stents for patients who are not in acute distress. “There’s a tremendous impetus to not rock the boat and not to call attention to the fact that we do too many procedures in stable patients for whom outcomes would be the same if not even better if treated medically.”

Dr. William Zoghbi, a Houston cardiologist who was president of the college when the list was announced in 2012, rejected the suggestion that stenting procedures should have been more broadly questioned, saying “the vast majority” of stents “are quite appropriate for the condition.” He said cautious choices for the initial list made sense because a campaign like Choosing Wisely is unfamiliar to doctors. “You have to walk before you run,” Zoghbi said.

The cardiologists did discourage one specific use of stenting, where doctors opening a clogged artery place additional stents in other places where screenings have spotted the starts of blockage. Dr. Vikas Saini, a Massachusetts cardiologist and president of the Lown Institute, which advocates for more restraint in treatments, said, “in 20 years of practice that’s not something I would have thought is standard and if people are still doing it, that’s a shame.”

Stents are a profit center for the group of cardiologists who perform procedures, often known as invasive cardiologists. They earned a median salary of $488,000, according to the Medical Group Management Association. Orthopedic surgeons do even better: half earned more than $538,000 in 2012, according to the MGMA’s income survey.

The orthopedic academy defended its Choosing Wisely selections, writing in a statement that “our recommendations are limited by the existing evidence regarding the effectiveness of various treatment options for musculoskeletal conditions, which we are seeking to improve.” It noted that its recommendation against the dietary supplements could save patients $750 million a year spent on these drugs.

The orthopedists’ selections did not impress critics. Rickert, the Indiana orthopedist, noted that discouraging dietary supplements affects revenue for health stores and other retail outlets, not surgeons. Both he and Morden said saline injections to treat knee pain are seldom done. Morden said when she searched 2011 Medicare billing records for the procedure, “I found zero claims.”

“That’s how pathetic that item is,” she said.

Dr. Augusto Sarmiento, a former president of the academy and retired chairman of orthopedics at the University of Miami Miller Medical School, said there were more significant overused procedures the academy omitted, including replacing hips and knees when the patient’s pain is minimal and can be managed with medicine.

In addition, Sarmiento said too many surgeons operate on simple fractured collarbones, inserting metal plates, rather than letting the injury heal with the help of a sling. “The abuse of surgery is due to the overwhelming control of the profession by the implant manufacturing companies,” he said.

Spinal Fusions Spared

The median compensation of a spine surgeon is more than $730,000, according to MGMA’s survey. It is unclear how many spine surgeons are still performing a procedure the North American Spine Society placed on its list: using bone growth material in spinal fusion in the neck. The Food and Drug Administration issued a safety alert against this in 2008, noting that the procedure had led to the swelling of neck tissue that compressed patients’ airways, making it hard to breathe or speak.

“I think the use for that purpose has already fallen off substantially,” said Dr. Richard Deyo, a professor at Oregon Health & Science University and spine researcher. “They’ve taken on the easy things.”

The only other procedure the society mentioned was spinal injections, but it was to expand, not restrict their work: They encouraged doctors to do their injections with the help of imaging, which would tack on another expense. The group also did not address spinal fusion, which has more than doubled in frequency between 1998 and 2008, faster than most procedures, one study showed. Other research found that patients with back pain were increasingly likely to get a physician referral, “presumably for consideration of treatments such as injections and surgery” while referrals for physical therapy stayed flat over a decade.

Wetzel, the spine society official and an orthopedic surgeon at Temple University Medical School in Philadelphia, said that since spinal fusion has been shown to be useful “under very specific circumstances,” the society “didn’t feel comfortable making any kind of blanket statement.”

The importance of which items are included is not just an academic debate, because where the lists have been actively embraced, the rate of those services has dropped. Last year, the Cedars-Sinai Health System in Los Angeles added 120 Choosing Wisely recommendations into its computerized patient records so that they would pop up on a screen whenever a clinician tried to authorize one.

“The alerts fire about 100 times a day,” said Dr. Scott Weingarten, Cedar-Sinai’s chief clinical transformation officer. For example, he said, there has been a decrease in the use of benzodiazepines and other sedative-hypnotics to treat the elderly, as they result in more falls, following a recommendation from the American Geriatrics Society for Choosing Wisely.

“We’ve got a bunch of other countries knocking on our door,” said Dr. Richard Baron, president of the ABIM Foundation, which solicited the Choosing Wisely lists from the specialties. “There’s a Choosing Wisely Canada. There are health systems using it, insurers are using it.”

Dr. John Santa, medical director for Consumer Reports, said reducing tests is a worthy goal because test results often prompt patients to get procedures. He cited electrocardiograms, which are used to measure the heart’s electrical activity to diagnose heart disease. “Some people would say, it’s a $50 test, it’s harmless,” Santa said. “The false positives you get from EKGs can cause significant downstream problems. You may think you may have just been brilliant in detecting some abnormality. That’s how stents get put in.”

In Annapolis, Md., the Anne Arundel Medical Center broadcasts “Choosing Wisely” lists on hospital television screens, places posters on the walls of doctors’ offices and discusses the lists in its magazine that it mails to county residents. The lists are also embedded as links in electronic patient records so physicians can easily review them.

Dr. Barry Meisenberg, an oncologist in charge of the hospital’s quality efforts, said the lists are helpful when he is trying to explain to disappointed patients why he is not ordering a particular test. “It does help that’s not just this guy’s opinion, it actually has the imprimatur of a society,” he said.