Jeanne d’Arc Kayembe, who came to Washington from Kinshasha, Congo, as a tourist, suffered pregnancy complications and was told to stay in bed until the baby was born. She struggled to oversee the medical care for her sick son while also trying to find a way to stay in the United States. Officials at Children’s National Medical Center helped her apply for asylum. (Susan Biddle/Washington Post)

For Jeanne d’Arc Kayembe, the trip to Washington in May 2007 was meant to be a month-long respite from an abusive boyfriend and a chance to visit relatives before going home to the Democratic Republic of the Congo to have her first child.

But searing abdominal pains sent Kayembe, who was six months pregnant, to Shady Grove Adventist Hospital. After relieving her pain, a doctor told her to stay in bed and not return to Kinshasa until after she had delivered her baby.

The Shady Grove emergency room was the entry point for Kayembe, who spoke almost no English and had little money, to a foreign medical system that was, by turns, both frightening and surprisingly welcoming.

Kayembe gave birth at Shady Grove to a very sick son, Don Emmanuel, who eventually got more than $1 million worth of care, mostly at Children’s National Medical Center. U.S. taxpayers and the hospitals footed the bill.

In some ways, Kayembe and her son are at the white-hot intersection of immigration and health care. But Kayembe’s case doesn’t fit neatly into those political and policy battles, which often focus on undocumented immigrants. An employee of Congo’s telecommunications agency, she came to the U.S. legally, on a tourist visa. And because her son was born here, he became a U.S. citizen and thus was entitled to Medicaid, like any poor child.

To Mark Krikorian, executive director of the Center for Immigration Studies, a Washington think tank that supports tighter immigration controls, Kayembe’s case suggests that rules for entering the United States ought to be toughened. He questions the wisdom of admitting a woman who was six months pregnant and from a country with a primitive health system. (Visa applicants are not asked whether they are pregnant.)

“The basic question when you’re looking at the intersection of health care and immigration is the selection of whom to admit,” he said. “Once you admit somebody, the game is up.” Lawmakers, he said, “need to be a little more demanding in this area.”

But Adam Gurvitch, a consultant to the National Immigration Law Center, which advocates for the rights of low-income immigrants, disagreed. He said that U.S. officials already have a screening process for visas that is highly subjective and rejects many more applicants from poor countries than from Western Europe or Japan. He added that “we would never accept such prohibitions for Americans” wanting to go overseas.

As the debate ensues, legal and undocumented immigrants continue to show up in emergency rooms, where hospitals are required by federal law to treat and stabilize them. In Kayembe’s case, medical staff helped in crucial ways that went far beyond health issues.

Alone — And Crushed

After Kayembe’s first visit to Shady Grove, she followed the doctor’s advice, staying at the Germantown home of her nephew, 23. Much of the time she was alone. When Kayembe, then 39, gave birth in August 2007, she was crushed to learn that her son had two heart defects and suffered from congenital developmental issues.

“I was happy when the baby was born, but then the happy left when the nurse told me he had a heart problem,” Kayembe said in an interview. “I said, ‘Why, my God?’ and I cried all day.”

The baby remained in the intensive care unit at Shady Grove for two weeks, but he needed specialized care, including a cardiac catheterization to repair a ventricular problem and a hole in his heart. Doctors decided the surgery should take place at Children’s after the baby grew a bit stronger.

Over the next several months, Don Emmanuel’s health deteriorated. He suffered from congestive heart failure, his breathing was labored and his heartbeat irregular. He was repeatedly hospitalized and once was flown by helicopter from Shady Grove to Children’s for emergency treatment.

In January 2008 doctors at Children’s successfully operated on the 5-month-old. But the baby had high blood pressure in the lungs, hypothyroidism and other problems that required in-hospital follow-up care.

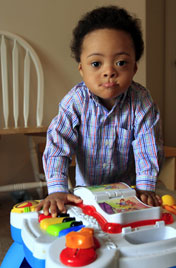

Don Emmanuel Kayembe no longer requires oxygen at night and doctors say his heart problems have improved markedly. (Susan Biddle/Washington Post)

The cost of the Shady Grove care was $32,000; most of that amount was covered by Don Emmanuel’s Medicaid, while Kayembe’s lesser charges were absorbed by the hospital as uncompensated care. Children’s officials say Medicaid eventually picked up a little less than half of the baby’s $1 million tab, with the hospital absorbing the rest.

Children’s is known as a place where legal and illegal immigrants, as well as American citizens with little money, can bring their children for top-notch care. In some cases, parents from other countries bring kids to the emergency room directly from the airport, hospital administrators say.

But that comes at a price. Children’s, like many other hospitals, doesn’t keep track of how much uncompensated care they provide to noncitizens, documented or undocumented, but they said it is significant. The hospital once spent $3 million treating an illegal immigrant child with leukemia, officials say.

The federal government helps subsidize uncompensated care by providing $11 billion through a Medicaid program that assists hospitals with a disproportionate number of low-income patients. But that doesn’t cover the entire need. Hospitals often turn to charities for help or pass the cost of uncompensated care along in higher prices to patients who do have insurance.

Out Of Options

Kayembe, struggling to oversee her son’s care, found that the people treating Don Emmanuel began to look after her, too.

Facing the expiration of the standard six-month tourist visa, Kayembe was terrified that she would be forced to return to Congo without her son. But just weeks before her visa was set to expire, social workers and doctors at Children’s wrote to the Department of Homeland Security’s Bureau of Citizenship and Immigration Services, explaining that she needed to stay in the country with her child while he received treatment. The agency granted an extension for another six months.

A social worker at Children’s, believing Kayembe might be eligible for asylum because she said she’d been abused by her boyfriend in Congo, e-mailed the Center for Applied Legal Studies at Georgetown University Law Center, requesting pro bono assistance for Kayembe.

Liz Keyes, a French-speaking attorney with Women Empowered Against Violence, a Washington nonprofit organization, decided to take the case.

Even Keyes, an experienced immigration lawyer, was surprised that the hospital had gone to such lengths to find legal help for Kayembe.

“I’ve never seen anything like it,” said Keyes. “I think what was driving it was this child, who was doing well but couldn’t do well if he was taken overseas or if his mother was distracted by overstaying her visa. They had to take care of mom’s immigration issues.”

There was little time to spare. Keyes tracked down family members and a priest in Congo who could provide affidavits about the alleged abuse, which was linked to ethnic discrimination. They said that Kayembe’s boyfriend, who was from a different Congolese ethnic group, had not wanted her to have a “mixed-blood” son. He had pressed her to have an abortion and made threatening comments about the child.

Kayembe, meanwhile, was distraught about the baby’s medical problems. “She would cry,” said Deneen Heath, the cardiologist at Children’s who treated the baby for congestive heart failure and other complications. “She never thought she would have a child with all these problems.”

Using her rusty French, Heath gleaned that Kayembe was having trouble getting back and forth from Germantown, so she set up a cot in the baby’s room and got permission for Kayembe to eat for free in the hospital cafeteria while Don Emmanuel received treatment.

In June 2008, Kayembe received asylum status, which Gurvitch of the National Immigration Law Center called “quite exceptional.” He said that her son’s U.S. citizenship didn’t confer any rights on his mother.

Today Kayembe is learning English and looking for a job while receiving aid from groups that help people who have been granted asylum. Her son is a smiling, chatty toddler. He no longer requires oxygen at night, and doctors say his heart problems have improved markedly.

Kayembe today recalls the kindness of the doctors and social workers. “I was so surprised because I never imagined somebody would help me like that,” she said through an interpreter. “They gave me so much.”