Psychiatric hospitalizations of Latino children and young adults in California are rising dramatically — at a much faster pace than among their white and black peers, according to state data.

After participating in the mental health program at Life Academy of Health and Bioscience, Nubia Flores Miranda, 18, decided to major in psychology at San Francisco State University. (Heidi de Marco/KHN)

While mental health hospitalizations of young people of all ethnicities have climbed in recent years, Latino rates stand out. Among those 21 and younger, they shot up 86 percent, to 17,813, between 2007 and 2014, according to the Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development. That’s compared with a 21 percent increase among whites and 35 percent among African Americans.

No one knows for certain what’s driving the trend. Policymakers and Latino community leaders offer varying and sometimes contradictory explanations. Some say the numbers reflect a lack of culturally and linguistically appropriate mental health services for Latinos and a pervasive stigma that prevents many from seeking help before a crisis hits.

“Often, they wait until they are falling apart,” said Dr. Sergio Aguilar-Gaxiola, a professor at the University of California, Davis Medical School and director of the university’s Center for Reducing Health Disparities.

Others blame stress from the recent recession, family disintegration and an influx of traumatized children fleeing poverty and violence in Central America.

Still others suggest the trend might actually be positive, reflecting an increasing willingness among Latino parents to seek treatment for themselves and their children, at least when they are in crisis.

Among Latino adults, psychiatric hospitalizations rose 38 percent during the same period. Similar hospitalizations of black adults increased 21 percent, while hospitalizations of white adults remained flat.

Margarita Rocha, the executive director of the nonprofit Centro la Familia in Fresno, said mental health issues are starting to be discussed more publicly in the Latino community.

“That’s helping people to come forward,” she said.

Miranda works part-time at Family Paths, a counseling and mental health organization in Oakland, California, in January 2016. She said she became interested in a career in mental health after she started experiencing depression and anxiety her freshman year in high school. (Heidi de Marco/KHN)

Ken Berrick, CEO of the Seneca Family of Agencies, which serves children with emotional disturbances in a dozen counties, agreed. Because more Latinos are now getting mental health services, children are more likely to be identified as requiring hospitalization, he said.

“I know for a fact that access to service is better now,” said Berrick, whose operation has a crisis stabilization unit in Alameda County, Calif.

Kids’ psychiatric hospitalizations overall rose nearly 45 percent between 2007 and 2014, regardless of ethnicity, a pattern experts attribute to various factors including a shortage of intensive outpatient and in-home services, schools’ struggles to pay for mental health services through special education and a decline in group home placements.

“Those kids have to be treated somewhere,” said Dawan Utecht, Fresno County’s mental health director, of the move to keep kids out of group homes.

“If they don’t get those services in a community setting, they’re going to go into crisis.”

The rise among Latino youths is remarkable in part because hospitalization rates for that population historically have been relatively low.

Latino children remain much less likely to receive mental health treatment through Medi-Cal, the state and federal coverage program for poor and disabled residents. Between 2010 and 2014, less than 4 percent of Latino children received specialty mental health services through the traditional Medi-Cal program. That’s compared with 7 percent of eligible black and white children, according to state data. The numbers don’t include those enrolled in managed care.

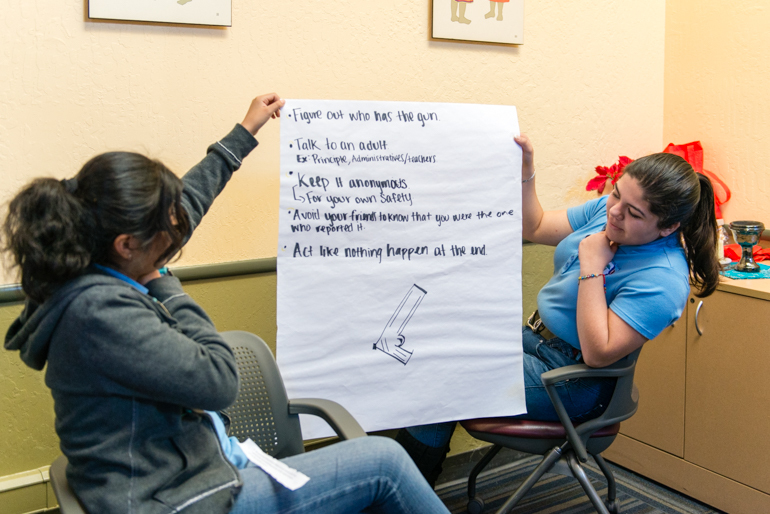

Eric Waters, coordinator for the behavioral health program at the Life Academy High School leads a discussion with Fernanda May, 17, and Graciela Perez, 17, at La Clínica de la Raza in Oakland, California, which provides training in first aid and places students in internships with mental health organizations. (Heidi de Marco/KHN)

(Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders seek treatment at a rate even lower than Latinos. Although hospitalizations are also increasing rapidly among that population, the raw numbers remain relatively small.)

Leslie Preston, the behavioral health director of La Clínica de La Raza, in East Oakland, says that the shortage of bilingual, bicultural mental health workers limits Latino kids’ access to preventive care, which could lead to crises later on.

“Everybody’s trying to hire the Spanish-speaking clinicians,” she said. “There’s just not enough clinicians to meet that demand.”

Access to care can be even harder for recent immigrants. Spanish-speaking children who have been referred for a special education assessment, which can help them become eligible for mental health services, sometimes wait months or years before someone tests them, she said.

“The families don’t know the system,” she added. “They don’t know their rights.”

Other clinicians point to relatively low health insurance coverage among Latinos, particularly those without legal status, and a cultural resistance to acknowledging mental illness.

Dr. Alok Banga, medical director at Sierra Vista Hospital in Sacramento, said some immigrant parents he encounters don’t believe in mental illness and have not grasped the urgency of their children’s depression and past suicide attempts. Many are working two or three jobs, he said. Some are undocumented immigrants afraid of coming to the hospital or having any interaction with Child Protective Services.

But the biggest problem, from his perspective, is the shortage of child psychiatrists and outpatient services to serve this population.

“The default course for treatment falls on institutions: hospitals, jails and prisons,” he said.

Jeff Rackmil, director of the children’s system of care in Alameda County, said sheer population growth — particularly, an increase in Latino children insured under Medi-Cal — may also be part of the explanation for the rise in hospitalizations.

Yet the state’s Latino population aged 24 and under increased less than 8 percent between 2007 and 2014, which doesn’t nearly explain an 86 percent increase in hospitalizations.

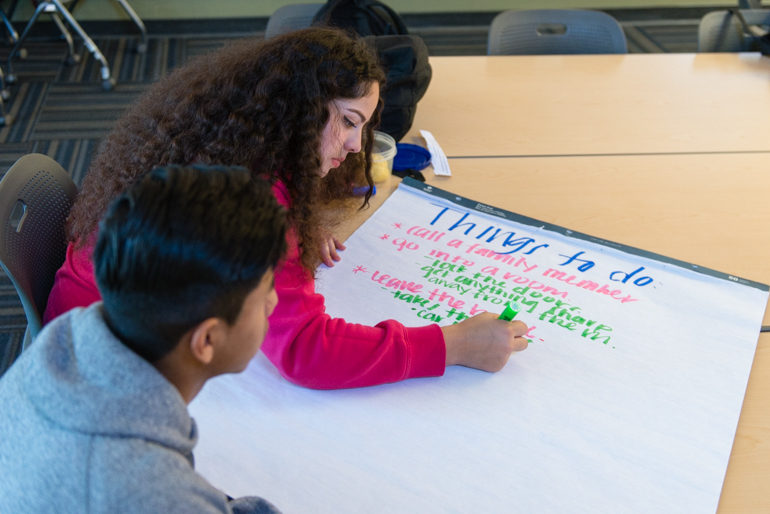

Elizabeth Ochoa, 17, and Victor Ramirez, 17, work on an assignment during their behavioral health training. The East Oakland students walk to the center from the nearby high school a few times a month. (Heidi de Marco/KHN)

Some California communities are working to bring more Latino children into care and to reduce the stigma associated with mental illness.

At Life Academy of Health and Bioscience, a small, mostly Latino high school in East Oakland, students grow up amid pervasive violence and poverty. “We’re just told to hold things in,” said 17-year-old Hilda Chavez, a senior.

Students often don’t seek help because they fear discussing mental health problems will earn them a label of “crazy,” Chavez said.

Last year, the school, in conjunction with the Oakland-based La Clínica de La Raza, started a program to interest students in careers in mental health care. The program provides training in “first aid” instruction to help people in crisis, and places students in internships with mental health organizations.

Nubia Flores Miranda, 18, participated in the program last year and now is majoring in psychology at San Francisco State University. Miranda said she became interested in a career in mental health after she experienced depression and anxiety during her freshman year at Life Academy.

Seeing a school counselor “changed my life around,” she said.

But she saw that her peers were wary of seeking help from counselors at the school, most of whom were white and lived in wealthier, safer neighborhoods. Once, when a classmate started acting out at school, Miranda suggested she talk to someone.

“She told me she didn’t feel like she could trust the person — they wouldn’t understand where she was coming from,” she said.

Graciela Perez, 17, and Nayely Espinoza, 17, hold up their group assignment during a class presentation. The students are preparing for their mental health internships by discussing solutions to potential scenarios, such as gun violence, suicide and depression. (Heidi de Marco/KHN)

The shortage of services is especially evident in the Central Valley, where many agricultural workers are Latino. Juan Garcia, an emeritus professor at California State University, Fresno, who founded a counseling center in the city, says the drought and economic downturn have exacerbated depression, anxiety, substance abuse and psychotic breaks among Latinos of all ages.

“The services to this population lag decades behind where they should be,” he said.

In Fresno County, psychiatric hospitalizations of Latino youth more than tripled, to 432, between 2007 and 2014. Hospitalizations of their white and black peers about doubled.

Liliana Quintero Robles, a marriage and family therapy intern in rural Kings County, also in the state’s Central Valley, said she sees children whose mental health issues go untreated for so long that they end up cutting themselves and abusing alcohol, marijuana, crystal meth and OxyContin.

“There’s some really, really deep-rooted suffering,” she said.

Out in the unincorporated agricultural community of Five Points, about 45 minutes from Fresno, almost all of the students at Westside Elementary School are low-income Latinos. When principal Baldo Hernandez started there in 1981, he’d see maybe one child a year with a mental health issue. These days, he sees 15 to 30, he said.

He blames dry wells and barren fields, at least in part.

“I’ve had parents crying at school, begging me to find them a home, begging me to find them a job,” he said.

In some parts of the Valley and other places, the closest hospitals that accept children in psychiatric crises are hours away. Children can be stuck in emergency room hallways for days, waiting for a hospital bed.

“It makes for a very traumatized experience for both families and children,” said Shannyn McDonald, the chief of the Stanislaus County behavioral health department’s children’s system of care.

Recently, the county expanded its promotora program, which enlists members of the Latino community to talk to their peers about mental health.

In the small town of Oakdale, a slim, energetic 51-year-old promotora named Rossy Gomar spends 60 to 70 hours a week serving as cheerleader, educator and sounding board for many of the Latino women and children in the town.

Hilda Chavez, 17, at La Clinica de la Raza, says students at her high school don’t really discuss mental health problems. Chavez says participating in the program has made her consider a career in behavioral health. (Heidi de Marco/KHN)

Gomar’s office in the Oakdale Family Support Network Resource Center is cluttered with open boxes of diapers and donated children’s toys and clothing.

“Look at my office,” she laughs. “We don’t fit.”

Gomar says many of the women she works with don’t recognize that they are depressed or abused. Children see their parents’ problems and don’t know where to turn for help.

“There are many young people who don’t have any hope,” she said.

But little by little, she has seen some good results.

One 17-year-old client is a student at Oakdale High School. The girl, whose name is being withheld to protect her privacy, said that earlier this year, problems at school and a break-up with her boyfriend had her struggling to get out of bed each morning. She began drinking, using drugs and thinking about suicide. She was scared to talk to her parents, she said, and kept everything inside.

One day, she walked into Gomar’s office and started crying.

“She told me ‘Everything is ok. We want you here,’” the girl said. “When I was talking with her, I felt so much better.”

The California Wellness Foundation supports KHN’s work with California ethnic media.

This story was produced by Kaiser Health News, which publishes California Healthline, a service of the California Health Care Foundation.