As controversy about the pricing of EpiPens reverberates from Capitol Hill to school districts across the country, one recurring complaint from consumers is that the high cost is magnified because the drug expires quickly, forcing users to regularly bear the cost of replacing the medicine that saves lives in the event of a severe allergic reaction.

So what exactly determines its longevity? It turns out storage and distribution can play as important a role in the drug’s shelf life as the chemical compounds.

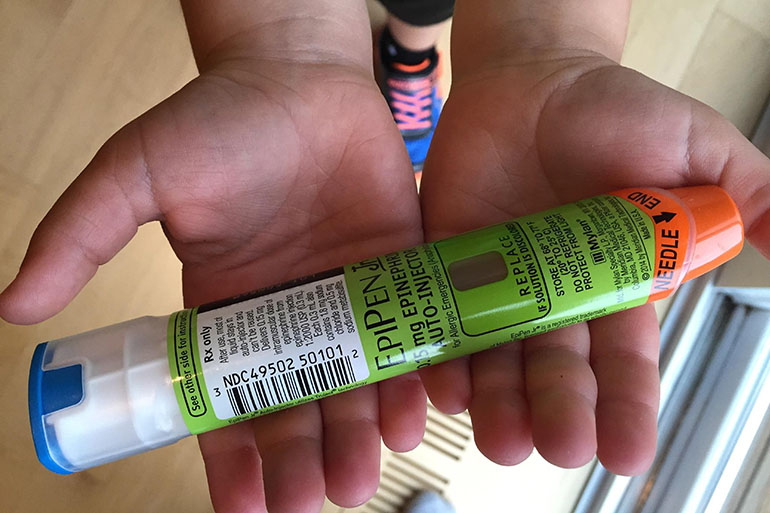

The EpiPen works by injecting into the body the drug epinephrine. That causes a series of physiological changes, including tightening blood vessels and opening airways.

Epinephrine is a generic medication and not very costly, but the drug maker Mylan has a patent on the design of the auto injector that is the key element of the EpiPen. That injector allows users to administer the medication more quickly than other options on the market. Under that patent, the company has progressively raised the cost of the drug since 2007 to about $600 for a pack of two today.

Since the medicine generally expires every year, the cost to replace EpiPens adds up fairly quickly, especially for consumers who do not have insurance or have high-deductible plans in which they must spend money out of pocket before the coverage kicks in.

“This is just a lifesaving medicine,” said Robert Glatter, an emergency room physician at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York. “You can’t let it expire.”

Environment plays a role the in the EpiPen’s lifespan. The medicine can be stored in areas fluctuating between 59 and 86 degrees, but it should not be exposed to extreme heat or cold. Mylan also advises users to protect the drug from light and not store it in a glove compartment.

According to Julie Knell, director of specialty communications at Mylan, the EpiPen expires every 12 to 18 months, but that period includes the time it takes to distribute the product and reach the patient’s hands.

Glatter said that is similar to the time that hospitals keep vials of epinephrine in stock, too.

Aside from the active ingredient, the EpiPen solution also contains fillers needed to help stabilize the drug. These compounds also break down over time, affecting the drug’s potency. Glatter said EpiPen users should look out for cloudiness or small pieces of matter in the liquid, as that indicates degradation.

Still, he pointed out that a study in 2000 found EpiPens can remain without apparent signs of deterioration for up to 90 months — seven and a half years — after the expiration date.

While he strongly discourages patients from allowing their EpiPens to expire, Glatter said using an expired one is better than none at all.

“They’re willing to take a chance, unfortunately,” he said.

Glatter said he’s seen a rise in people holding onto expired EpiPens because they cannot afford a new dose. And according on FDA standards, no other drug on the market is as effective.

Despite its dominance, consumers can purchase a cheaper alternative that contains the same medication: Adrenaclick’s generic option. That product lasts 18 months — the maximum length of time for the EpiPen — and can withstand the same temperatures as its competitor. Both the generic and EpiPen auto-injectors are designed with a viewing window to check the solution for cloudiness and particle matter.

Unlike the EpiPen, the generic auto-injector requires the user to remove an endcap before injecting the epinephrine. The alternative also stands out from its brand name competitor with its price tag: $395 for a two-pack.

Under intense scrutiny, Mylan announced several initiatives to reduce the cost of EpiPens for its users. Among them is the release of their own generic version, which, according to the company’s website, will be identical to their brand name drug at half the cost. In addition, the manufacturer will provide a direct-ship option, which allows consumers to buy the product directly from the company.

Mylan’s announcement drew sharp criticism last week at a hearing of the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee, with many members claiming the company would profit more from the generic drug than the brand name drug because it cut costs by eliminating the distributor. Mylan CEO Heather Bresch adamantly denied the accusations.

In addition, Bresch also announced the company is “day’s away” from submitting a proposal to the FDA for an EpiPen that expires every 24 months, double the shelf life of the current product.

KHN’s coverage of prescription drug development, costs and pricing is supported in part by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation.