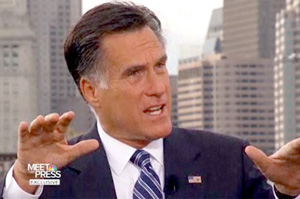

On Sunday, GOP presidential nominee Mitt Romney, appearing on NBC’s Meet the Press, said he would keep the popular provision in President Barack Obama’s health law that “makes sure those with pre-existing conditions can get coverage.”

And on ABC’s This Week with George Stephanopoulus, Paul Ryan appeared to back a lesser-known part of the law called “maintenance of effort” that prohibits states from making it harder for people to get covered by Medicaid, the state-federal health program for the poor, until 2014.

Both statements seemed to signal dramatic shifts in position for the Republican presidential ticket. But campaign officials later insisted the men hadn’t said anything they hadn’t said before.

On pre-existing conditions, campaign officials said later Sunday that Romney supports coverage for people with pre-existing conditions, but only for those who have had continuous coverage — a position Romney has had for months. That helps people who change jobs, but leaves out those with a gap in coverage. The Commonwealth Fund found that about 89 million Americans between 2004 and 2007 had at least a one-month gap of coverage.

A Romney official said that such people would be taken care of by state high-risk insurance pools.

In contrast, the federal health law starting in 2014 blocks insurers from denying coverage for pre-existing conditions for everyone. The provision is already in effect for children.

Since 1996, a federal law has protected people from being denied coverage for pre-existing conditions if they continually have coverage. The downside of that law is there is no limit on what insurers can charge. Under the federal health law, in 2014, insurers won’t be able to charge higher rates based on a person’s health status.

On the “maintenance of effort” provision, which was first included in the federal stimulus package in 2009, then continued by the 2010 health law, campaign officials clarified that despite Ryan’s comment, he is still in favor of killing the requirement because it inhibits state flexibility with Medicaid.

Ryan favors giving states block grants so they have broader power over the program. Stephanopoulus noted that the Urban Institute has estimated that between 14 million and 27 million fewer people will be covered under Medicaid block grants.

“I won’t get into the details, but with maintenance of effort requirements, which is what we’ve done in the past, they still have to serve this population,” Ryan said in the television interview.

Joe Antos, an economist with the conservative American Enterprise Institute, said he thinks Ryan meant to say that even if Medicaid became a block grant, states would have to continue serving those eligible for the program.

To receive guaranteed federal funding, states today must cover certain “mandatory” populations. These include children under age 6 with family income below 133 percent of the federal poverty line; children ages 6 to 18 with income below the poverty line; pregnant women with income below 133 percent of the poverty line; and most seniors and persons with disabilities who receive cash assistance through the Supplemental Security Income program.